Matthew L.C. Boyle

Abstract

Although Gioachino Rossini’s Figaro is one of opera’s most beloved characters, little analytical work has been dedicated to him or his music. This essay elaborates on aspects of Figaro’s character through two analytical vignettes. These vignettes add texture to Figaro’s status as a lower-class comic character and highlight his cunning and volatile temperament. The first vignette examines Figaro’s aria “Largo al factotum” as a comic patter aria inflected by a frantic tarantella topic. The second vignette contextualizes the historical musical resonances of Figaro’s parlante vocal texture in the tempo di mezzo passage of the duet “All’idea di quel metallo.” I propose that Figaro’s parlante mimics the cries of street vendors and depicts him as a crude and cunning outsider.

View PDF

Return to Volume 38

Keywords and Phrases: Rossini, Figaro, parlante, tarantella, topic theory, social class, Southern Italy

Introduction

Although Gioachino Rossini’s Figaro is one of opera’s most beloved characters, little analytical work has been dedicated to him or his music. Most interpretations of Rossini’s Figaro have been grounded either in close readings of the opera’s libretto or in the historical contextualization of particular performances. In many studies, musical analysis tends to focus on relatively simple compositional or performative elements. Paul Robinson (1985), for instance, focused on Figaro’s superficiality, proclaiming him to be pure ego: musical interest is mainly found in how a baritone “copes with [“Largo al factotum’s”] several high G’s” or “whether the singer [will attempt] a high A” (28). In other studies, close analysis only occasionally crops up, often in support of interpretive conclusions primarily drawn from the libretto. Some even view Figaro’s aria as a form of absolute music; for example, Janet Johnson (2004) claimed that in “Largo al factotum,” “Figaro’s words comment on his song, not the other way around” (169).

Figaro’s beloved stature, yet meagre placement, within analytical literature might stem from various causes. For example, the tile Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville) implies that Figaro, the barber, would the central character, yet he serves a secondary role within the opera’s plot. Instead, the opera’s original title of Almaviva more accurately reflects the Count’s centrality to the comic narrative and music; however, this is not to say that Figaro is inconsequential.1 Even though he is not the central romantic character of the comedic plot, he, like Don Alfonso from Mozart’s Così fan tutte, is able to see and wield the conventions of operatic composition to influence the world of the drama.2 Furthermore, like Don Alfonso, Figaro is an enigmatic character who resists simple categorization within the conventional terms of opera. Is he comic or serious; lower-class or bourgeois; central or peripheral; Spanish, French, or Italian?

For example, although Figaro is ostensibly a Spanish character (he is, after all, a barber in Andalusian Seville), he was often depicted with flexible national traits. The creator of the Figaro character, the French playwright Pierre-Augustin Beaumarchais, used him in Le Barbier de Séville (1773) as a mouthpiece for his own commentary on Parisian social and political developments (Coward 2003, xv–xx). Yet even with a French voice, Figaro is presented in Spanish garb, first appearing on stage “as a Spanish dandy” toting a Spanish guitar (3). Giovanni Paisiello’s operatic representation of Figaro in Il barbiere di Siviglia (1782) similarly gives him a cosmopolitan voice with his comic musical style neutrally reflecting the conventions of the pan-European galant. Paisiello, like Beaumarchis, also called attention to Figaro’s Spanish nationality primarily through secondary features like costumes, dramatic situations, and poetry—such as the listing of Spanish regions in the first act aria “Scorsi già molti paesi”—and not through his musical vocabulary.3 Mozart’s presentation of Figaro in Le Nozze di Figaro (1786), in contrast, foregrounds his Spanish origins musically in several important moments, most notably in the fandango scene that concludes the third act (Link 2008).

Unlike his predecessors, Rossini’s musical characterization of Figaro eschews overt Spanish references and, in his two most prominent musical numbers, even the neutral tone of a comic bass.4 Instead, Rossini’s music for Figaro alludes to musical topics associated with lower class Southern Italians. These topics, which include an imitation of a tarantella dance and a street vendor’s cries, were evocative of Neapolitan rather than Andalusian soundscapes. In particular, they recall well-established cultural codes from the nineteenth century that framed perceptions of Southern Italians. Poor Southern Italians, especially those from the Kingdom of Naples, were often a focus of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century grand tour travelogues and were discussed by both Northern Italian and Northern European writers in stereotyped, classed, and racialized terms. As a result, these styles had the potential to signify both place and class. Rossini’s musical portrait of Figaro consequently dresses him in unusual sonic garb: in his two most prominent operatic numbers, he is musically presented through a topical language evocative of Southern Italy’s urban poverty, suggesting a connection to comedic characters from the lowest of social rungs.5 Within this historic context, these musical allusions enrich Figaro’s enigmatic status and hold interpretive consequences for both performance and close readings of the opera.

This analytical essay explores Rossini’s musical depiction of Figaro. It begins with a discussion of early modern cultural codes concerning lower-status Southern Italians, detailing conceptions of Southern Italian voices and perceived volatile temperament. It then analyzes two first act passages sung by Figaro, which show how these codes were sonically manifested in nineteenth-century contexts. The first analysis finds Figaro’s breathtaking aria “Largo al factotum” to be evocative of the Southern Italian tarantella and the frantic impulsiveness that the dance connotes. The second analysis contextualizes the unusual style of Figaro’s parlante vocal texture in the tempo di mezzo passage of the duet “All’idea di quel metallo.” Figaro’s parlante mimics the cries of street vendors and depicts him as a hawker akin to a Neapolitan lazzarone.

Ultimately, the mode of analysis used in this essay is based on developing sensitivities to historical soundscapes and their encoded social meanings. This kind of analytical sensitivity can reveal potential avenues for performance, both in terms of musical execution and physical gesture. Indebted to Ratner (1980) and especially Allanbrook (1983), the analyses developed in this essay are concerned with how the gestural language of musical topics were used to communicate information about class and status in operatic contexts.

1. Cultural Codes and the Urban Soundscape of the Mezzogiorno

Rossini’s musical depiction of Figaro in Il barbiere di Siviglia, especially in the first act, sonically evokes images of poor Neapolitans through topical allusions to Southern Italian music. Southern Italy, a region commonly referred to as the Mezzogiorno, encompasses the southern half of the Italian peninsula and the island of Sicily, largely sharing the former borders of the Kingdom of Naples and the Kingdom of Sicily. The Mezzogiorno region and its inhabitants were objects of voyeuristic fascination for Northern Europeans and Northern Italians. Naples, in particular, was a focal point, since it stood at the southernmost point for many Grand Tour journeys. The city’s large port, grand opera house (the San Carlo), warm climate, ancient ruins (Pompeii lying south of the city), and a towering volcano (Vesuvius) marked it as a unique European landscape. More generally, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries Northern Europeans and even northern Italians understood Southern Europe—especially Neapolitan-controlled Southern Italy—as a liminal zone where European, African, and Asian cultures converged (Moe 2002, 49–50).

Stereotypes of the southern Mezzogiorno region of Italy were partially rooted in perceptions of its landscape. Outsiders described the Italian south as a wild territory, stuck in the past, filled with untamed nature, ancient ruins, poverty, poor governance, and volatile peoples. On the geographic and cultural frontier of Europe, its land was seen as alien by many outsiders. In 1808, for instance, a French bureaucrat wrote in a travelogue that “Europe ends at Naples…Calabria, Sicily, all the rest belongs to Africa” (Moe 2002, 37), and Jesuits in the sixteenth century referred to Calabria and Sicily as “the Indies” of Europe (Moe 2002, 37, 50). The Italian South’s landscape was seen as different through recuring images of its fertile soil, mild climate, and the volcanoes of Vesuvius and Etna (43). In souvenir art of Naples this landscape was emphasized as seen in the color lithograph of Figure 1, which presents a distant erupting Vesuvius looming over the Gulf of Naples. This space was primal, belonging more to a primitive past, set outside of time, than to a modern present (37–38).

Grand Tourists and Northern Italian outsiders conceptualized the people who populated this land as similarly alien through a chauvinistic lens. The climate and landscape were problematically understood as shaping the temperaments of the people who lived there. Southern Italians were ascribed a base, impulsive, and emotional temperament by outsiders.6 For instance, in the eighteenth century, the Baron Hermann von Riedesel described Sicilians as “restless and impatient [who], with their great degree of vivacity, often cause the most violent actions; they are therefore remarkable above all other nations for the violence of their jealously and vindictive temper” (Moe 2002, 59). More generally, those from the Italian South were “characterized by that effeminacy, voluptuousness, and cunning, which is found to increase in more southernly countries” (59).

These accounts of Southern Italians were often paired with commentary on the pervasive poverty in the region. Casanova commented that “I saw only poverty” after a sojourn to the Calabrian city of Cosenza (Moe 2002, 47). Charles de Brosses in his 1739–1740 letters from Italy described the inhabitants of Naples as “the most abominable rabble and loathsome vermin that ever infested the earth” (61). De Brosses and Casanova likely were describing a Neapolitan class of beggars known as the lazzaroni [scoundrels] who were often objects of fascination for Northern Europeans and those who traveled to Naples on the Grand Tour.7 This class of people was seen as consisting of societal outcasts. In part, this is reflected in the term’s etymology: the root of lazzarone, lazzaro, is an archaic term for a leper. Grand Tourists would have encountered them as beggars in the public spaces of the city, as porters, and as guides to sites nearby like Vesuvius and Pompeii. The begging class of lazzaroni were of interest because they intersected with early-nineteenth-century discursive traditions concerning the supposed unique qualities of the Mezzogiorno’s climate and culture. Within this cultural landscape, the begging class of the lazzaroni could be conflated with the throngs of street vendors that were also found in Naples’s busiest streets and public squares.

The appearance, sounds, and character of impoverished Neapolitans and Neapolitan street hawkers fascinated Grand Tourists. However, Neapolitans and other Southern Italians from the Mezzogiorno were not passive bystanders in this discursive environment. They sought to shape, correct, and exploit outsider perceptions of themselves and the region. As a result, Neapolitans created and sold souvenirs for both Grand Tourists and locals that presented stylized scenes of Neapolitan street life.8

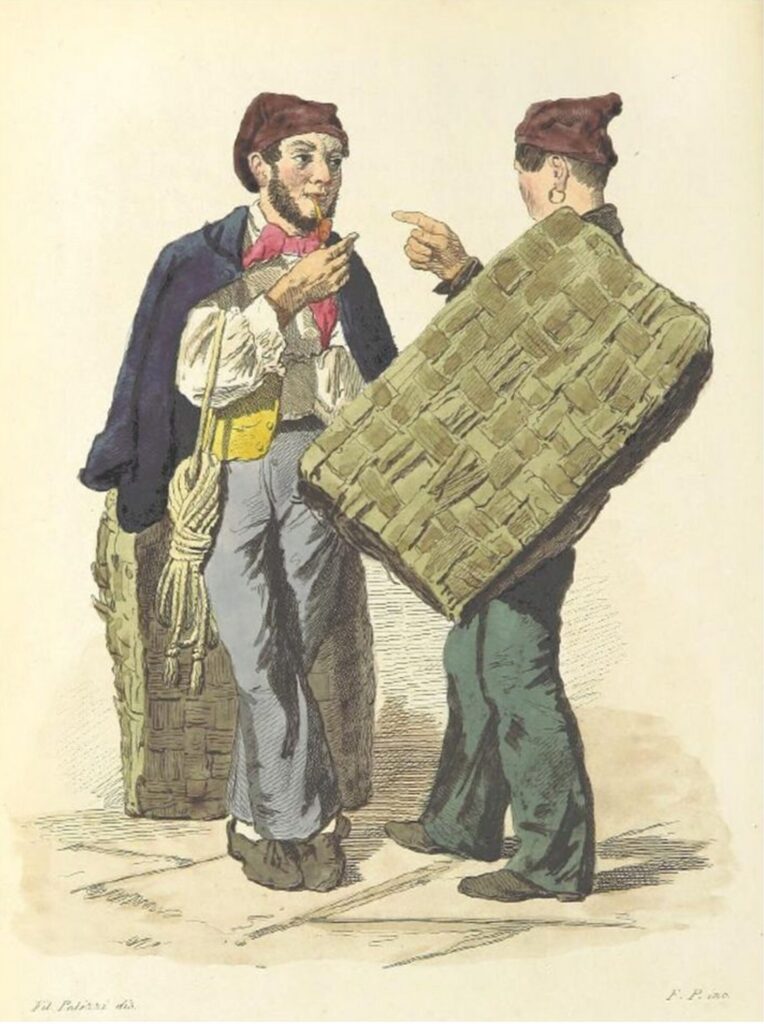

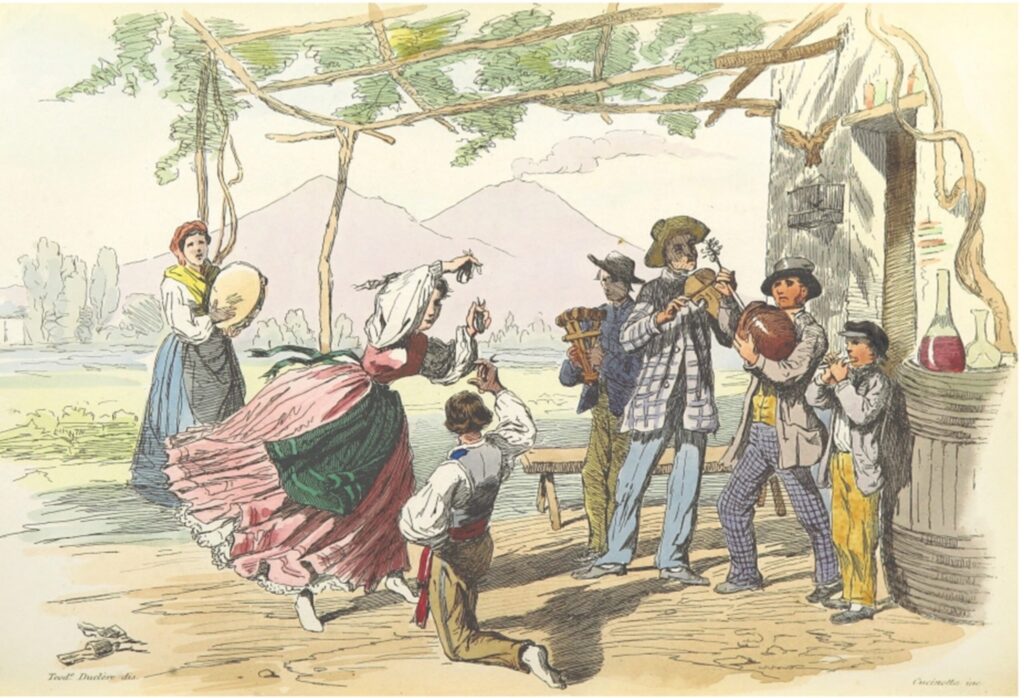

Visual documents of lazzaroni and street vendors focused on representing their dress, wares, and local customs like dancing. In Naples engravings as well as “fans, plates, and handkerchiefs” were commonly sold (Calaresu and van den Heuvel 2016, 7).9 Within these surviving artistic records, there was a sharp tension between a desire to faithfully represent the variety of lazzaroni and street vendors with a voyeuristic “picturesque” impulse that tended to depict “street sellers as poor, marginal, exotic, even deformed or deranged” (Calaresu and van den Heuvel 2016, 7).

