David S. Carter

Abstract

Prior scholarship has engaged with teleology in popular song as it is manifested in buildup introductions, verse-prechorus-chorus cycles, and EDM-inspired builds. Yet teleology in bridges—especially the textural accumulations following breakdowns that I call here rebuilds—has received much less attention. In this article, I present an empirically-based model of bridge-quality rebuilds, examining 118 songs that either repurpose previously presented melodies to make bridge blends or use new material and build energy towards an arrival. I particularly highlight the approach of building with insistent repetition of a new vocal line over a harmonic loop, what I term a repeating-phrase rebuild. I conclude by making some observations regarding apparent changes to rebuilds over time, finding in the 118 songs a seeming trend away from instrumental and verse-based rebuilds towards the use of new material and repeating-phrase rebuilds.

View PDF

Return to Volume 38

Keywords and Phrases: popular music; form; bridge; teleology; climax; blend; texture

Introduction

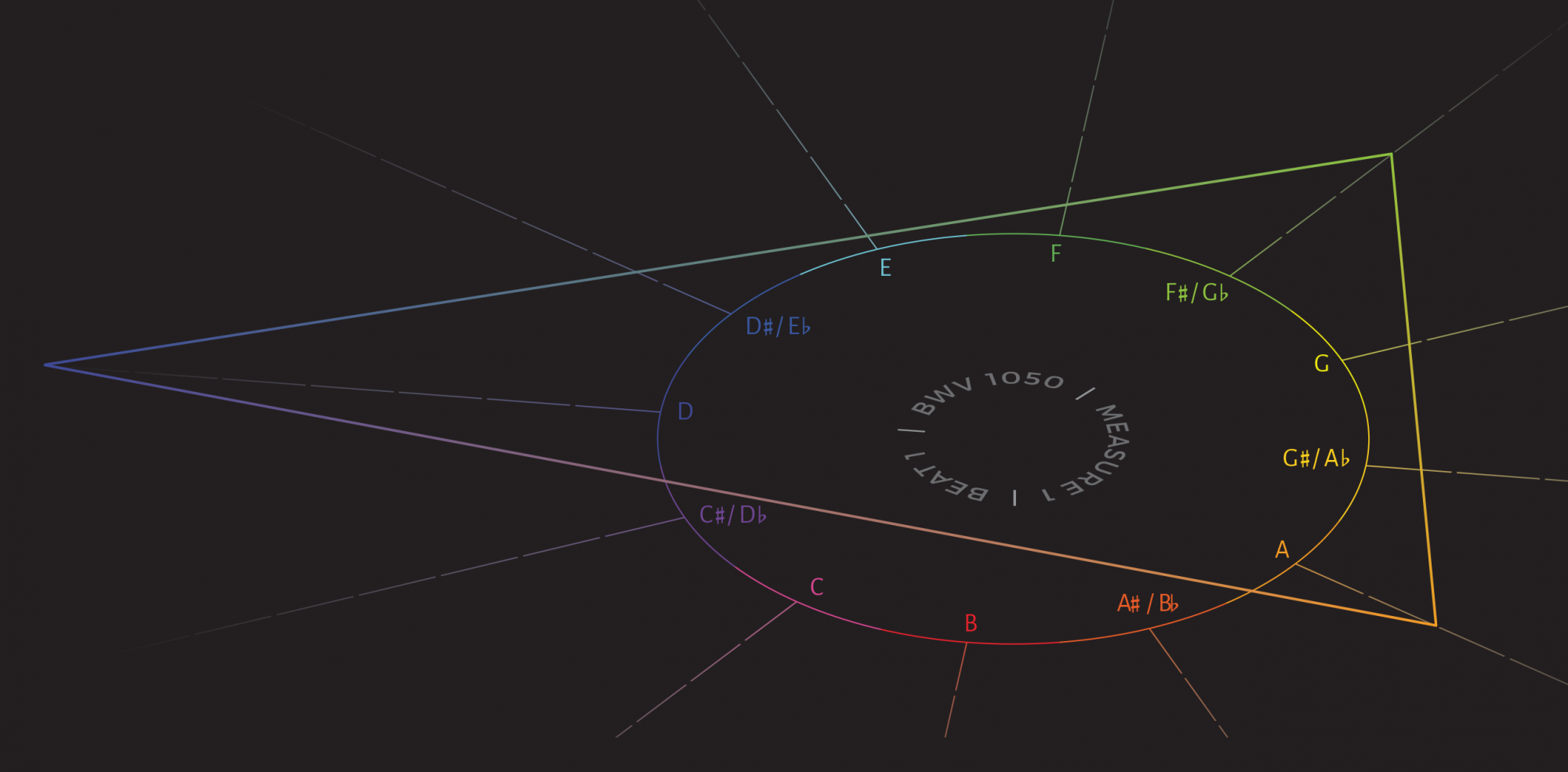

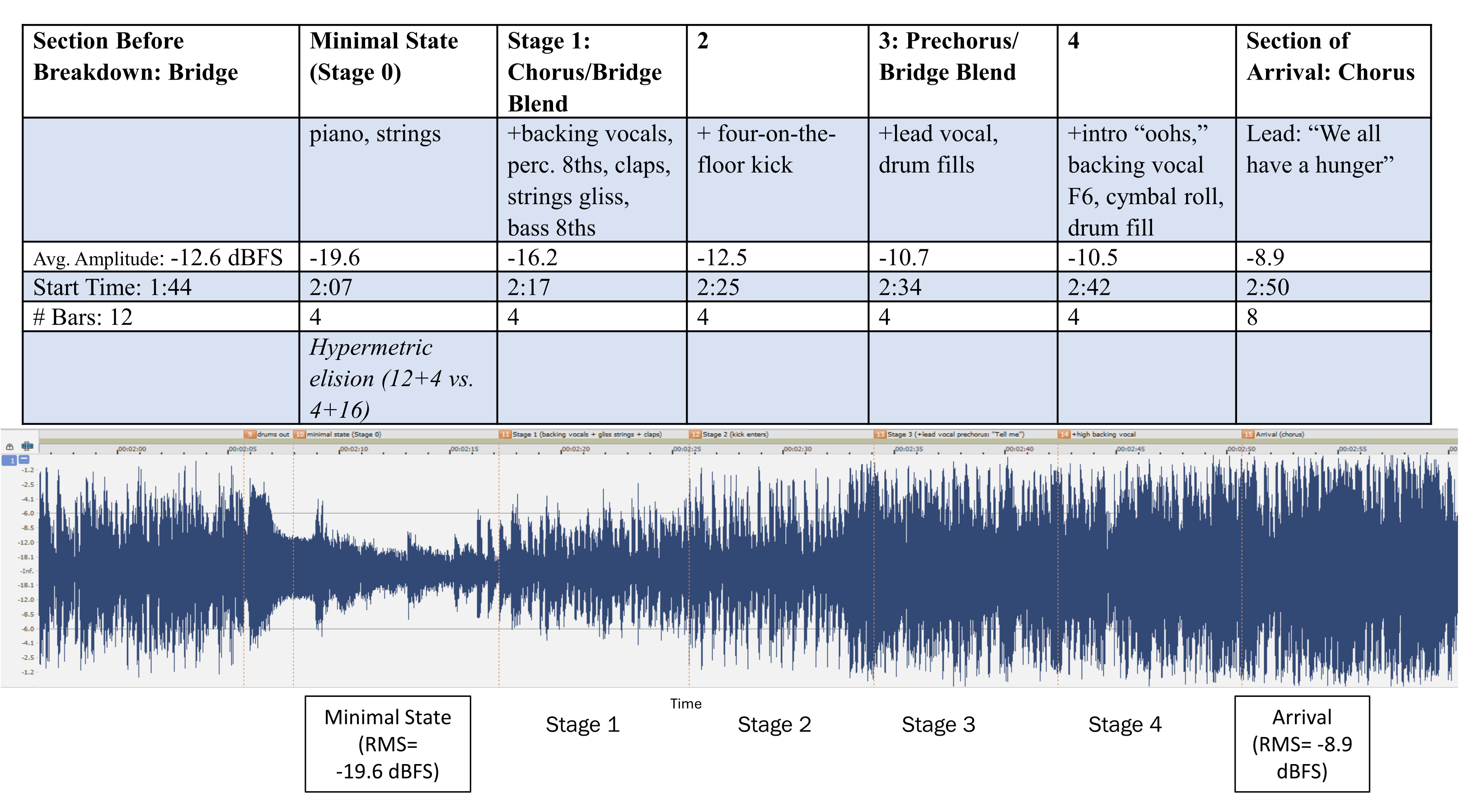

In Florence + the Machine’s “Hunger” (2018; Example 1), the vocal bridge is followed not by an immediate return to the song’s chorus, but instead by a dramatic breakdown. The piano, drums, and bass come to a halt at 2:04 and by 2:07 their sound has died out. Lead vocalist Florence Welch quietly sings of “staring at your phone,” accompanied by sustained strings and piano chords on the downbeats. And rather than abruptly returning to a full texture at this point, a gradual rebuilding process begins. It starts with a loop of the ghostly, nearly monotone backing vocals previously heard in the second chorus (“We all have a hunger”), the repeating lyric seeming to reflect the teleological yearning of the music. This return of previous chorus material in the bridge position of the song makes for a chorus-bridge blend (de Clercq 2012, 235–237), with the glissandi in the sighing strings furthering the sense of instability by stretching outside of equal temperament. A second stage of rebuilding, starting at 2:25, introduces a four-on-the-floor kick drum. The third stage, propelled by an ascending bass line, repurposes the previously heard prechorus (“Tell me what you need …”) to build tension. A final stage, starting at 2:42, brings back the “oohs” from the song’s intro as well as a sustained high vocal F6, climactically combining previous elements of the song in a manner reminiscent of Lavengood’s “cumulative chorus” (2021, 5:55–7:04).1 A new dynamic peak is reached at 2:50, marking the moment of arrival. This arrival is at last a return to a full-textured chorus, characterized by a call and response between the lead and backing vocals alternating assertions of “We all have a hunger.”