Figure 2 reproduces three images of lazzaroni and Neapolitan street vendors, showing the range of nineteenth-century depictions of the Neapolitan urban poor. Figure 2a shows a humble street vendor selling sorbet to two children. This is an idealized scene of Neapolitan life. Set in a urban square and flanked by a church, Vesuvius erupts in the background. Both the vendor and children are depicted as impoverished (the boy is barefoot). The vendor’s smile, the sweetness of his goods, a nearby church, and the children create a scene of picturesque innocence. The lithograph of a lazzarone and a porter in Figure 2b aims at a more a realistic representation of this social class’s demeanor and dress. In contrast, Figure 2c depicts a bellowing street merchant—a melon seller—made to appear buffoonish through his disheveled appearance (his unbuttoned shirt clings awkwardly to his melon-shaped body), ridiculous hat, and gaping mouth caught in mid-shout.

Figure 2. a–c: Three nineteenth-century representations of Neapolitan street vendors.

These visual and literary documents also recorded sonic impressions of poor Neapolitans. Both Northern European and Northern Italian written accounts of Naples frequently commented on the urban noise unique to that city. Charles Burney (1773), for example, found “the singing in the streets” of Naples to be “far less pleasing, though more original than elsewhere” (369). In 1834, the Lombard historian Tullio Dandolo focused on “the cries of the sailors of the port, the screams of the vendors in the squares, the squeaking of the wheels in the streets” when describing Naples (Privitera 2023, 243). Duret de Tavel, a French official in Napoleonic Naples, wrote in 1807 that around the Via Toledo “the immense populations” of the city held “a screaming and unceasingly agitated populace,” noisier “than in any district of Paris” (Privitera 2023, 243–244). Even the engravings of street vendors recorded aspects of the associated sounds. Some illustrations were accompanied by captions of their cries, sometimes in the sonically marked Neapolitan dialect with mouths open and hands cupped to amplify (Privitera 2023, 246–250). These images also suggest that emphatic and scripted gestures were coordinated with vocal cries as depicted in the melonaro’s pose in Figure 2c.

This perceived soundscape reinforced an early-nineteenth-century stereotype that Neapolitans were naturally inclined to music (Privitera 2023, 245–246). Literary descriptions of songs from lazzaroni were common with transcriptions of poetry and music being published in the first half of the nineteenth century. Privitera (2023) has suggested that some of the Neapolitan songs that fascinated Grand Tourists likely resembled the canto a ffigliola as recorded by twentieth-century ethnomusicologists (251–252).10 The melodies of the canto a ffigliola were musically simple and metrically free with passages that resemble the reciting tones of recitative or monophonic chant. This genre of syllabic song consisted of two singers who traded a melody with little to no accompaniment. Charles Burney (1771) noted a similar musical practice where “in the streets there were two people singing alternately” in a “noisy and vulgar” manner (307–308). Burney also remarked that these canzoni could be accompanied by a calascione, an instrument similar to a guitar. Earlier in the eighteenth century, representations of Neapolitan street songs likely found their way into the comic operas of that city, complete with imitations of the calascione.11

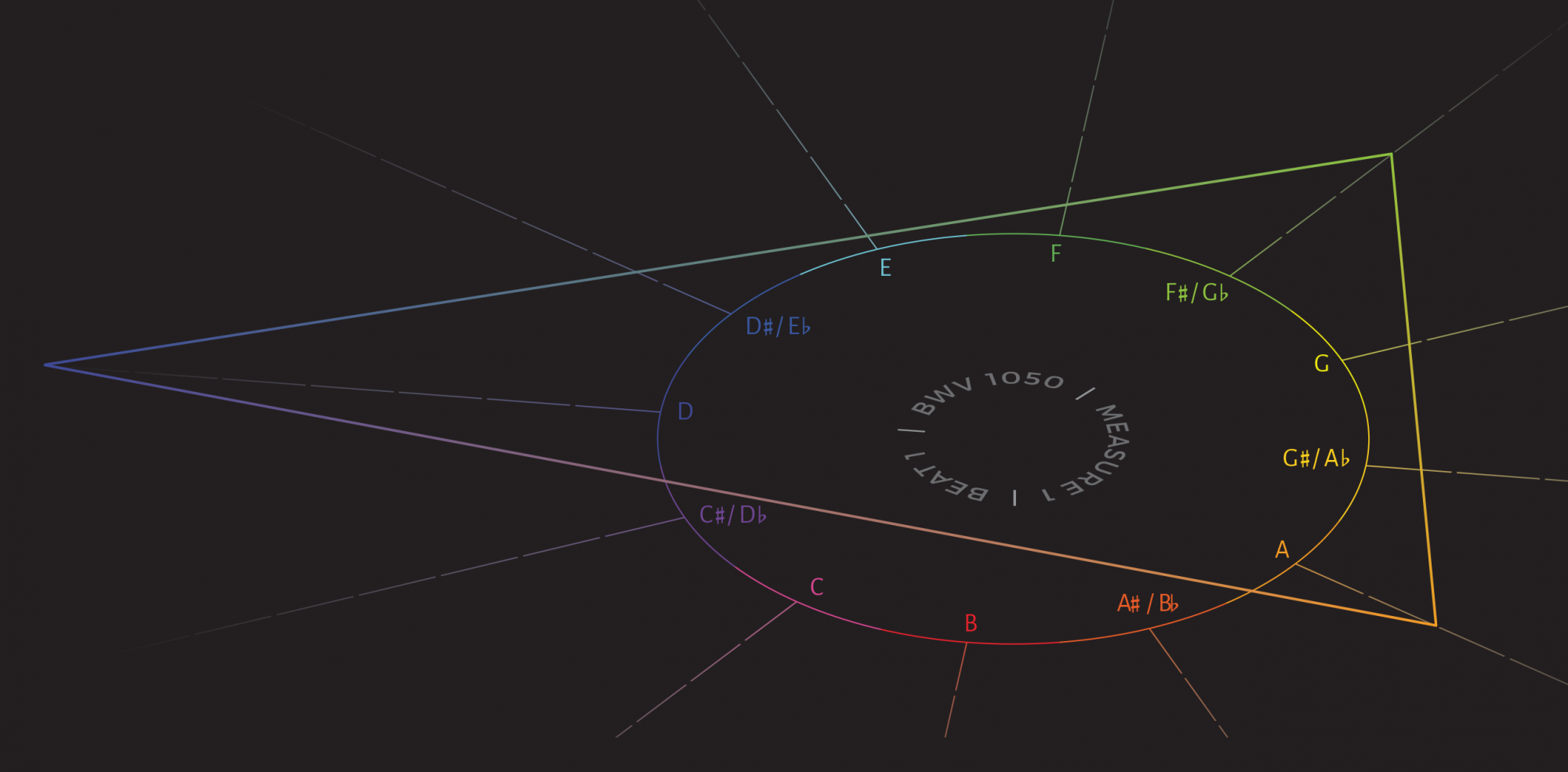

Finally, descriptions of music from the Kingdom of Naples often focused on the tarantella dance. Many images of the dance show, in addition to a dancing couple, instrumentalists playing “tammorra (hand tambour), or the smaller tamburello (Neapolitan tambourine) […], popular percussion instruments, mandolins, violins, popular wind instruments such as the Ciaramella (shawm), and the castanets used by the dancers” (Privitera 2023, 254–55). A sonically suggestive scene like this appears in the 1858 lithograph reproduced in Figure 3.

In summary by the early decades of the nineteenth century, Neapolitan poverty had acquired associations with a set of behavioral, visual, and sonic attributes. These stereotyped characteristics sometimes included an assumed wild temperament that mirrored the rustic landscape of the Italian South. In other situations, the poor Neapolitans were conflated with the lazzaroni and street vendors that could be found in public spaces and squares. The sounds associated with lower-status Neapolitans—such as dances like the tarantella, the cries of street hawkers, and an assumed innate musicality—played an important role in defining their perceived identity. Within this cultural context, The Barber of Seville premiered during the 1816 Carnival season in Rome, mere months after Rossini’s five-year Neapolitan residency began in 1815.12 Even in a central Italian city like Rome, these ideas about the temperament and sonic signature of lower-class Neapolitans would have circulated.

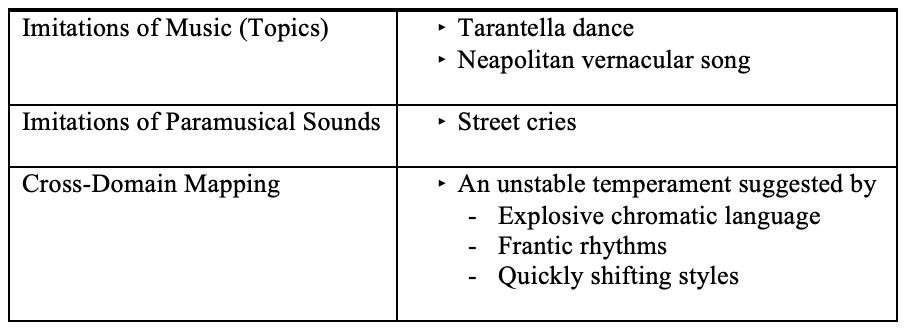

Rossini’s musical depiction of Figaro, especially in his first two musical numbers, draws on a diverse range of sonic Neapolitanisms summarized in Table 1. Some of these sonic Neapolitanisms are musical topics of which the most important are the closely related genres of the tarantella dance and Neapolitan vernacular song.13 Other Neapolitanisms in Figaro’s music are imitations of paramusical sounds, such as the noisy cries of beggars and street vendors that often were commented on by nineteenth-century writers. Finaly, some Neapolitanisms within Figaro’s numbers operate metaphorically and rely on cross-domain mapping.14 Underlying these metaphors was the classist, voyeuristic notion that impoverished Southern Italians had an unstable temperament. In his early numbers, Figaro is assigned extraverted musical gestures, which undermine a sense of composure (mapped musically to diatonicism and elegant, tempo giusto rhythms) with choleric chromaticism and frantic dance rhythms.15 Ultimately, these sonic Neapolitanisms are in dialogue with the tropes and iconographies of lower-class Neapolitans.

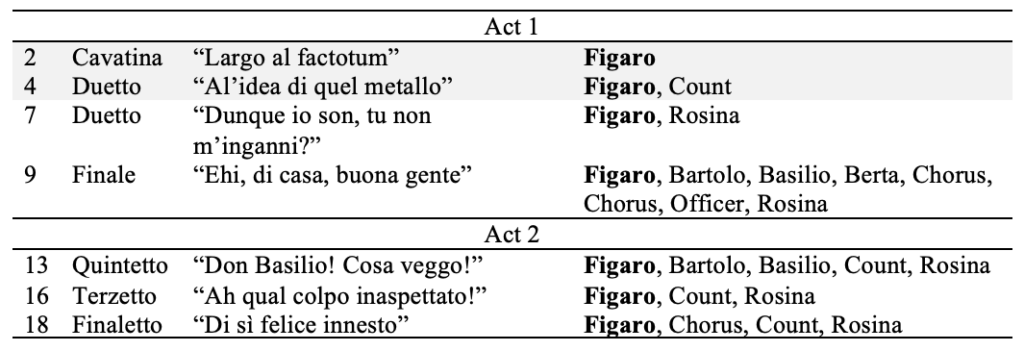

Figaro sings in seven of Il barbiere di Siviglia’s musical numbers, summarized in Table 2. After his first two numbers, which include his only solo aria and a lengthy duet with Count Almaviva, Figaro’s musical prominence recedes as he assumes an ever more supportive role in the remaining ensemble numbers. Figaro’s first two numbers, consequently, offer the best musical spaces to define his character, and it is these numbers that contain the opera’s most prominent musical Neapolitanisms.

2. Figaro’s Frenzied Tarantella

Figaro’s entrance aria, the cavatina “Largo al factotum,” is replete with sonic signifiers of Southern Italian vernacular music, especially the tarantella dance and closely related vernacular songs, which establish Figaro as an unusual basso buffo. They inflect his music with connotations of nineteenth century stereotypes of the Neapolitan urban poor, who were understood to be emotionally volatile and susceptible to overstimulation. In this section, I show how Rossini interweaves these Neapolitan topics into a comic aria in order to underscore a characterization of volatility. I begin with a brief overview of Figaro’s “Largo al factotum,” describe the typical features of the cavatina’s most prominent Neapolitanisms, and situate these within the aria’s form at four moments of psychological crisis.

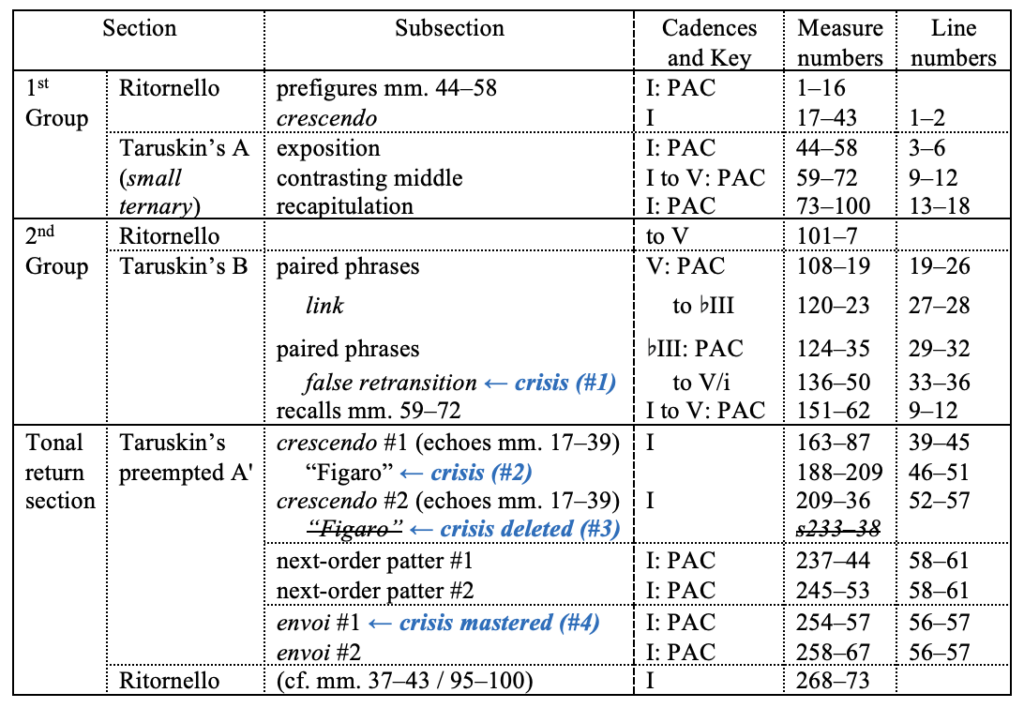

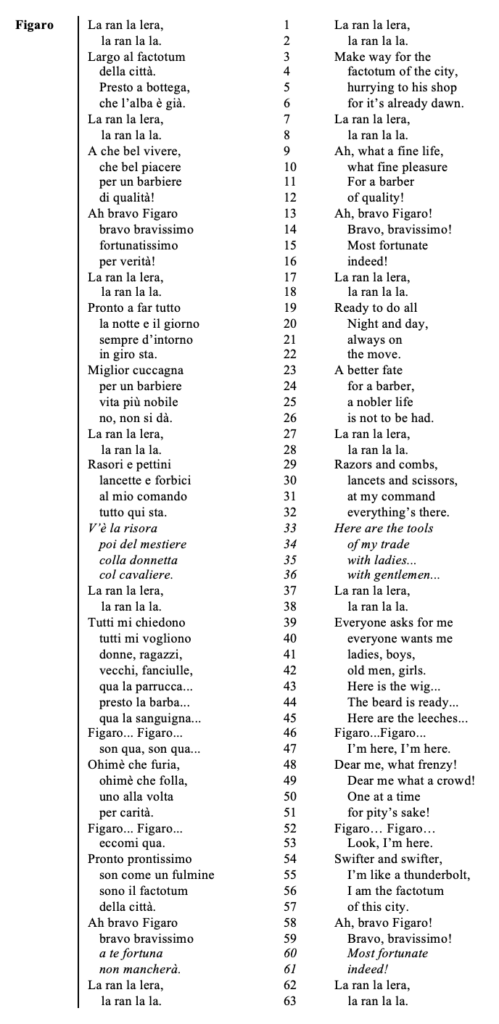

There has been disagreement on how best to interpret the form of Figaro’s cavatina. Musicologists like Richard Taruskin (2005) and Saverio Lamacchia (2008) have interpreted the aria as a modified ternary form, albeit from different perspectives. I argue, however, that its ternary characteristics can better be understood within the framework of Classical-era comic-patter aria forms.16 Both ternary and comic-patter formal interpretations are summarized in Table 3. Like many comic arias, Figaro’s begins with two thematic groups forming an exposition-like structure.17 The first group is primarily centered around the tonic (mm. 1–100) and the second, around the dominant (mm. 101–162). Following this presentation of relative formal clarity, Figaro’s number devolves into comic patter (mm. 163–273). This patter is primarily in the key of the tonic and belongs to a formal division Platoff (1990) would identify as the “tonal return section” (107). This final section of formal instability incorporates musical and poetic tropes for buffo pieces, all of which emphasize Figaro’s capricious temperament in this context. These comic elements include lists (“donne, ragazzi, vecchi, fanciulle” [ll. 41–42]), fragmentary phrases (“qua la parrucca…presto la barba…qua la sanguigna…” [ll. 43–45]), and various speeds of comic patter (an initial speed and an even brisker “second-order” speed).18 Although not the final lines of the aria, Rossini treats Figaro’s “son come un fulmine / sono il factotum / della città” (ll. 55–57) as if they were the poetic envoi in which the breakneck speed of the “second-order” patter is abandoned and those words, which encapsulate the “sense” of the aria, are “sung more slowly to emphasize its message” (Platoff 1990, 105).19

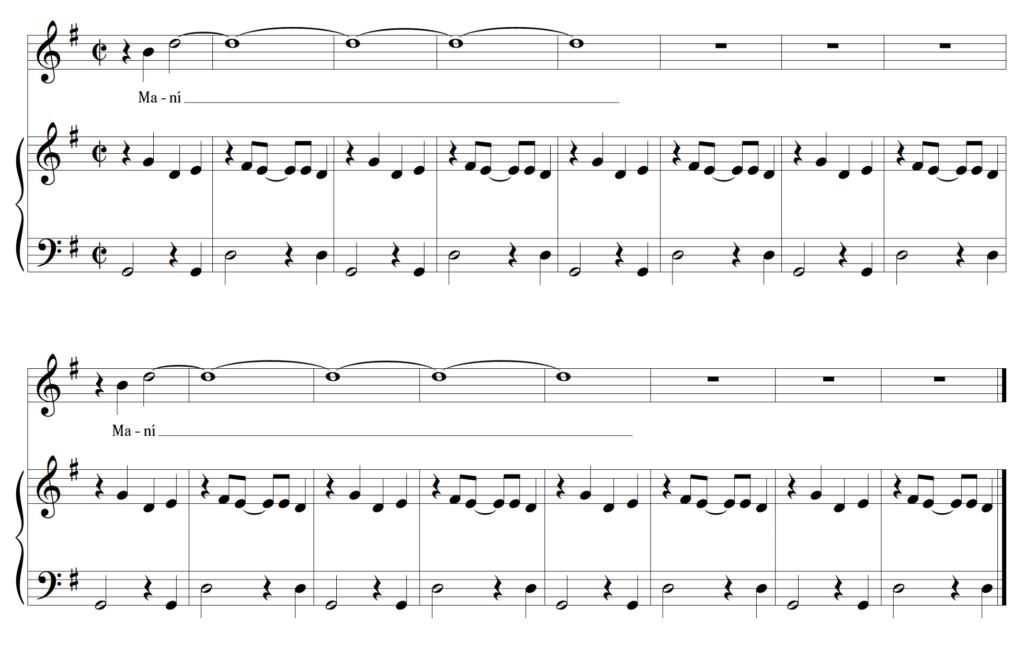

Psychological agitation pervades Figaro’s otherwise joyful cavatina, the text for which appears in Example 1. As the comic aria progresses, his boasting acquires an increasingly frantic tone, especially in lines 39–53. Figaro’s versatile professional excellence apparently becomes a burden, as his services are sought by tutti. Critics have located this agitation in Rossini’s musical language and organization for this aria. Lamacchia (2008), for instance, found Figaro’s cavatina to be quintessentially “hyperbolic,” dominated by “the music of an overexcited individual [tarantolato]” (195). Taruskin’s (2005) brief analytical description of the aria interpreted its formal plan in relation to a volatile psyche. His modified ternary reading of its relatively free formal design finds the “hilariously preempted” return to A, with it lightning-fast patter, to underscore how “Figaro is overwhelmed with thought of all the demands everybody makes on him, uniquely gifted as he is” (3:23). Similarly, Lamacchia (2008) interpreted the aria’s form as an unusual ternary, with its “abnormal,” “exaggerated,” and “tabooworthy” A’ section illustrating the “clear symptom of nature outside of the canons of the factotum” (195).

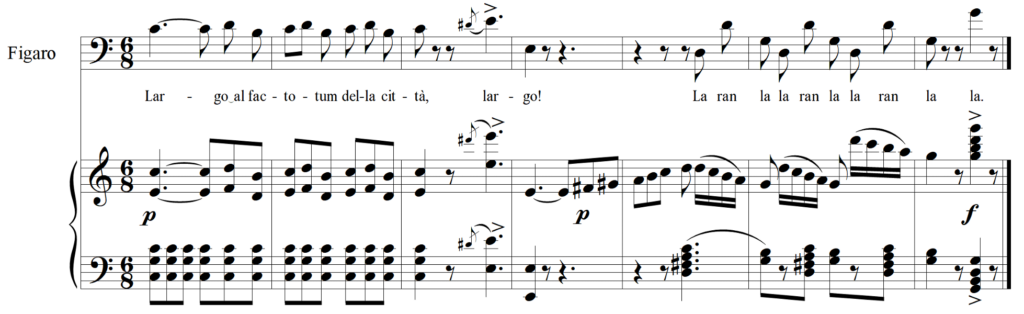

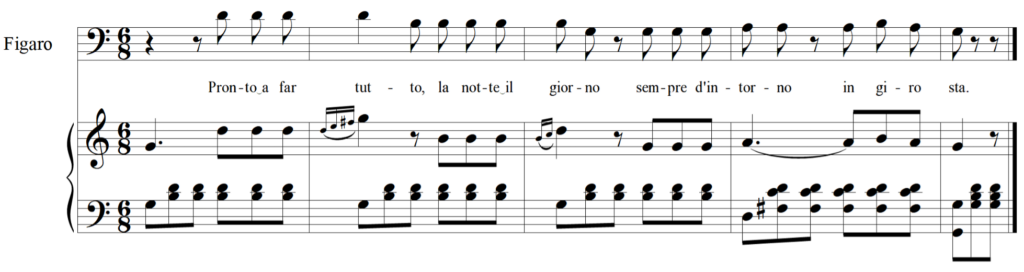

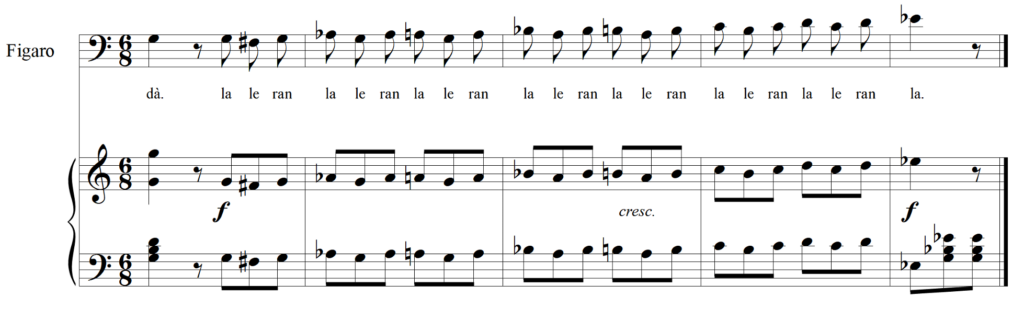

In addition to its buffa aria formal design, Rossini also conveys Figaro’s volatile temperament through shifting, extraverted musical topics (especially the tarantella dance, which dominates the aria’s second group and second-order patter), and through a series of harmonic crises marked by chromatic thirds-related progressions. Much like Figaro’s enigmatic character, the $$^{6}_{8}$$ meter of “Largo al factotum,” is topically rich, able to suggest multiple styles suitable for depicting a gregarious and impulsive Figaro. Rodney Edgecombe (2016) has interpreted this aria’s meter as suggesting a range of styles, including those of a “postilion’s song, of an aria da caccia, of a sennet, of a tarantella, and of a marche guerrière” (58). Edgecombe’s postilion, sennet (both types of fanfare), and marche best describe the aria’s first thematic group, which support Figaro’s boastful entrance. The opening phrases of this section, shown in Example 2, begin with a charging fanfare-like gesture. These measures also introduce a recuring tendency for this number to race towards thirds-related harmonies. In the third measure of Example 2, for instance, Figaro arrives on an E major harmony (IIIs in the key of C major). The grace note at this harmonic arrival also foreshadows the aria’s eventual accumulation of Neapolitanisms by evoking the sounds of tambourines and castanets. The implications of this excitable chromatic and percussive soundscape are only thoroughly realized in the aria’s second thematic group where they coincide with the appearance of Southern Italian musical topics.