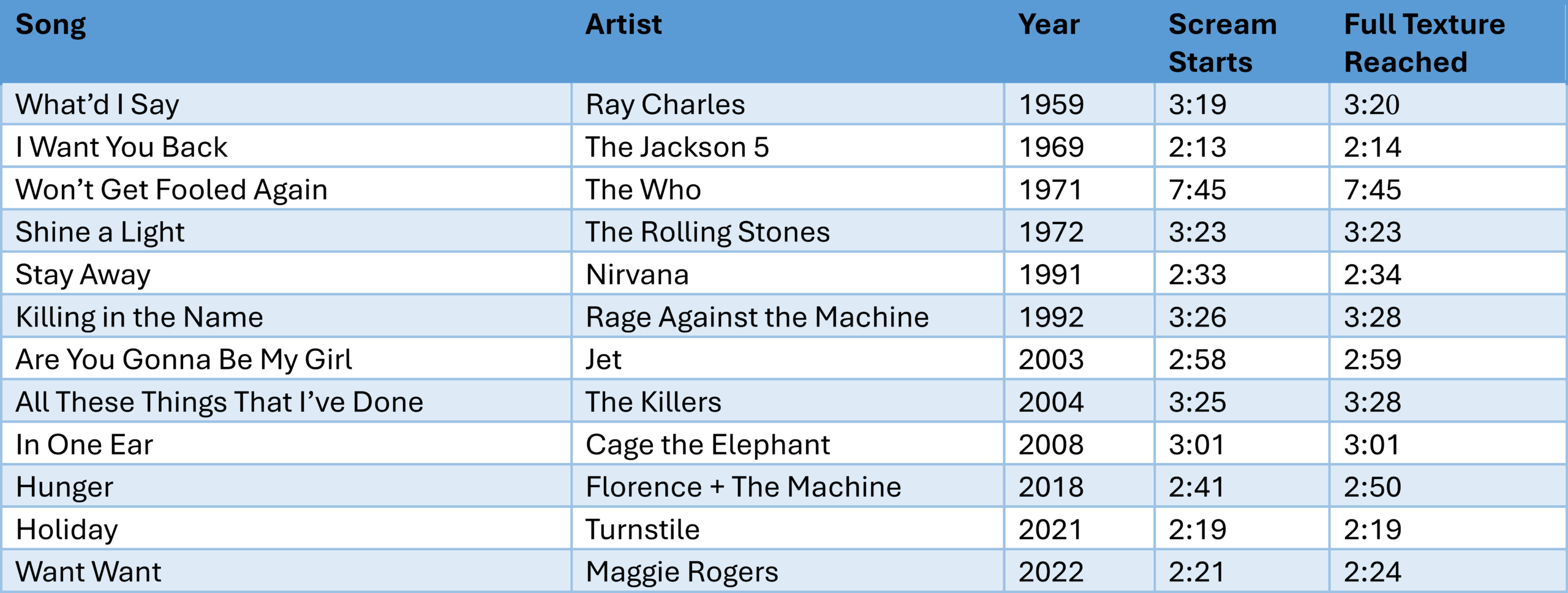

The breakdown and rebuild in “Hunger” is a dramatic example of an approach that goes back at least to Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say” in 1959: a breakdown in the bridge position of a song is followed by a gradual rebuilding of texture, leading to the recording’s climax. Popular music scholars have discussed the teleology of buildup introductions at the starts of songs (Spicer 2004; Attas 2015) as well as that of verse-prechorus-chorus successions (Nobile 2022) and that of the EDM-style builds and drops that have made their way into mainstream pop in the twenty-first century (see Osborn 2023; Stroud 2022; Adams 2019; and Peres 2016, among others). But the teleology of bridge sections—particularly where there is a breakdown and a gradual rebuilding of texture, what I here call a rebuild—has received relatively little scholarly attention, despite its longstanding importance in popular music.2 The use of a bridge-quality rebuild with at least one intervening stage in between the minimal state and the arrival occurs fairly frequently in pop and rock, though most songs do not contain one.3 Most breakdowns do not gradually return to a full texture, but more or less abruptly make such a return. But breakdowns and rebuilds, when they do occur, often lead to the climactic point of the song. While scholars such as Osborn, Adams, and Peres have approached “risers” or “builds” as derived from EDM, rebuilds are part of a longer and larger legacy of buildups of texture in the bridge position of a recording, with that tradition stretching back to the 1960s and earlier.4 And while scholars have dated the start of an increased reliance on texture and timbre over harmony in popular music to the 1990s or the turn of the century (Nobile 2022, 3.1–3.2; Peres 2016, 2–4), the use of rebuilds in the 1950s, ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s is a manifestation of how texture was employed to build teleologically much before then. Rebuilds in studio-recorded pop songs connect with a long tradition in gospel, soul, and live popular music of breakdowns followed by gradual rebuilds in energy that lead to a climactic arrival. By studying rebuilds we can more clearly see the ways in which popular music throughout the rock era (both before the era of EDM-influenced pop and after) can be just as teleological as common-practice art music, at times relying in part on harmony but often relying more on texture and other parameters considered secondary in analysis of common-practice literature (Fink 2011, 184). The persistence of bridge teleology across the decades is a testament to its visceral power over listeners, with a teleological build occurring often with greater intensity in bridges than it does in more commonly studied prechoruses.5

Rebuilds are additionally important to examine closely because they frequently combine aspects of multiple formal roles. When positioned in the middle of a song after multiple core verse-chorus cycles, a breakdown-plus-rebuild has bridge “quality,” even if it re-uses material that has previously been heard in a prior section (de Clercq 2012, 71–72, 221).6 A rebuild can constitute the entire bridge of a song, it can encompass a part of the bridge (typically the end of it), or it can be part of a larger bridge complex, preceded by an instrumental section that also has bridge quality. Breakdowns can be formal blends of bridge quality and some other role previously established in the recording, like chorus or introduction (de Clercq 2012, 235–237; see also Osborn 2023, 48–49). The same can be true of rebuilds that follow these breakdowns, though rebuilds can alternatively use new material and thereby comprise a more straightforward bridge.

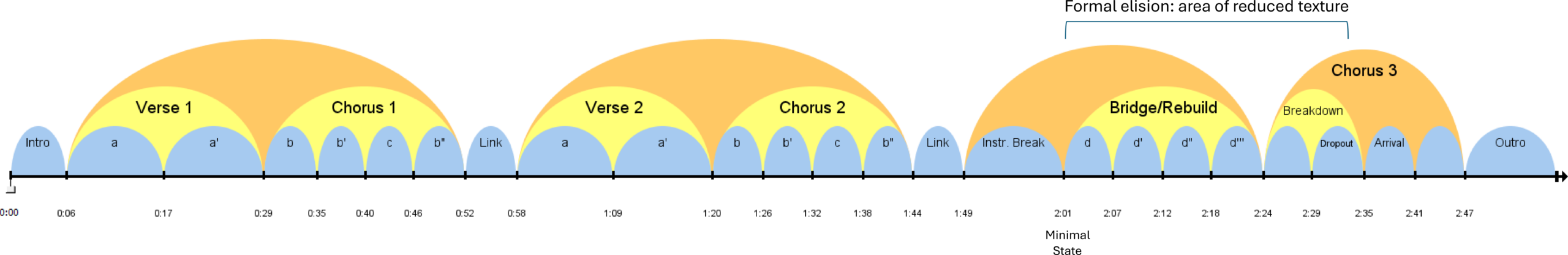

Figure 1 presents a model for a typical rebuild, illustrating how such a section is most commonly preceded by a second chorus, uses either chorus or new material for the increase in texture, and then is followed by another chorus. The start of the reduction is marked by the texture beginning to decrease, though in most cases the reduction is brief or immediate. This leads to the minimal state (stage 0), the point of the greatest reduction in texture. Once the minimal state has been reached, then the rebuild can begin. The starting rebuild material is the formal section that is the source for the music at the start of the minimal state; in “Hunger,” it is the chorus. Rebuilds, like that in “Hunger,” tend to be terraced and occur in stages, discrete increases in the texture from what has come immediately before.7 After one or more stages of rebuilding (typically one to five), the arrival is reached. In most instances, the arrival is a state of full texture and high energy, though there can be exceptions to this tendency.8 The section of arrival is the formal role that is the source for the music in the arrival, with this also being the chorus in “Hunger.” In sections 2 through 6 of this article, I will discuss the ways in which common aspects of rebuilds are manifested in specific songs.