In the second thematic group, beginning with the passage reproduced in Example 3, Rossini transforms the quality of this $$^{6}_{8}$$ meter to allude to the tarantella dance and other vernacular Neapolitan musical traditions. Although not an exhaustive list, the tarantella often displayed the following musical features, most of which appear in the second thematic group of Figaro’s cavatina:20

- $$^{6}_{8}$$ meter, with anacrustic rhythms

- Fast tempo

- Minor mode

- Instruments evocative of the Italian South

- When texted, nonsense syllables such as “la”

- Frantic chromatic harmonies

- Highly contrasting tonal areas

The tarantella was a fast dance in $$^{6}_{8}$$ or related compound meter, often cast in the minor mode.21 As seen in Example 3, this $$^{6}_{8}$$ meter was often given an anacrustic impulse, with eighth-note figures leading from weak to strong beats.22 The Milan-based critic Peter Lichtenthal (1836,) described the tarantella through its rhythmic and metrical profile, writing that it is a “Neapolitan dance of a joyful character with a melody in $$^{6}_{8}$$ and a fast tempo” (2:237). The dance was emblematic of the Kingdom of Naples, especially its southern Apulia region. Contemporaneous discussions of the tarantella reveled in its geographic associations by addressing its dubious origin as an energized dance to purge the venom of a tarantula bite.23

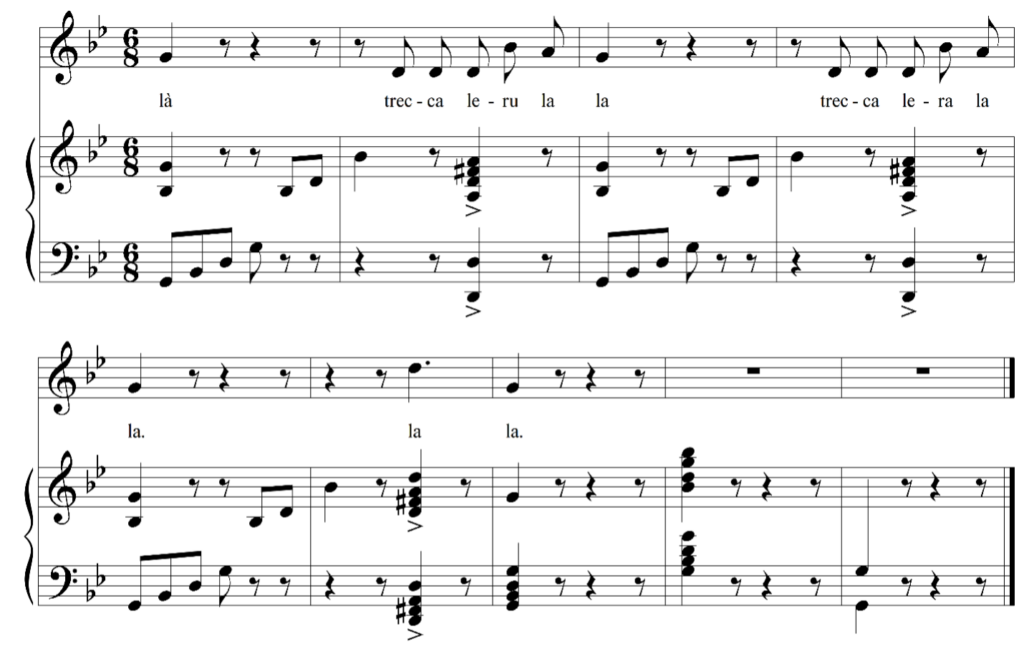

Aside from the tarantella’s meter and affect, Lichtenthal also commented on the dance’s Southern Italian instrumentation, mirroring nineteenth-century iconographies of the rustic tarantella as represented in the image of castanet and tambourine players in Figure 3 above. Lichtenthal (1836), for example, indicated that the dance was “ordinarily accompanied by a colascione or tambourine” (2:237). Stylized published tarantellas, like Rossini’s song “La danza” from the Parisian parlor set Soirées Musicales (1836), might even imitate these instruments with pianistic effects. In “La danza” an arpeggiated piano accompaniment, sometimes staccato, resembles a plucked colascione; fast grace notes in the upper register of the piano, especially in the final measures of the opening and closing piano ritornellos, create a tambourine-like effect. In texted tarantellas, joyful nonsense syllables like “la” would appear, as can be seen in Guglielmo Cottrau’s “Nuova tarantella” (Example 4) and in Rossini’s “La danza” (Example 5).

The lilting rhythms, constant $$^{6}_{8}$$ meter, minor mode elements, and cantabile melody of the second thematic group of Figaro’s aria are just as suggestive of Neapolitan song as the tarantella.24 Of the 112 “Canzoni Napoletane” transcribed and composed by Guglielmo Cottrau in the collection Passatempi musicali (1865), 78 songs (nearly 73%) were cast in a compound meter with the overwhelming majority of those in $$^{6}_{8}$$ (73 songs). Simple meters in the Passatempi musicali collection were significantly more likely to be assigned origins outside of Naples and its environs. Out of the 30 simple meter songs from this collection, many were of ambiguous geographic origin. Of the 11 annotated as non-Neapolitan, most (9) were ascribed a Sicilian origin.

Vivid chromatic harmonies, distant tonal shifts, and striking modal contrasts appeared in nineteenth-century tarantellas as a means of intensifying the dance’s frantic energy. Cara Stroud (2021) recently identified destabilizing chromatic harmonies and distant tonal relationships as defining features of a “crisis” subtype of nineteenth-century concert tarantellas. Stroud proposes that such tarantellas construct narratives of crisis through the “near obsessive fragmentation and repetition of short melodic ideas, the regular use of highly chromatic sequences, [and] the emphasis on distantly related keys” (248).25 These musical devices were deployed to depict a “frantic dance to ward off death” (247). Conversely, according to Stroud, other tarantellas could have a more overt “humorous” expressive orientation, “characterized by [their] virtuosic excess” (247). As a genre of concert music, tarantellas of Stroud’s crisis subtype included works like Daniel Auber’s “Tarantelle” from La Muette de Portici, Frédéric Chopin’s Tarantella, op. 43, the finale to Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Suite No. 2 for two pianos, and the closing movement of Franz Schubert’s Death and the Maiden string quartet, D. 810 (248).

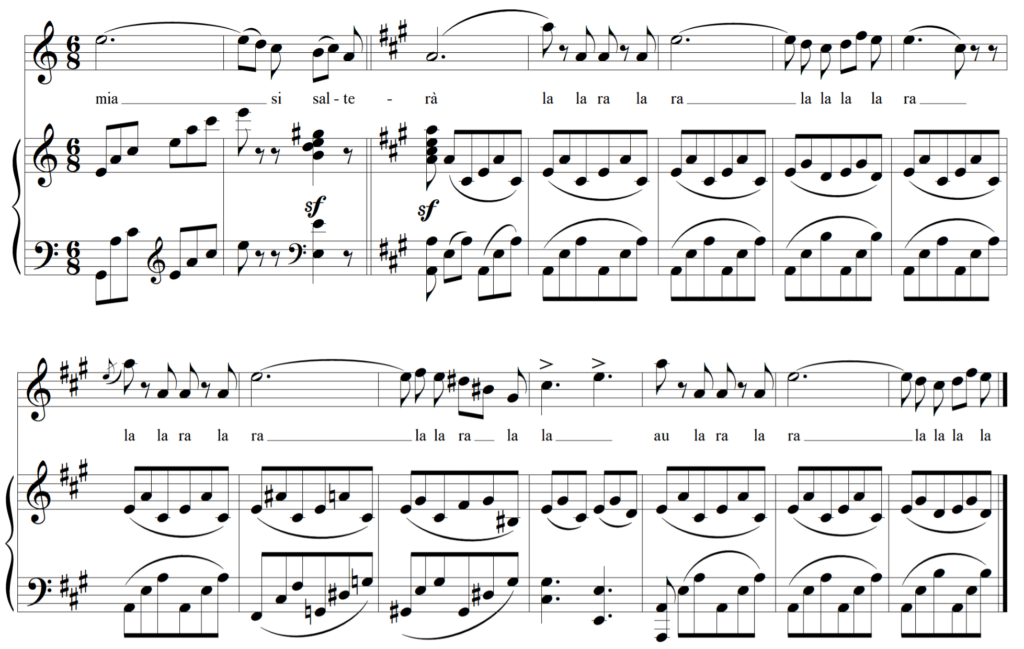

Even in tarantellas that Stroud identifies as members of the “humorous” rather than “crisis” subtype (like Rossini’s “La danza”), frantic energy, chromaticism, and modal contrasts permeate musical textures. This can be seen in the saturation of neighbor-note figures in the accompaniment of “La danza,” reproduced in Example 6, and in the abrupt shift from A minor to A major in Example 5. Figaro approximates this kind of energized musical line, inundated with neighbor tones, in a linking passage within “Largo al factotum’s” second thematic group, shown in Example 7. Similar melodic lines can be seen in the folk-oriented “Nuova tarantella” (Cottrau 1856), shown in Example 8. The passage in Example 7 also sustains the tarantella topic through two additional elements: the use of nonsense syllables on “la” and a distinctly Mezzogiorno-inspired harmonic sliding.26

Figaro’s cavatina also combines elements of Stroud’s “crisis” and “humorous” tarantella subtypes, one in which comedic virtuosic display descends into volatile crisis. Depending on the choices of a director or singer, this distress could be either sincere or feigned. In “Largo al factotum,” these cresting waves of psychological crisis are created by passages that adopt chromatic third tonal relationships, especially in the aria’s second thematic group and tonal return sections. Here, Figaro loses mental control over the harmonic sphere in two pronounced moments of tonal and psychological crisis before mastering his emotions in the aria’s concluding passage of stringendo patter.

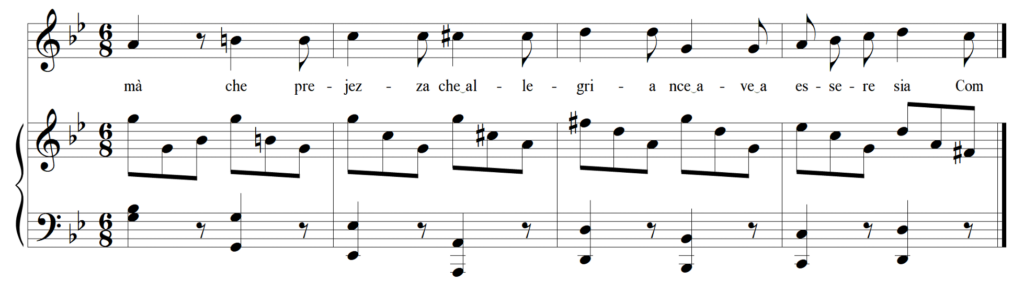

Crisis (#1): The second thematic group of Figaro’s cavatina culminates in the number’s first moment of crisis. The vocal tarantella melody, which begins in the aria’s dominant key as seen in Example 3, eventually leads through a series of descending chromatic thirds that conclude on the dominant of the minor tonic.27 A linear sketch summarizing this large-scale tonal plan descending from G to E$$\flat$$ to C to A$$\flat$$ appears in Example 9. I contend that this chain of thirds stages the exhaustion of a temperamental crisis.28 The poetry of this section has Figaro speak about his “night and day” schedule, always at work, “always on the move” (ll. 20–22). When paired with the frantic tarantella, the move towards chromatic third relations and harmonies borrowed from the minor mode acquire a sense of exhaustion or even self-doubt. By this section’s end in mm. 136–150, shown in Example 10, Figaro’s boisterous tarantella fades from the texture. In its place, a muted pianissimo dynamic, the abandonment of constant eighth notes, and the pronounced shift to a dark C minor create a subtle moment of contrast in a section otherwise characterized by the gestural language of the tarantella.

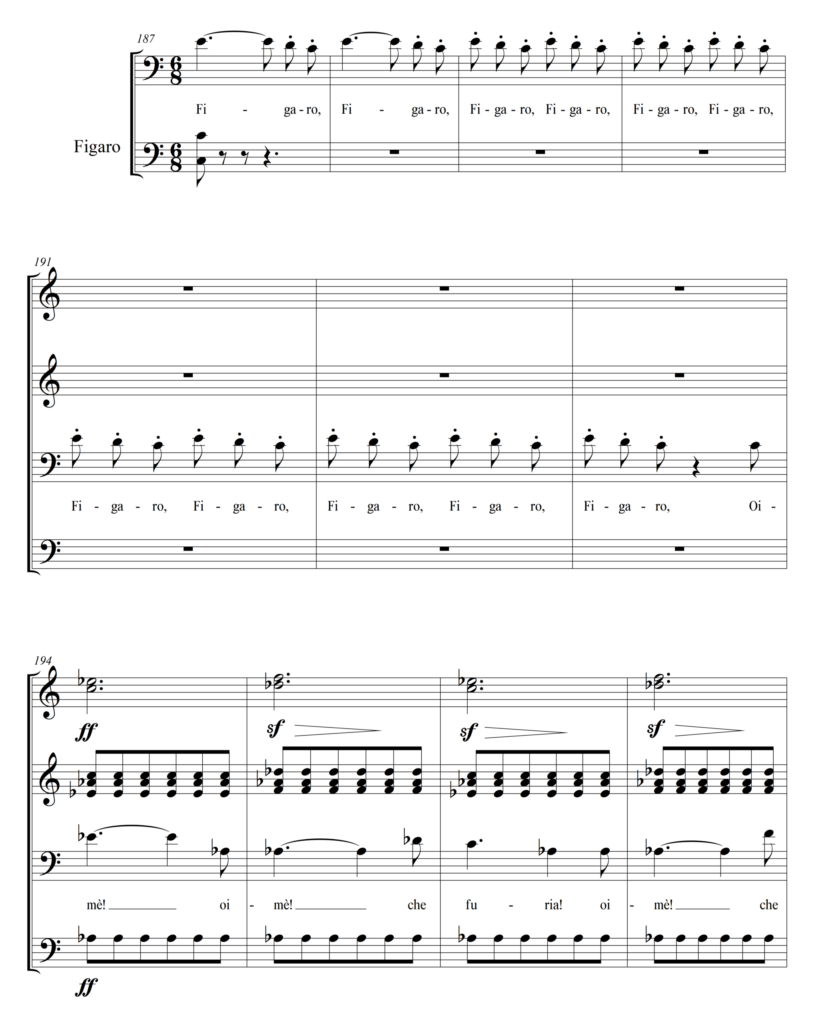

Crisis (#2): The second moment of crisis appears in the aria’s patter-dominated tonal return section and culminates with a descending major thirds cycle in mm. 193–209, shown in Example 11. This passage begins with the cavatina’s famous agitated cries of “Figaro.” The shouts of the barber’s name actualize the calls from everyone that Figaro comically listed in the preceding stanza: “tutti…, donne, ragazzi, vecchi, fanciulle…” (ll. 39–45). This inventory of patrons, characteristic of buffa arias, is set to a slowly accumulating vocal patter, and given a frenzied musical presentation through the use of a Rossini crescendo. The accelerating turns from tonic to dominant in this crescendo, along with the grating martial instrumentation of piccolo and trumpet, transform Figaro’s entrepreneurial success into an endless and exhausting military campaign. Fanfare-like calls in Figaro’s patter melody emphasize an oscillating line between $$\hat{1}$$ and $$\hat{2}$$, which, based on the opening ritornello’s presentation of this thematic material, should end on $$\hat{1}$$ in m. 210 (compare with m. 41). However, this promise of tonal closure at the conclusion of the crescendo is denied.

The calls of “Figaro,” starting on $$\hat{3}$$, begin where this resolution to $$\hat{1}$$ should have occurred. The repeated vocal statements of “Figaro” evoke the cacophony of urban street cries but in reverse: here it is the customer, not the vendor, who shouts out. Recalling the descending chromatic thirds of the first crisis, Figaro’s psychological panic is manifested through a major thirds cycle from C to A$$\flat$$ to E to C. The medial stages of this harmonic path are realized with searching dominants that seek a way out of this delirious conundrum.29

Figaro’s volatility is reflected in the voice leading path traced through this descending thirds progression. Although many nineteenth-century examples of these harmonic root motions tend to follow rigorously the same voice-leading connections from one stage to the next, in this passage, each voice-leading seam is given a different stitch. The motion from an implied C major triad to the A-flat major of m. 193 is sudden and direct. No equivalent move appears in the path from A-flat to E major. Instead, the motion is arduous and protracted. In mm. 197–201 Figaro slowly inches away from A-flat, first by having the bass introduce a chordal seventh (A$$\flat^{4}_{2}$$) which then falls to an unstable F, one that supports a root position F dominant seventh sonority rather than a first inversion triad. By m. 200, the identity of the F7 chord shifts to an augmented sixth of E major, realized not only through the notational shift away from E$$\flat$$s in favor of D$$\sharp$$s but also by the cautious revoicing of instruments so as to avoid the scalding heat of this localized sharp.

Crisis Deleted (#3) and Crisis Mastered (#4): Although the harmonic extremity of mm. 193–209 stands as the final passage of “crisis” within the aria, Rossini prepares and denies two additional moments of crisis. Both of these reinforce the tonal return section’s cyclic design. Each contain three paired sections of increasingly shorter length: (1) a repeated crescendo section, (2) a repeated “next-order” patter section, and (3) the repeated rhetorical envoi. “Crisis #2,” discussed above, appeared at the close of the initial half of one of these paired sections, the crescendo #1. Rossini follows this passage with a return to the twenty-four measures of the crescendo material that initiated the A’ section of the aria in m. 209.

The second crescendo material is largely identical to what had been heard before. Its most significant changes pertain to Figaro’s sung text, which now focuses on ll. 52–57 of the aria and eventually repeats “Figaro qua, Figaro la” in a fit of accelerating comic patter. The textual repetition and patter declamation illustrate a character who, in typical buffo fashion, increasingly struggles to regulate his emotions. The first time this material was heard, it led to the crisis-inducing calls of “Figaro” and the subsequent patch of thorny chromaticism. The second time, however, the repetition, leads to an energetic spate of octave Cs in mm. 233–236 that prepare the subsequent stringendo close—no parallel and culminating passage of psychological distress emerges.

Yet, Rossini’s autograph indicates that these four measures of octave Cs were a late addition to the score. They were written on an insert pasted over a “crossed out” sketch. That sketch originally included six measures of “Figaro” cries identical to those heard at the close of the first passages of crescendo rhetoric in mm. 187–193 (Rossini 1816 [1993], 35–36). This alteration not only prevents another iteration of comic distress (i.e., “crisis” has been avoided), but it also reveals Rossini’s underlying paired construction for this aria’s close.

The subsequent stringendo reverses and masters the harmonic processes of “crisis” that appear earlier in the aria. Here, tarantellistic “crisis” is largely created through patter that threatens linguistic syntax and chromatic thirds harmonic progressions. Figaro’s closing stringendo presents two alternatives to crisis-inducing patter and harmony. The closing stringendo, identified as “

next-order patter” in Table 3 (mm. 237–253), returns Figaro’s music to a clear tarantella topic. Although it contains the fastest sustained passage of patter declamation in the aria, it projects celebratory mastery rather than psychological distress. Rossini created this effect by setting text that unambiguously praises Figaro himself (“Ah, bravo Figaro, a te fortuna non mancherà”) and by supporting this music with a slowly unfolding diatonic authentic cadential progression (I–IV–V7–I). When this eight-measure module repeats, Figaro replaces “Ah, bravo Figaro” with the joyful “La la ran la.” In mm. 254–267, the aria’s envoi (“Sono il factotum della città”) continues this process of confident mastery over musical and poetic elements of “crisis.” Here, patter is abandoned in favor of declamatory song. The twirling tarantella accompaniment of mm. 237–253 transforms into a grandiose homophonic texture. This passage also features a harmonic progression that emphasizes descending diatonic thirds in the bass (I–vi–ii6–V–I). This rhetorical shift to a diatonic rather than chromatic thirds progression stands as a foil to the two previous chromatic descents that led to moments of psychological insecurity. Only in the envoi, with the abandonment of patter and chromaticism, does Figaro confidently declare that he “[is] the factotum of the city” (ll. 56–57).

In sum, the stylistic language of Figaro’s “Largo al Factotum” presents sonic signifiers of southern Italians. The central musical topic of the cavatina is the frantic tarantella dance. Although the tarantella signifies by virtue of its sociocultural associations, these meanings are only determined within the context of the aria by how Rossini integrates it into its tonal and formal structure. The cavatina’s rhythms, melodies, poetry, and chromatic harmonies exude a flamboyant gestural language, one indicating a loss of psychological control. Rossini amplifies these qualities in Figaro by having his wild chromatic language center on two moments of harmonic and contrapuntal crisis. These crises disrupt the stability and propriety of cadences. Moreover, the second of these crises (coinciding with the famous passage of “Figaro, Figaro, Figaro”) stages a volatile mental breakdown. This is sonically realized with an extreme instance of a descending chromatic major thirds cycle, which equally divides the octave. The most immediate resolution to I is sonically weak. Only in the concluding stringendo does Figaro correct these moments of chromatic thirds descents with multiple statements of complete cadential progressions whose bass lines pass from $$\hat{8}$$ to $$\hat{6}$$ to $$\hat{4}$$ to $$\hat{5}$$.