1. Methodology

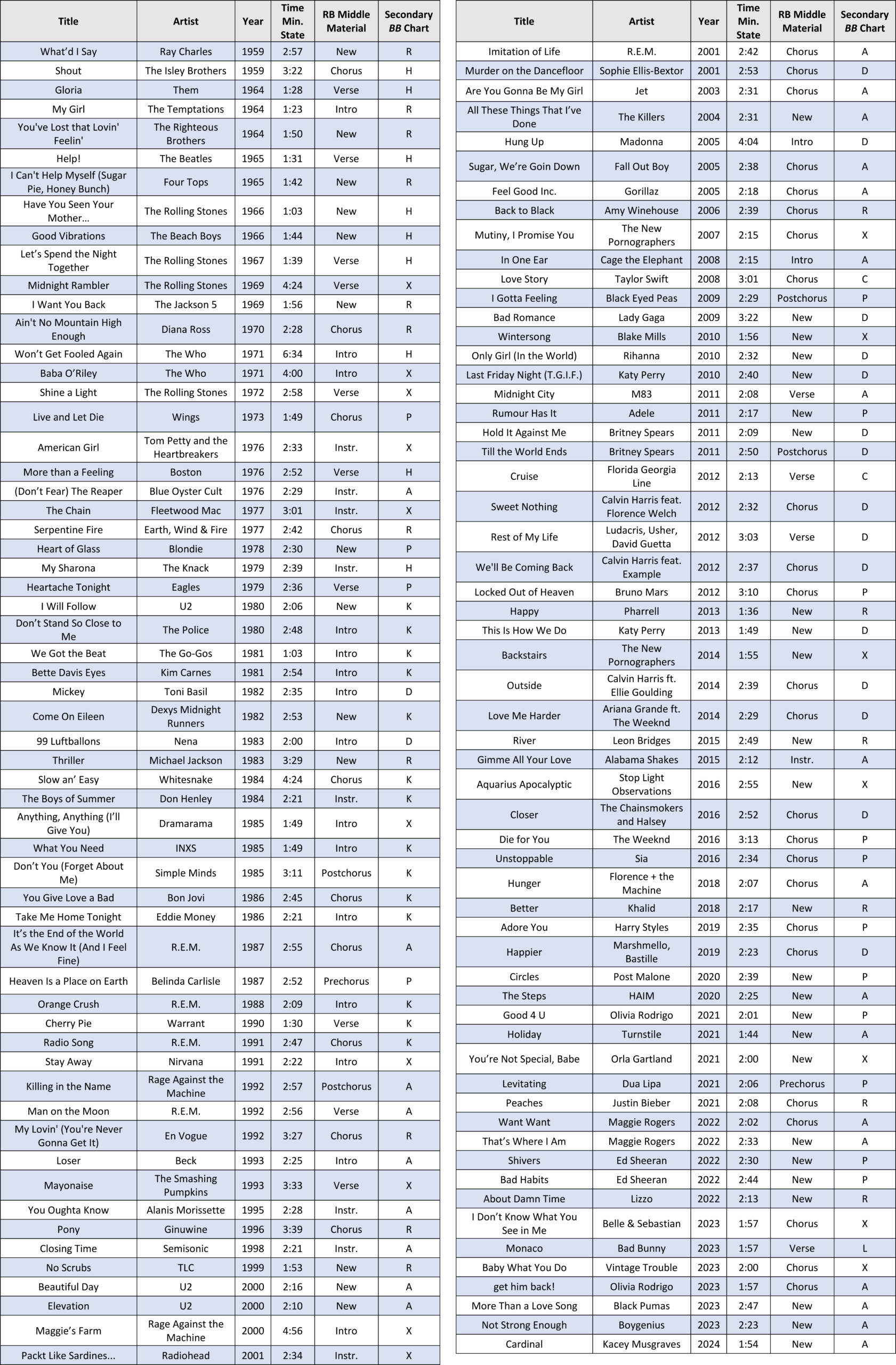

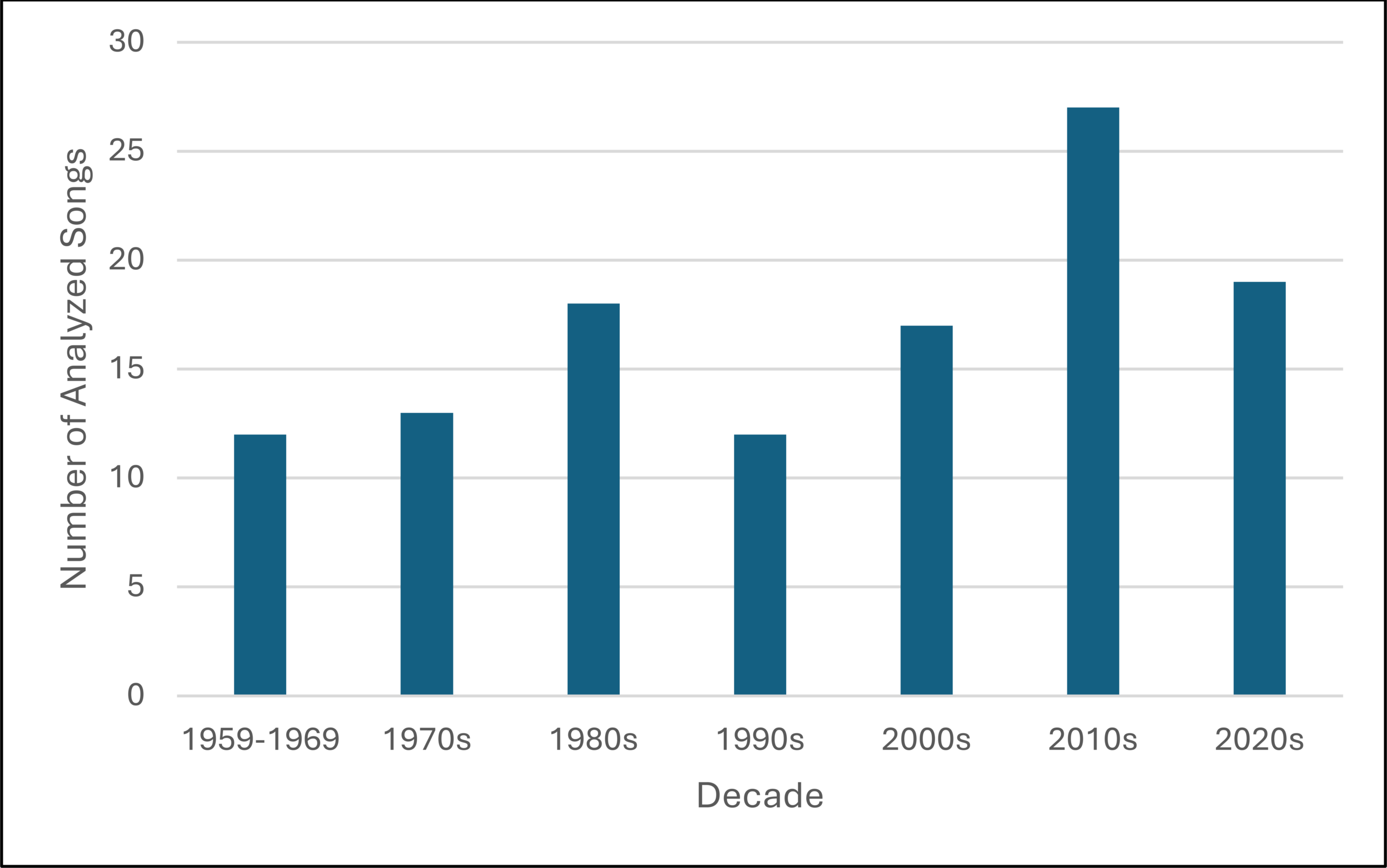

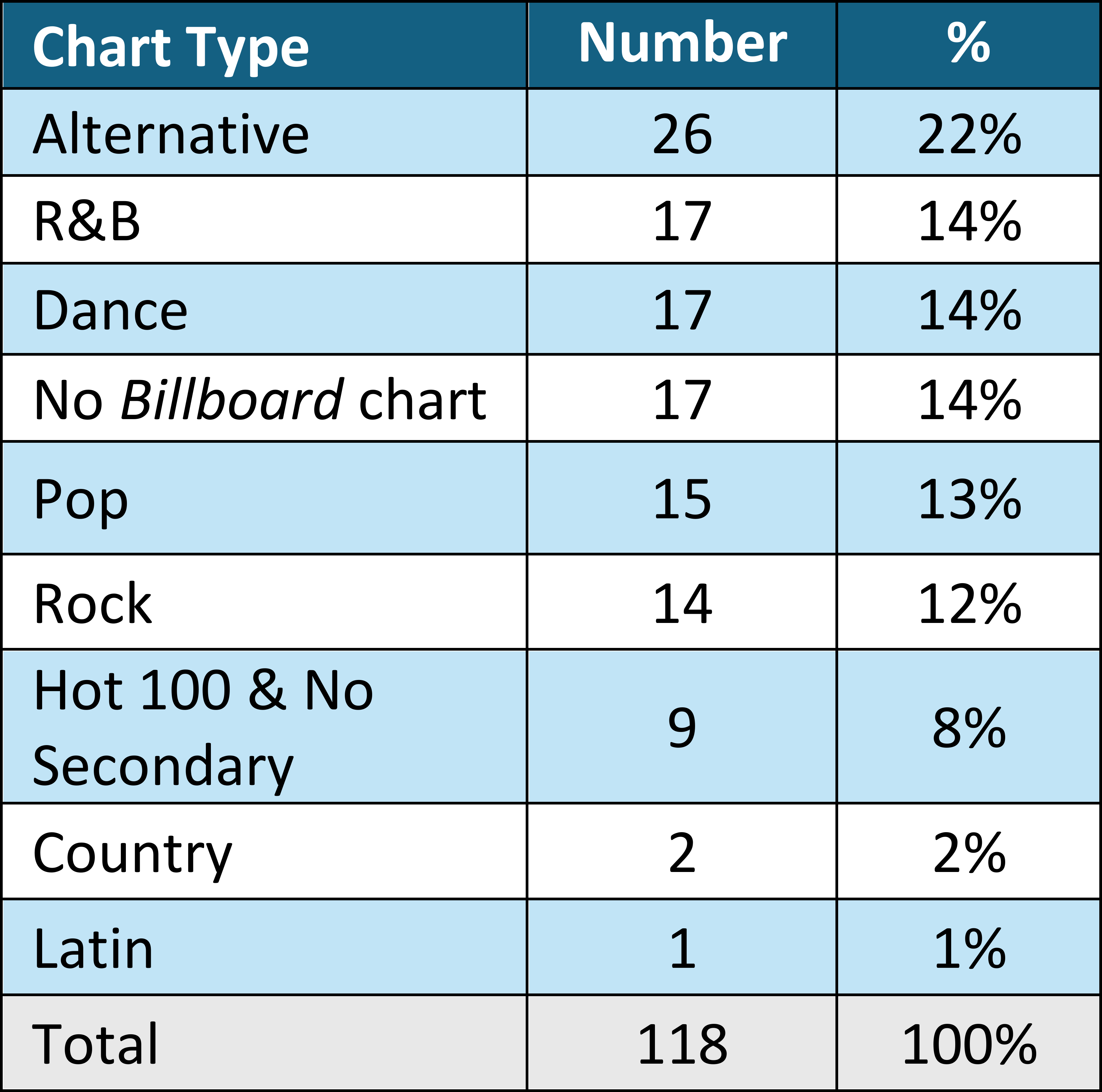

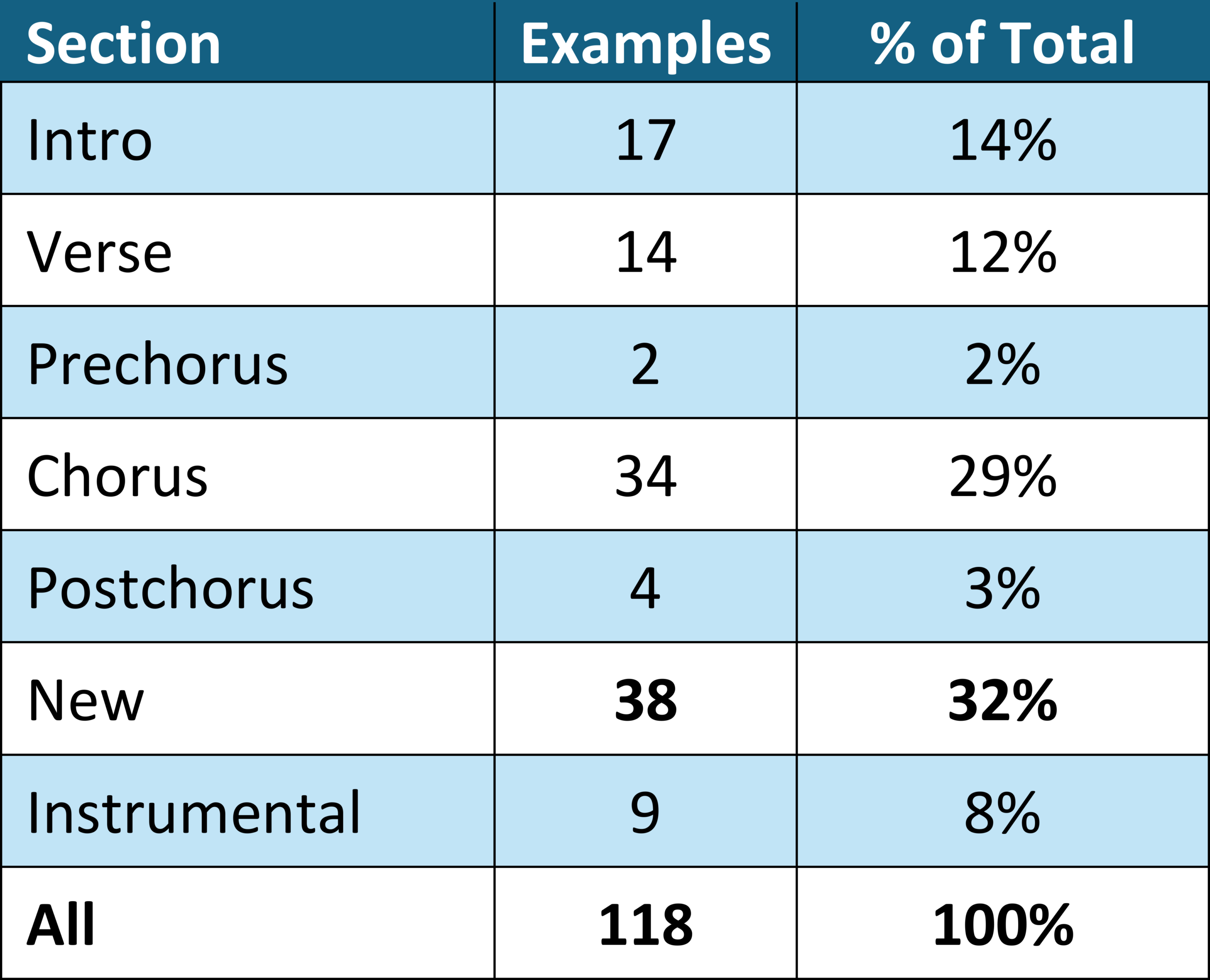

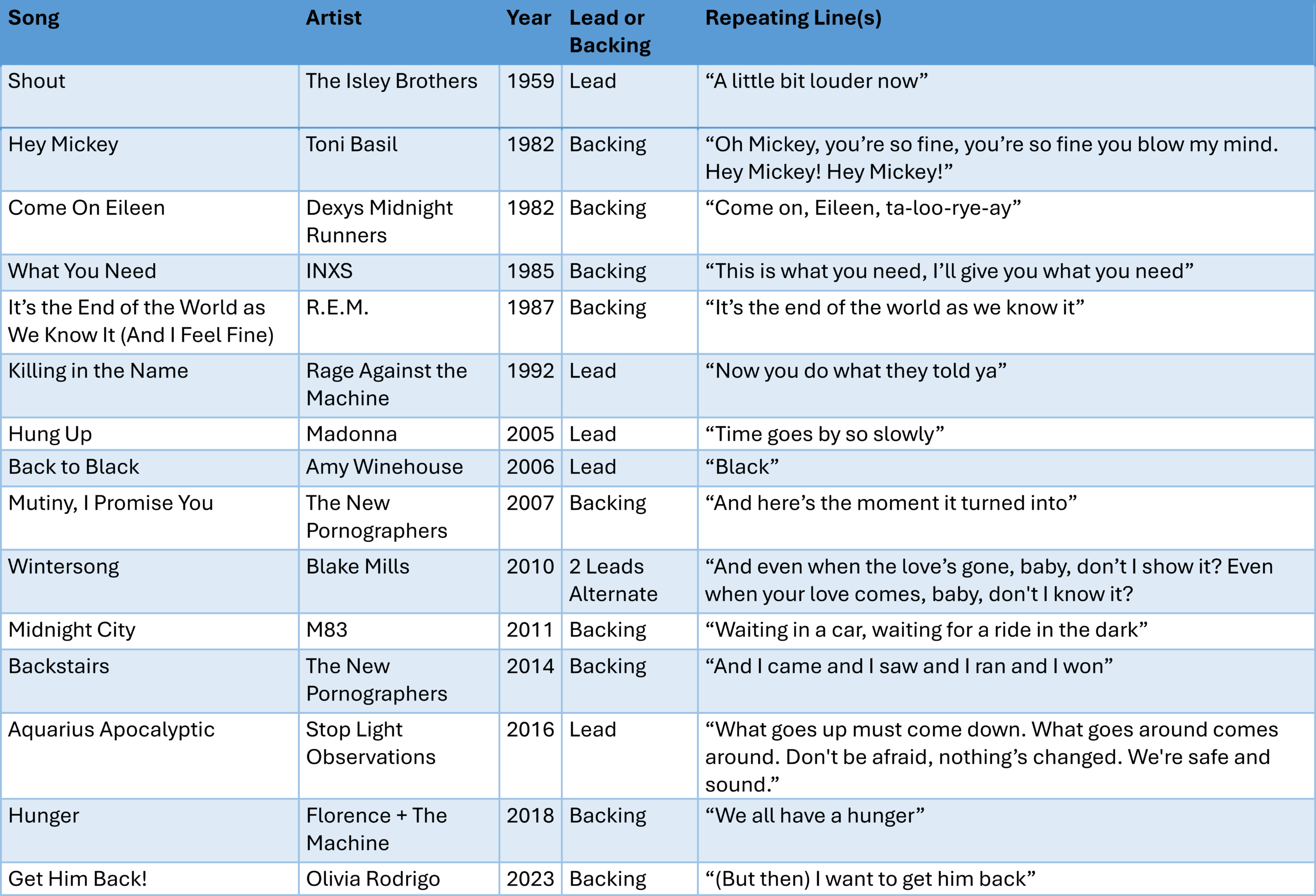

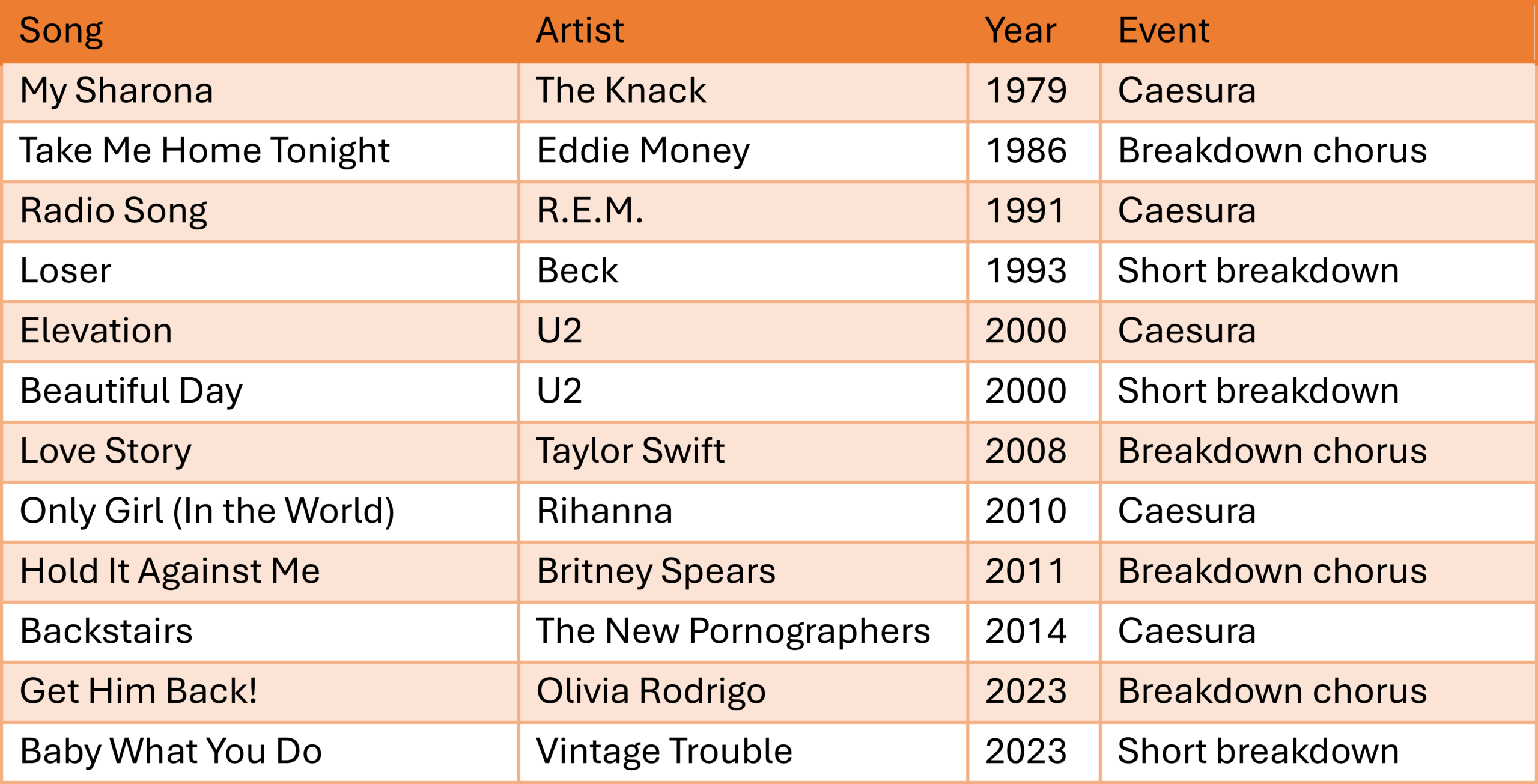

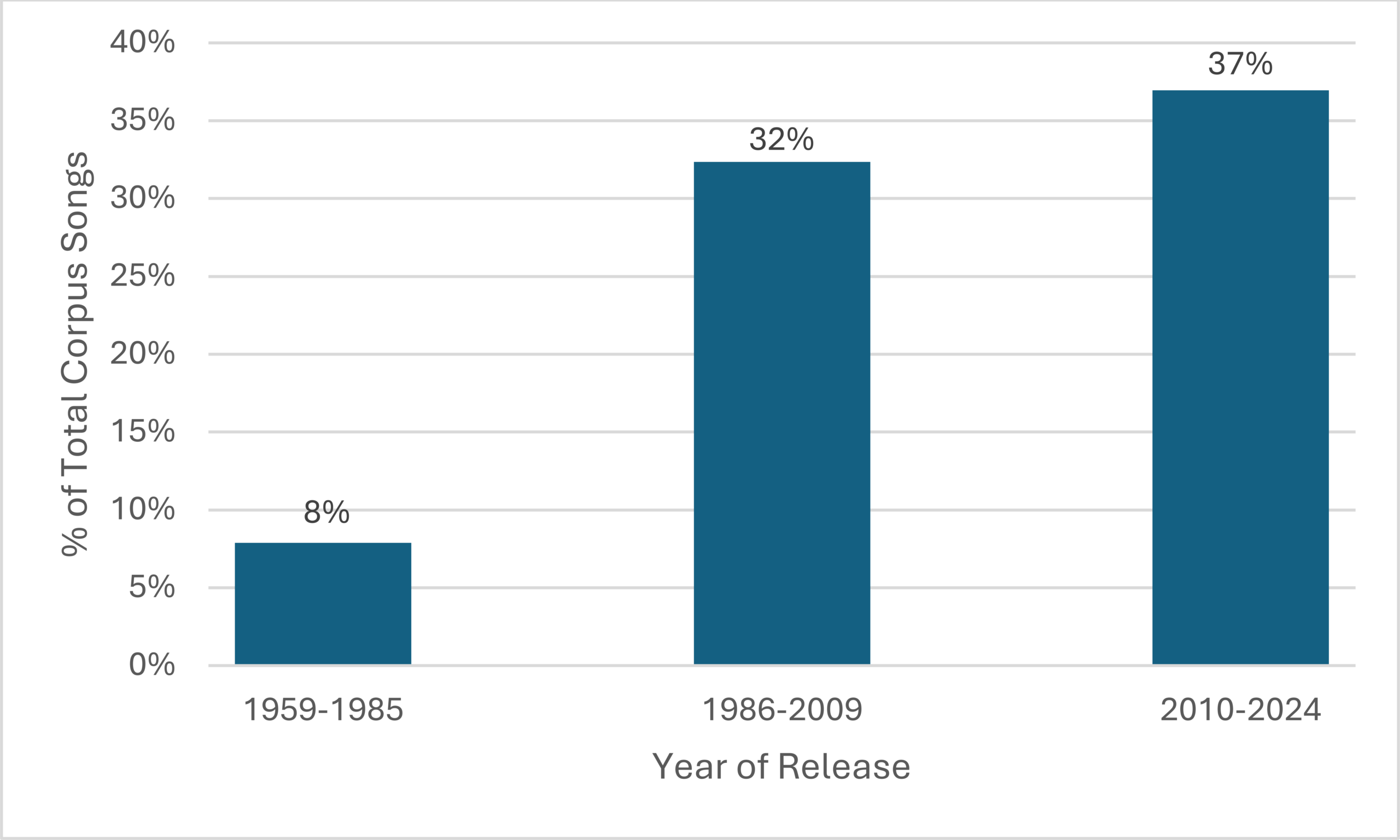

I analyzed 118 songs containing a rebuild,9 seen in Table 1 with the time the minimal state begins (“Time Min. State”), the source of the material used in the middle of the section (“RB Middle Material”), and the category of the secondary Billboard chart on which the song reached its highest peak.10 Rather than systematically drawing on such Billboard charts, a Rolling Stone top song list, or other “human-facing” collection of songs in which membership is determined by streaming counts or experts’ aesthetic evaluations, the collection analyzed in the study is a “music-facing” one, in which songs were included due to specific musical characteristics (Shea et al. 2024 4.1–4.2).11 Namely, in order to be selected for the study, a song needed to have a bridge-quality breakdown and rebuild with at least one distinct intervening stage in addition to the minimal state and the arrival.12 I assembled the collection of recordings by listening to the radio and to streaming services, communicating with scholars, students, and others who might know songs with this approach, reviewing Billboard charts, and doing online searches with language associated with descriptions of songs with rebuilds. Given that the discovery of songs with this approach in many cases was through casual listening, the collection of songs here analyzed to some extent undoubtedly reflects the music I tend to listen to, yet I made a concerted attempt to 1) ask scholars, students, and others with divergent tastes for examples of songs with rebuilds; 2) intentionally seek out songs which I either would never otherwise listen to or was not familiar with; 3) chose songs that would add to the collection’s racial, gender, and genre diversity. I sought songs that would provide chronological variety from 1959 to the present, with somewhat greater emphasis on songs of the last 15 years in order to provide greater detail on the most recent practices (Figure 2). The songs are largely in a style consistent with mainstream pop and rock,13 though a fair number of recordings that are outside the pop mainstream were included. 69 percent of the analyzed songs charted on the Billboard Hot 100, and slightly more than half of the 118 (51 percent) reached the top 10. 86 percent of the analyzed songs appeared on at least one Billboard singles chart, whether it be the Hot 100 or one of Billboard’s secondary charts like Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs or Adult Alternative Airplay. In order to give an idea of genre classification, I identified the secondary Billboard chart on