3. Figaro the Street Vendor

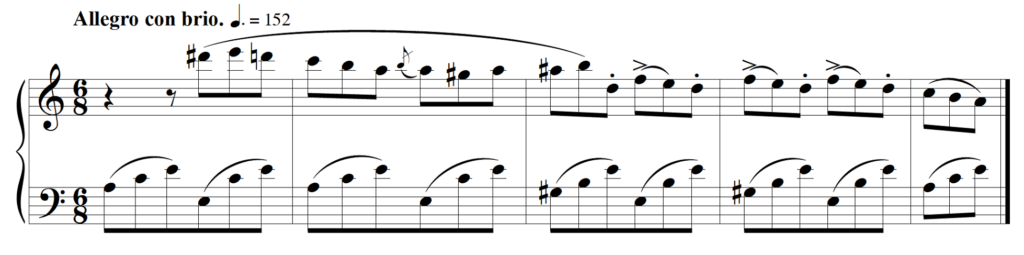

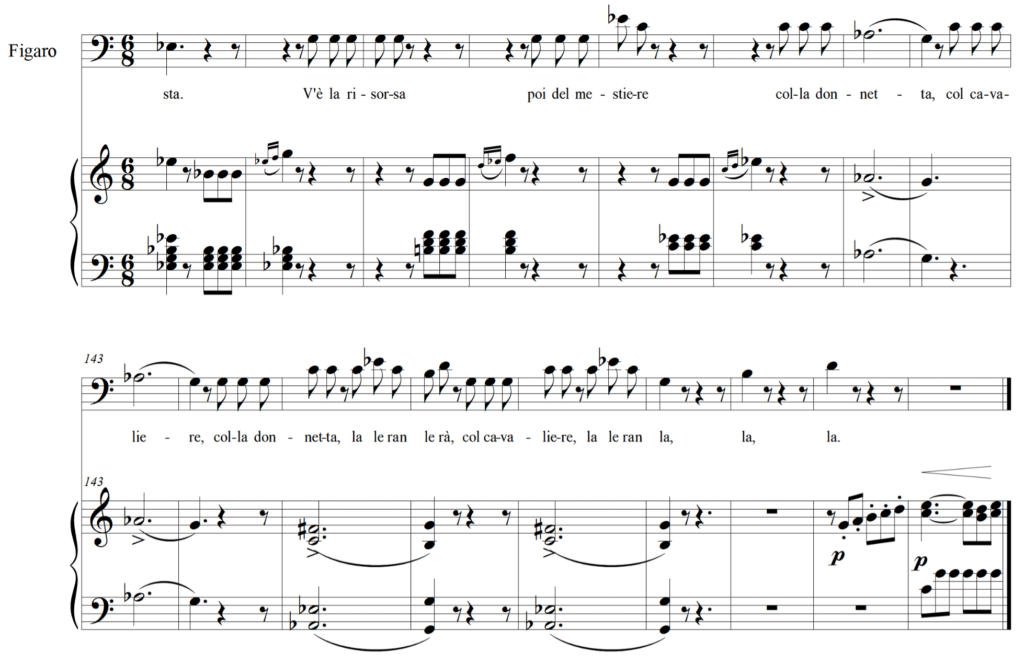

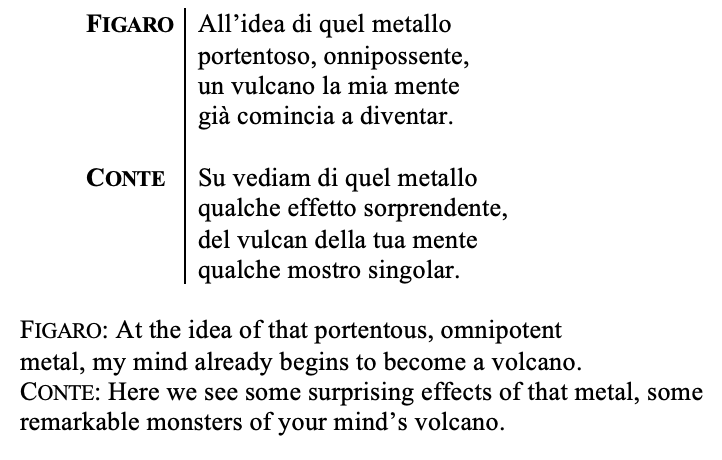

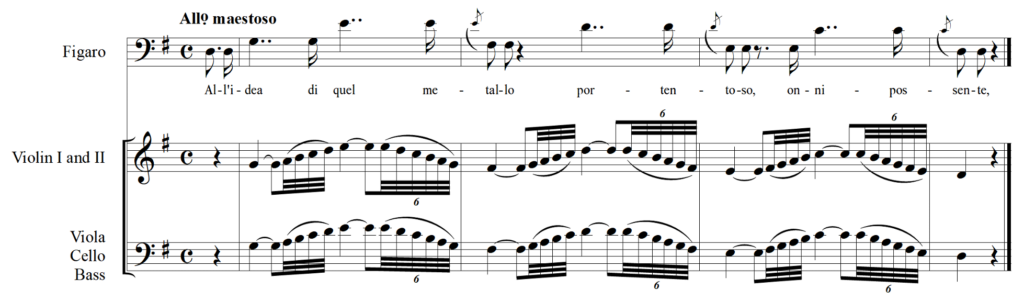

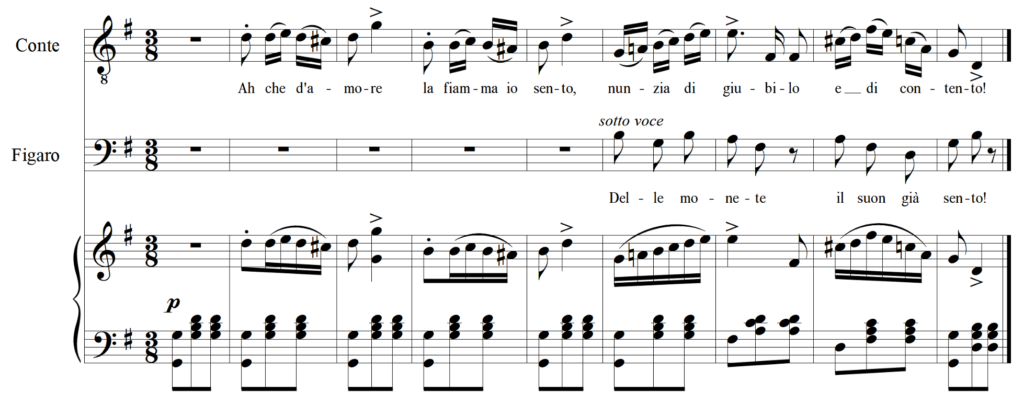

The first act duet “All’idea di quel metallo” from Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia—the second number that includes Figaro—creates a sonic portrait of Figaro that likens him to a Neapolitan lazzarone. The duet opens with a gesturally provocative phrase. Unison strings shadow Figaro’s compound vocal melody, shown in Example 13. Rossini’s exaggerated gestural language vividly conjures a stumbling, inebriated gait, seen in its portamento-like scalar fragments in the strings and hiccupping dotted rhythms that pass through the vocal passaggio.30 The subsequent phrase, a much brisker vivace, has Figaro compare his mind to an explosive volcano, like Mount Vesuvius towering over the Gulf of Naples, shown in Figure 4.

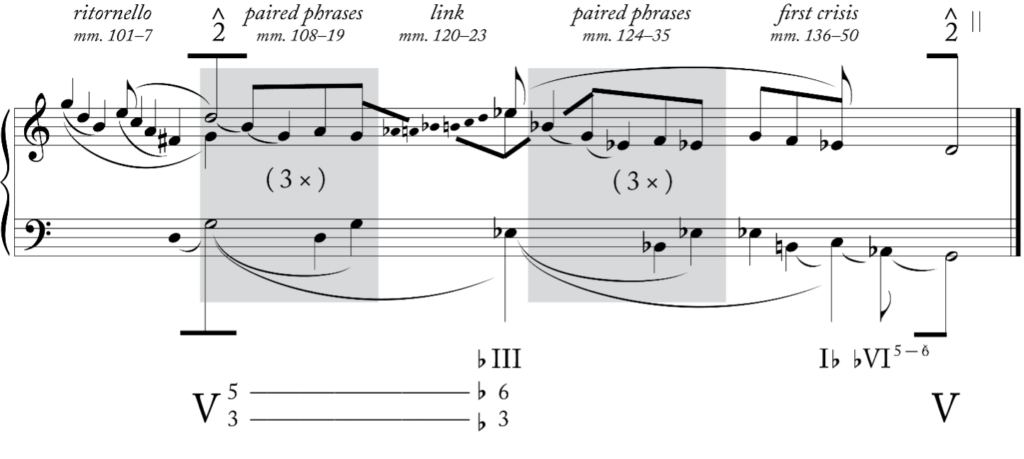

At the duet’s midpoint—its central tempo di mezzo section—Figaro adopts additional musical characteristics of Neapolitan lazzaroni. At this point in the number, Figaro and Count Almaviva have devised their first plan to woo Rosina. Before they exit the stage in preparation for the comic-disguise antics of the first act finale, the Count asks where he can find Figaro’s shop. Figaro responds by gesturing toward his shop and by providing a description of it.

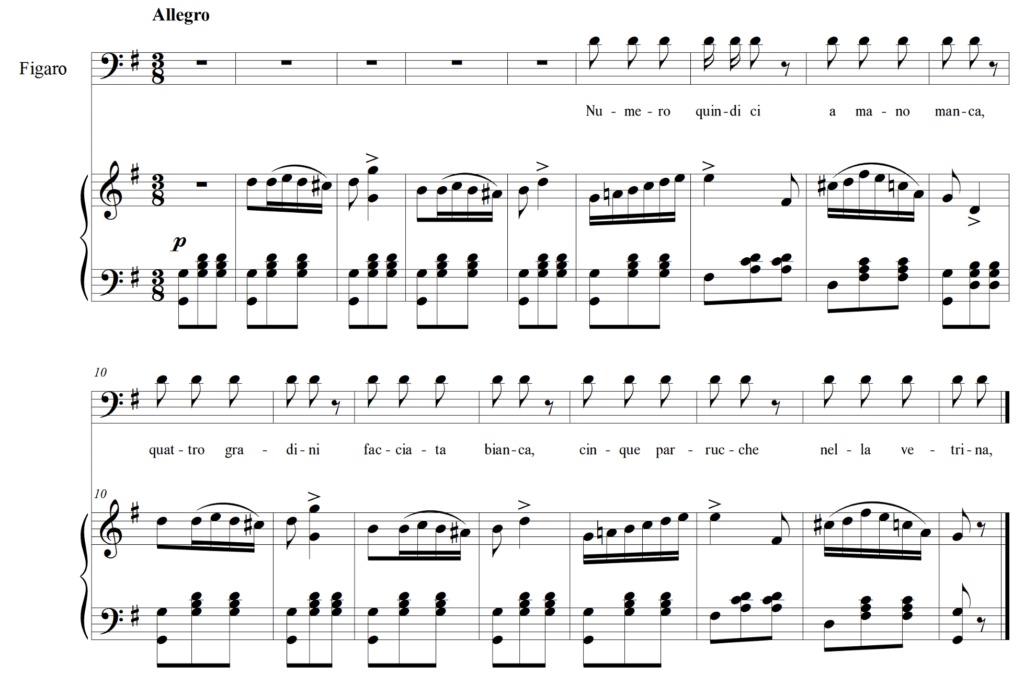

He sings this information on a series of intoned Ds (“numereo quindici a mano manca”) which are barked over a twirling, pianissimo waltz in the solo winds, shown in Example 14. This unusual mode of vocal delivery is decidedly non-melodic. Janet Johnson (2004, 168) hears his “seventy-three iterations of the common tone D” as highly unusual, describing them as a metronomic means of driving the plot forward. The mid-nineteenth-century composer Abramo Basevi (2013, 36) identified his Ds as a passage of half-spoken, half-sung parlante armonico. Although there is a striking difference between Figaro’s vocal melody and the eight-bar cantabile tune in the orchestra that spins-out into a classic “Rossini crescendo,” his parlante armonico presents a rich moment in the relationship between the voice and accompaniment. Above the lyrical tune, Figaro sings simple quinario rhythms. As if echoing Figaro’s speech, similar rhythms pervade the orchestral part.

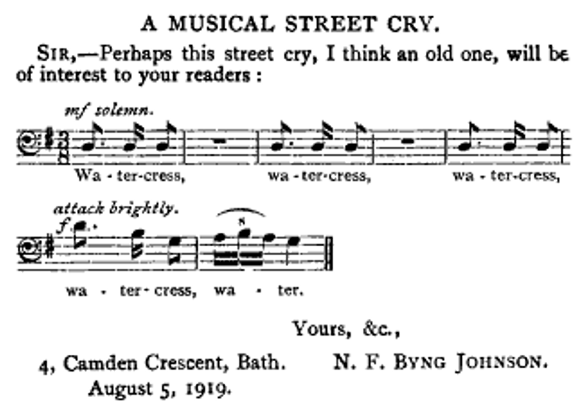

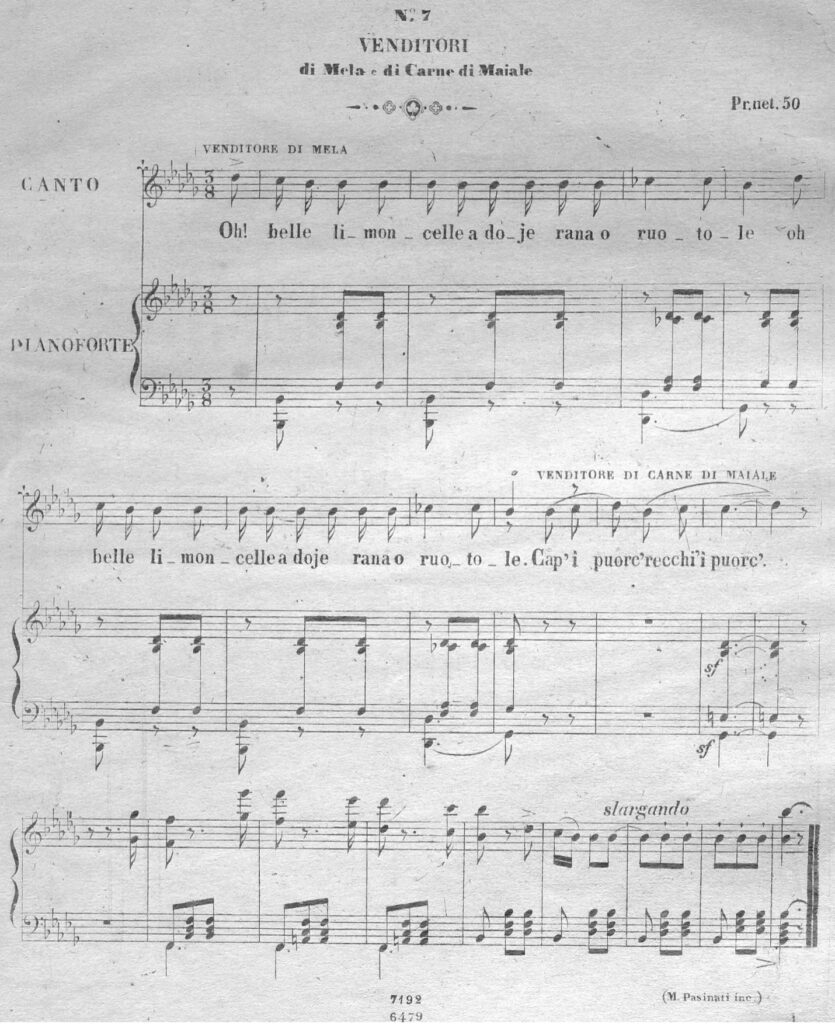

In addition to being parlante, Figaro’s melodic vocabulary imitates the cries of street vendors that sounded in pre-industrial European cities. Typical street cries relied on “stereotyped phrases” that served as each vendor’s “musical trademark” (Maniates and Freedman 2001). Street cries, although possessing great variety, were musically simple. The tune “Hot Cross Buns,” for instance, originated as an English street cry. When street cries were notated, this musical simplicity was preserved. Like “Hot Cross Buns,” the Neapolitan street cries arranged and transcribed by Federico Ricci in Example 15 have a narrow melodic ambitus, in this case, of a minor third.31 The calls of the venditore di mela has the hawker intone most of their text on a single pitch ($$\hat{1}$$).

Other street cries, like the English one reproduced in Example 16, more closely resembled the non-melodic intonation of Figaro’s Ds. The “old street cry,” submitted to the Musical Times (Johnson 1919, 494), shares several features with Figaro’s parlante. The dactylic rhythms of the word “watercress” ( – ∪ ∪) are musically rendered with a simple rhythmic figure []. Melodically, an intoned $$\hat{5}$$ is used as a reciting tone, just as in Figaro’s “numero quindici.” More recently in the late 1920s, the popular Cuban song “El Manisero” (The Peanut Vendor) imitated the cries of a street merchant in ways reminiscent of Figaro’s parlante. As seen in Example 17, yells of “Maní” (peanuts) emphasize a sustained $$\hat{5}$$. Furthermore, like Figaro’s example, the street cry occurs over a harmonically simple dance that oscillates between tonic and dominant. In “Numero quindici,” this dance is a waltz; in “El Mansiero, it is an ostinato rhumba.

Street cries like Figaro’s acted as a rare topic within nineteenth-century Italian opera; they depict travelling merchants, especially those from the periphery of society.32 The street-cry allusion colors Figaro’s character, at least at this moment, as distinctly low in rank. It also suggests a rougher vocal delivery than is typically heard in performances today. In the case of Figaro, the street-cry allusion evokes the world of street hawkers, those of the same standing as Eliza Doolittle, the flower girl, from Lerner and Loewe’s My Fair Lady. In this regard, it is perhaps an even baser vocal texture than comic patter. In this light, Figaro’s intoned Ds in “Numero quindici” suggests a deliberately unrefined and gritty vocal performance in order to imitate the wails of street vendors.

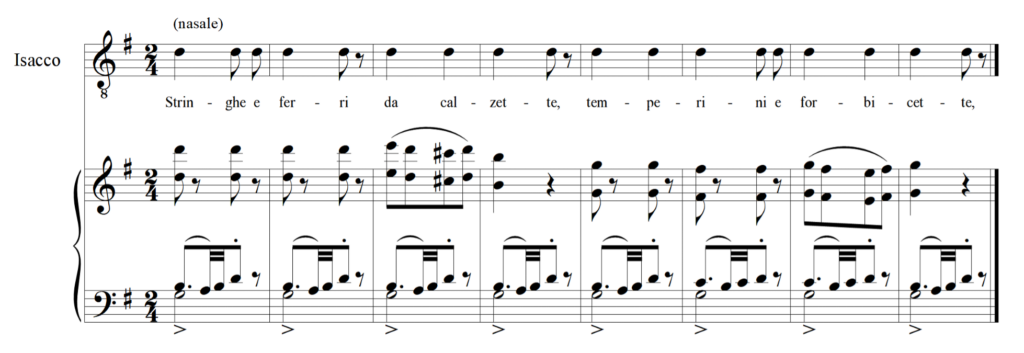

In act 1 of La gazza ladra (1817) this style of music depicts the calls of an itinerant Jewish peddler, the haberdasher (merciaiolo) Isacco. In Example 18, he is heard hawking an assortment of wares that include strings, needles, scissors, and matches. Rossini’s depiction of Isacco is also explicitly framed around his profession and Jewish identity.33 Nineteenth-century listeners used both streams of associations to interpret Isaaco’s music. Rossini’s contemporary, the French novelist Stendhal, for example, identified Isacco’s cavatina as both distinctly Jewish and Neapolitan in character.34 Stendhal’s racist and classist interpretation drew on antisemitic tropes and a voyeuristic impression of the Neapolitan poor, which he conflated. Stendhal heard this street cry as evoking “the meanest squalor of civilization,” a stark image of bleak poverty (Stendhal 1957, 266–67). In a footnote to this passage, Stendhal went further and likened “Polish Jews” to Neapolitan lazzaroni, which he called the “swindlers who plague the Kingdom of Naples” (274). Stendhal’s comments suggest that the sounds of street cries could evoke images of destitute Mediterranean poverty.

Finally, Figaro’s conduct within the duet highlights careful consideration given to the Count’s superior social standing. Throughout the number, Figaro serves and guides the Count through deferential musical cues, offering a supportive dominant here and a tuneful melody there. In this way he also acts like a street vendor selling goods. His hawking Ds transform their accompanimental waltz melody into a commodity to be traded, like the sorbet and melons sold in Figure 2 above. In effect, it is the promise of the unsung and accompanimental waltz tune—not a description of his shop—that is the true focal point of Figaro’s street call. The Count’s eventual adoption of Figaro’s hawked tune in the duet’s cabaletta—along with Figaro’s celebration of coins in his supporting bass line—seems to confirm its status as a traded commodity, see Example 19. Moreover, the waltz melody could have served as the first statement of a cabaletta theme, yet Figaro sycophantically abandons this potential cabaletta and concludes on a dominant instead, one which prepares the Count for his cabaletta entrance. In the true cabaletta, the Count sings the youthful waltz, while Figaro relegates himself to non-melodic vocal interjections that celebrate the sound of coins.

4. Conclusion

Although Rossini’s act 1 music for Figaro contains many Neapolitanisms that evoke the urban poor, Figaro’s status as a character is more complex than being a mere lower-status comic character. Figaro is in many ways enigmatic, and he amounts to more than only the class and national connotations of his musical vocabulary. Yet the question remains, which Figaro can listeners encounter in performances of these numbers? Is he a volatile beggar, like a Neapolitan lazzarone? A humble hawker of wares? A servant factotum? Or, is he a successful and clever merchant, able to manipulate the characters around him? I see two opposing strategies for interpreting Figaro’s musical Neapolitanisms: one of sincerity and the other of irony.

The first strategy would be to take Figaro’s sonic evocation of Naples at face value. If, Rossini’s Figaro is often made to sound like a lower-status Neapolitan, then perhaps he is to be presented in that way in performance, endowed with the stereotyped temperament that wealthy opera goers would have ascribed to them. Within this framing, he is depicted as a man subject to surging whims and exaggerated reactions. In “Largo al Factotum,” a wild tarantella dance suggests physical and mental delirium. The moments of psychological crisis within the number reveal a witty character in sincere distress. Perhaps he is able to be fooled by those who outrank him, at least until he masters his emotions by the aria’s close but only after expending considerable effort. In the case of “Numero quindici,” Figaro’s street cries suggest a performance with a coarse vocal timbre and exaggerated physical gestures, so that he, like the venders in Figure 2, may earnestly try to secure the Count’s employment.

An opposing strategy would be to interpret Figaro’s Neapolitanisms as ironic. As discussed above, Figaro is a unique character. Much like Così fan tutte’s Don Alfonso, he has the rare ability to see, understand, and manipulate the conventions of opera in order to achieve his goals. In this regard, Janet Johnson (2004) interprets him as a “machinist,” simultaneously inhabiting the role of “character and author,” and, as a machinist-author within the opera, he “weaves the intrigue and leads the theatrical action” (167). Along these lines, Emanuele Senici (2019) hears Figaro’s cavatina as foregrounding the “The staging of an opera performance… Before we see him, we hear him sing in the wings. … Once he enters with his guitar, he does not star this cavatina with meaningful words, but with two nonsense lines, ‘La ran la lera, la ran la là,’ just like a singer warming up before going on stage” (105). The Neapolitanism, then, are another kind of performance on the part of Figaro. Instead of revealing an essential aspect of his character, they serve as a feigned performance, playfully depicting his versatility. In the “Numero quindici” duet, Figaro adopts these Neapolitanisms to manipulate the Count, playfully subordinating himself to Almaviva. As a character with a rich and contradictory musical language, performers and directors can choose how to situate their performances of Figaro within these two extremes.

References

Allanbrook, Wye Jamison. 1983. Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart: Le Nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni. University of Chicago Press.

Basevi, Abramo. 2013. The Operas of Giuseppe Verdi. Translated by Edward Schneider and Stefano Castelvecchi. Edited by Stefano Castelvecchi. University of Chicago Press.

Boyle, Matthew L. C. 2024. “The Serenade Topic, the Serenade Construction, and the Creation of Amorous Sweetness in ottocento Opera.” Journal of Music Theory 68/1: 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-10974683

Boyle, Matthew L. C. 2025a. “Rossinian Reiz: Strategic Musical Irritation and the Capturing of Attention.” Music Theory Spectrum 47 (2). https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtae028

Boyle, Matthew L. C. 2025b. “Reading Mozart’s Rondòs.” In Analyzing Mozart’s Operas, 159–215. Edited by Lauri Suurpää, Nathan John Martin, and John Koslovsky. Peeters Publishers.

Budden, Julian. 1979. The Operas of Verdi 2: From Il Trovatore to La Forza del destino. Oxford University Press.

Bourcard, Francesco de. 1858. Usi e costumi di napoli e contorni descritti e dipinti, vol. 2. G. Naples: Nobile.

Burney, Charles. 1773. The Present State of Music in France and Italy, 2nd edition. London.

Calaresu, Melissa. 2013. “Collecting Neapolitans: The Representation of Street Life in Late Eighteenth-Century Naples.” In New Approaches to Naples c. 1500–1800, 176–202. Edited by Melissa Calaresu and Helen Hills. Routledge.

Calaresu, Melissa and Danielle van den Heuvel. 2016. “Introduction: Food Hawkers from Representation to Reality.” In Food Hawkers: Selling in the Streets from Antiquity to the Present, 1–18. Edited by Melissa Calaresu and Danielle van den Heuvel. Routledge.

Cohn, Richard. 1996. “Maximally Smooth Cycles, Hexatonic Systems, and the Analysis of Late-Romantic Triadic Progressions.” Music Analysis 15, no. 1 (March): 9–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/854168

Cottrau, Guglielmo. 1865. Passatempi musicali raccolta complete delle canzoni Napoletane composte di Guglielmo Cottrau. Naples: Regio Stabilimento Musicale di Teodoro Cottrau. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12113/2964

Coward, David, trans. 2003. The Figaro Trilogy. Oxford University Press.

Deasy, Martin. 2008. “Local Color: Donizetti’s Il furioso in Naples.” 19th-Century Music 32 (1): 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1525/ncm.2008.32.1.003

Decker, Gergory J. and Matthew R. Shaftel, ed. 2020. Singing in Signs: New Semiotic Explorations of Opera. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190620622.001.0001

De Simone, Roberto, ed. 1979a. La tradizione in Capania, EMI 3C 164–18431/37, 33 1/3 rpm (7 LPs).

De Simone, Roberto. 1979b. Canti e tradizioni popolari in Capania. Giuseppe Vettori, Rome: Lato Side.

Duke, Craig. 2021. “Lyric Forms as ‘Performed’ Speech in Das Rheingold and Die Walküre: A Study of Operatic Convention in Wagnerian Music Drama.” Journal of Music Theory 65/2: 287–323. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-9143204

Edgecombe, Rodney Stenning. 2016. “Figaro’s aria di sortita in Il barbiere di Siviglia.” The Musical Times 157, no. 1935 (Summer): 57–68.

Gleichmann, J. A. 1830. “Bemerkungen über den behaupteten climatischen Einfluss auf die menschlichen Stimmen.” Cäcilia XI (41): 169–82.

Goehring, Edmund J. 2004. Three Modes of Perception in Mozart: The Philosophical, Pastoral, and Comic in Così fan tutte. Cambridge Studies in Opera. Cambridge University Press.

Hatten, Robert. 1994. Musical Meaning in Beethoven: Markedness, Correlation, and Interpretation. Indiana University Press.

Hatten, Robert. 2004. Interpreting Musical Gestures, Topics, and Tropes: Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert. Indiana University Press.

Hunter, Mary. 1999. The Culture of opera buffa in Mozart’s Vienna: A Poetics of Entertainment. Princeton University Press.

Hunter, Mary. 2014. “Topics and Opera Buffa,” In The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, edited by Danuta Mirka, 61–89. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199841578.013.003

Johnson, Janet. 2004. “Il barbiere di Siviglia.” In The Cambridge Companion to Rossini, edited by Emanuele Senici, 159–174. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL9780521807364.012

Johnson, N. F. Byng. 1919. “A Musical Street Cry.” The Musical Times 60, no. 919 (September): 494. https://doi.org/10.2307/3701983

Krug, S. 1829. “Der climatische Einfluss auf die menschlichen Stimmen: Parallelen zwischen Deutschland und Italien.” Cäcilia XI (41): 1–14.

Lamacchia, Saverio. 2008. Il vero Figaro o sial il falso factotoum: Riesame del “Barbiere” di Rossini. EDT.

Lamacchia, Saverio. 2019. “Towards a New Interpretation of Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia.” In Zwischen Revolution und Bürgerlichkeit, edited by Isolde Schmid-Reiter and Dominique Meyer, 93–109. ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft.

Larson, Steve. 2012. Musical Forces: Motion, Metaphor, and Meaning in Music. Indiana University Press.

Lichtenthal, Peter. 1836. Dizionario e Bibliografia della Musica. Milan: Antonio Fontana.

Lindström, Carlo. 1836. Costumi, e vestiture napolitana, disegnati ed incise da Carlo Lindström. Naples.

Link, Dorothea. 2008. “The Fandango Scene in Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association133 (1): 69–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrma/fkm011

Maniates, Maria Rika and Richard Freedman. 2001. “Street Cries.” Grove Music Online.https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.26931

Markstrom, Kurt. 2007. The Operas of Leonardo Vinci, Napoletano. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press.

Marx, Adolf Bernhard. 1826. Die Kunst des Gesanges, theoretich-praktisch. Berlin: Schlesinger.

Mirka, Danuta. 2014. “Introduction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Topic Theory, edited by Danuta Mirka, 1–60. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199841578.013.002

Moe, Nelson. 2002. The View from Vesuvius: Italian Culture and the Southern Question. University of California Press.

Montesquieu, Charles de Secondat. 1777. The Spirit of the Laws, vol. 1 in The Complete Works of M. de Montesquieu. London: T. Evans. http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/montesquieu-complete-works-vol-1-the-spirit-of-laws

Moreen, Robert. 1975. “Integration of Text Forms and Musical Forms in Verdi’s Early Operas.” PhD dissertation, Princeton University.

Pinelli, Bartolomeo. 1817. Raccolta di cinquanta costume li più interessanti delle città, terre, e paesi, in provincie diverse del regno di Napoli. Rome: Presso Giovanni Scudellari.

Platoff, John. 1990. “The buffa aria in Mozart’s Vienna.” Cambridge Opera Journal 2, no. 2 (July): 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954586700003177

Poriss, Hilary. 2022. Gioachino Rossini’s The Barber of Seville. Oxford University Press.

Privitera, Massimo. 2023. “Naples, City of Sounds: Representing the Phonosphere of a Romantic Capital.” Music, Place, and Identity in Italian Urban Soundscapes circa 1550–1860, 241–65. Edited by Franco Piperno, Simone Caputo, and Emanuele Senici. Routledge.

Ratner, Leonard G. 1980. Classic Music: Expression, Form, and Style. Schirmer Books.

Ricci, Federico. [after 1853]. Gridi de’ venditori di Napoli, raccolte da Federico Ricci. Naples: Teodor Cottrau. http://digitale.bnnonline.it/index.php?it/149/ricerca-contenuti-digitali/show/8/

Robinson, Paul A. 1985. Opera and Ideas: From Mozart to Strauss. Cornell University Press.

Rossini, Gioachino. (1816) 1993. Il barbiere di Siviglia: Facsimile dell’autografo. Edited by Philip Gossett. Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia.

Rothstein, William. 2008. “Common-tone Tonality in Italian Romantic Opera: An Introduction.” Music Theory Online14, no. 1 (March). http://doi.org/10.30535/mto.14.1.3

Rothstein, William. 2023. The Musical Language of Italian Opera: 1813–1859. Oxford University Press.

Sánchez-Kisielewska, Olga. 2016. “Interactions between Topics and Schemata: The Case of the Sacred Romanesca.” Theory and Practice 41: 47–80.

Sánchez-Kisielewska, Olga. 2023. “On Figaro’s Alleged Minuet and Some Challenges and Opportunities of Topic Theory.” Music Theory Spectrum 45 (1): 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtac027

Senici, Emanuele. 2019. Music in the Present Tense: Rossini’s Italian Operas in Their Time. University of Chicago Press.

Sievers, Georg Ludwig Peter. 1829. “Der Einfluss des römischen Climas auf die Gesangfähigkeit.” Cäcilia XI (43): 209–17.

Sherrill, Paul. “The Metastasian Da Capo Aria: Moral Philosophy, Characteristic Actions, and Dialogic Form.” PhD dissertation, Indiana University.

Stendhal. 1957. Life of Rossini. Translated by Richard N. Coe. Criterion Books.

Stroud, Cara. 2021. “Webs of Meaning in John Corigliano’s Tarantellas.” Music Theory Spectrum 43 (2): 246–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/mts/mtaa029

Taruskin, Richard. 2005. Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford University Press.

Verdi, Giuseppe. (1869) 1904. La forza del destino (Melodramma in four acts), libretto by Francesco Maria Piave. G. Ricordi.

Weiner, Marc A. 1995. Richard Wagner and the Anti-Semitic Imagination. University of Nebraska Press.

Zbikowski, Lawrence M. 2003. Conceptualizing Music: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis. Oxford University Press.

Notes

- See Lamacchia (2008, 112–13; 2019) for interpretations of Figaro as an ancillary character within the opera.

- This side of Figaro is most readily seen in the famous trio from Act 2 of Barbiere, where he interrupts Rosina and Almaviva’s would-be duet “Ah qual colpo inaspettato,” seemingly aware of the temporal absurdity that slow-movement encounters stage in dramatic time, an interpretation described by Johnson (2004, 167–170). For an overview of dramatic interpretations of Rossini’s Figaro, see Senici (2019, 103–115). Edmund Goehring (2004) similarly finds Don Alfonso to operate “outside of the operatic conventions that regulate the other characters” (113).

- When Figaro’s guitar is used in the Count’s diegetic serenade “Saper bramte,” his instrument is played by the Count as Figaro hides under Rosina’s window. The opera’s most overt Spanish number, the second act “Seghidiglia spagnola” is sung by Bartolo.

- The Count, in contrast, received a Spanish-inflected canzone in Act 1, accompanied by guitar, which was sung and played on guitar by the Spanish-born tenor Manuel García (Rossini 1816 [1993], 22). There was also an impulse in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to ascribe a Spanish character to Figaro’s music in this opera. Most famously, commentators like the early Rossini musicologist Giuseppe Radiciotti speculated that there once was a lost overture to the opera that used Spanish themes provided by García. No documentary evidence exists to support this theory (Rossini 1816 [1993], 24).

- As in this essay, topical analysis has long centered issues of stylistic register and its musical representations of social status, class, and gender. My use of musical topics in this essay are most indebted to Leonard Ratner (1980), Wye Allanbrook (1983), Robert Hatten (1994, 2004), and Mary Hunter (1999). In particular, I try to emulate Allanbrook’s and Hatten’s attention to how musical gestures could create musical meaning.

- An important source for these stereotyped tropes was the Baron of Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws (1777) which attributed bodily difference to regional climates (Moe 2002, esp. 13–36). Similar ideas persisted in nineteenth-century music criticism. See Gleichmann (1830), Krug (1829), Marx (1826, esp. 192–199), and Sievers (1829).

- Martin Deasy (2008) discusses a more overt operatic depiction of lazzaroni characters in Donizetti’s Il furioso. He notes that for a production of Il furioso for Naples’s Teatro Nuovo, the character Kaidamà “has effectively become a Neapolitan beggar” (17). Furthermore, Deasy points out that “Naples had achieved widespread notoriety for its squalor and overcrowded conditions. Packed into the medieval city center in condition of extreme poverty, many of its 400,000 inhabitants were forced to live rough in the streets, surviving through menial work or begging” (17).

- See Calaresu 2013 for more on this iconographic phenomenon.

- Similar items depicting the urban poor were also for sale in other large urban areas such as Milan, New York, London, and Paris (Calaresu and van den Heuvel 2016, 7). See also Pritivera 2023 (247): “Grand Tourists were fascinated by [the cries of hawkers], and many painters and engravers chose them as subjects for their works.”

- Privitera cites De Simone (1979a and 1979b) as potential models to help readers imagine this component of the lost “phonosphere” of Romantic Naples.

- Kurt Markstrom (2007, 31–32) has identified Ciccariell’s “Vorria reentare sorecillo” from Leonardo Vinci’s Li zite ‘ngalera as an example of a Neapolitan street song with a colasione-like accompaniment incorporated into opera. Markstrom also identified the opening number from Michelangelo Faggioli’s La Cilla (1706), “Songo le Forentane” from Vinci’s Lo Scassone (1720), “Mentre l’erbetta” from Giovanni battista Pergolesi’s Il Flaminio (1735), and “Passo ninno da ccà” from Pergolesi’s Lo frate ‘nnamorato (1732) as other early examples Neapolitan folk-infused operatic numbers.

- Rossini’s own perspective would have been aligned with the Italian North. Born in the Adriatic city of Pesaro, just 30 kilometers south of the North-South dividing La Spezia-Rimini isogloss, his early operatic career was centered in major northern cities like Venice and Milan. Rossini only ventured as far south as Naples and Rome in 1815, mere months before composing this opera (Rossini [1816] 1993, 4–5).

- These are topics in the strictest sense put forth by Danuta Mirka as “styles and genres taken out of their proper context and used in another one” (Mirka 2014, 2).

- See Zbikowski (2003, 63–95), Hatten (2004, 100–101), and Larson (2012, 20–21, 46–51) for more on the interpretation of cross-domain mappings and musical analogy/metaphor.

- I describe a similar web of meanings generated by the serenade, a genre also associated with the Mediterranean basin by examining the affective associations of its defining features (Boyle 2024).

- Although their ternary formal readings are quite similar, Lamacchia (2008, 195n57) is uncomfortable with Taruskin’s (2005, 3:23) anachronistic description of the form of “Largo al factotum” as a “typical da capo aria.” My understanding of patter arias is indebted to John Platoff’s (1990) description of the genre.

- Platoff (1990) interpreted such tonic and dominant thematic groups to be the “musical paragraphs” of an “exposition” in the Classical sense (106n25).

- Although Platoff (1990) defines these in terms of how quickly lines of poetry are delivered over a set number of measures, as seen in his Example 1 (104), the acceleration of Figaro’s patter in mm. 237–253 is created not by the rate of declamation but instead by accelerating the internal pacing of the melody. Each syllable in the “second-order” patter is more likely to articulate a unique note than in the initial patter of mm. 163–236, which often would repeat notes within groups of three.

- In Giuseppe Verdi’s later nineteenth-century practice, Robert Moreen (1975) found that the “completion of [an aria’s] sense” (45)—the final coalescing of its central meaning—was often coordinated with final cadences. In presenting diatonic, cadential progressions together with this meaning-clarifying text, Rossini rhetorically presents those phrases in the guise of a classical buffa aria envoi. Similar coordination of poetic meaning with end-accented cadences appears in many operatic practices, ranging from eighteenth-century da capo arias (Sherrill 2016), two-tempo rondòs (Boyle 2025b), and even the formal processes of Richard Wagner’s music dramas (Duke 2021).

- Stroud (2021) provides a similar list of “standard features associated with tarantella dances” in her Example 1 (248). More generally, nonsense syllables and unorthodox chromaticism were hallmarks of Rossini’s compositional style and often received negative attention from contemporary critics as crude and disruptive, which I discuss in Boyle (2025a).

- For example, the three songs labelled as tarantellas in the mid-century Passatempi musicali (1865), a collection of Neapolitan songs transcribed and composed by Guglielmo Cottrau, are in a fast a $$^{6}_{8}$$ meter with a minor tonality.

- The tarantellas from Passatempi musicali (Nos. 43, 73, and 89), for instance, emphasize phrases that begin with a vocal-melodic anacrusis as does Rossini’s vocal tarantella “La danza.” This rhythmic profile also starkly contrasts with the prominent downbeat orientation of the opening phrase of “Largo al factotum” (Example 2), which initiates a section significantly less suggestive of the tarantella topic.

- When travelling through Apulia, Burney (1773), for instance, questioned this origin of the dance: “[It is] so thoroughly believed by some innocent people in the country, that when really bitten by other insects, or animals that are poisonous, they take this method of dancing, to a particular tune, till they sweat; which, together with their faith, sometimes makes them whole. They will continue the dance, in a kind of frenzy, for many hours, even till they drop down with fatigue and lassitude” (323–325).

- Although the “B” section begins in G major, over its course, as discussed below, it succumbs to ever-increasing minor-mode elements, culminating in a harmonic “crisis.” The thematic material first stated in G major quickly appears in the modally borrowed key of E-flat major. By the section’s conclusion, G major is reinterpreted as the dominant of the aria’s minor tonic (C minor).

- The chromatic thirds-related harmonies of tarantellas like “Largo al factotum” may also have been associated with Southern Italian vernacular music by listeners in the decades around 1800. Burney, for instance, remarked on the frantically chromatic harmonic language of Mezzogiorno street musicians within his Italian travelogue (1773). One autumn encounter in Naples prompted a detailed account of both instrumental forces and harmonic language: “In the canzone of to-night they began in A natural, and, without well knowing how, they got into the most extraneous keys it is possible to imagine, yet without offending the ear…It is a very singular species of music, as wild in modulation, and as different from that of all the rest of Europe as the Scots, and is, perhaps, as ancient, being among the common people merely tradition” (321–322). His fascination with this performance had Burney request a transcription from the head musician. The performance heard by Burney gradually expanded outward from a central tonic A within this space, first only to adjacent nodes and eventually venturing to even more remote areas, and, as Burney emphasized, this A tonality continued to return, although probably in ways that elude standard contrapuntal explanation.

- Similar nonsense syllables (“la, la, ra, la, la, la, la, la, ra, la”) also appear in the poetic text of the comic aria “Più bel mestiere del parrucchiere” from Valentino Fioravanti’s Matrimonio per susurro (Lisbon 1803, Rome 1811), which might have served as a model for Figaro’s cavatina (Lamacchia 2008, 117, 193).

- Rodney Edgecombe (2016) presents multiple topical interpretations of this passage, including those of a “postilion’s song, of an aria da caccia, of a sennet, of a tarantella, and of a marche guerrière” (58).

- William Rothstein (2023) finds that in Barbiere di Siviglia “surprise and cartoonish rage are so often expressed by sudden moves, usually marked forte or fortissimo, to triads well to the flat side of the local key. These triads are usually chromatic mediants” (205).

- William Rothstein (2008, par. 27) has identified this passage as a prolongation of the tonic C through a downward triadic progression by major thirds.

- Although the passage outlines an implied chain of 7–6 suspensions, usually emblematic of higher stylistic registers, Rossini’s gestural language and the libretto’s dramatic context undercut potential resonances with more serious styles.

- Note that the piano part of this transcription is not intended as a faithful recreation of a vendor’s cry, rather it was an added convenience for “being sung and played in a bourgeois or aristocrat home with a piano” (Privitera 2023, 249).

- The vocal texture in Dulcamara’s cavatina “Udite, udite, o rustici” from Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore (1832) hovers between the hawked cries of a street vendor and more standard comic patter. In Verdi’s La forza del destino, another street-cry vocal texture is used by the peddler (rivendugliolo) Trabuco in his act 3, scene 11 arietta “A buon marcato chi vuol comprare.” Trabuco hawks “various objects of meagre value” by singing in a rough manner, in imitation of street vendor cries (Verdi [1869] 1904, 425).

- Most notably, Rossini indicated that Isacco’s highly intoned Ds should be performed nasale, explicitly drawing on European tropes of Jewish bodily difference. Marc Weiner identified such nasality as a central antisemitic vocal trope in nineteenth-century music (Weiner 1995, esp. 117–150).

- Incidentally, Julian Budden (1979) described Trabuco as clearly Jewish in how it imitates the sound world of Isacco’s cavatina: “Trabuco’s solo…has a more immediate ancestor in the entrance of Isacco in La Gazza Ladra… We hardly need Verdi’s marking of Ebreo to tell us that he conceived this as a Jewish character-part” (2:497–498).