which each song had its highest peak and arranged the various Billboard charts into categories (see Table 1 and footnote 10). Table 2 shows the Billboard genre categories and the number of analyzed songs in each category.14 Rebuilds that are longer and clearer were more likely to be included than shorter and less clear examples. Though many rebuilds have their roots in live performance practice, I did not include live recordings or other tracks with durations far beyond the scale of what could be released as a single (the longest recording among the 118 studied is The Who’s “Won’t Get Fooled Again” at 8:31 and the median song length is 3:53), as my focus was on the ways in which the breakdown and rebuild phenomenon could be encompassed within the relatively small confines of a studio recording that receives radio airplay.15

Table 1. The 118 analyzed songs ordered chronologically, along with the time of the start of the minimal state, the material used in the middle of the rebuild, and the category of the secondary Billboard chart on which it reached its highest peak. Table 2. A breakdown of the secondary Billboard charts on which each song reached its highest peak.

In this article, I primarily focus on close readings of individual examples of rebuilds, using them to illustrate common characteristics and issues raised by them. I use the 118-song collection 1) as a source for songs to analyze in greater depth; 2) to get an idea of the most common characteristics of rebuilds, developing a sense of the compositional “defaults” for them (cf. Hepokoski and Darcy, 9–10; Summach 2011, 4)16; and 3) to get some perspective on historical change in how rebuilds have been used and constructed. The calculated statistics can both give an idea of common approaches and enable more meaningful interpretations of individual songs, allowing for not just quantitative but also connective claims (White 2023, 30).17

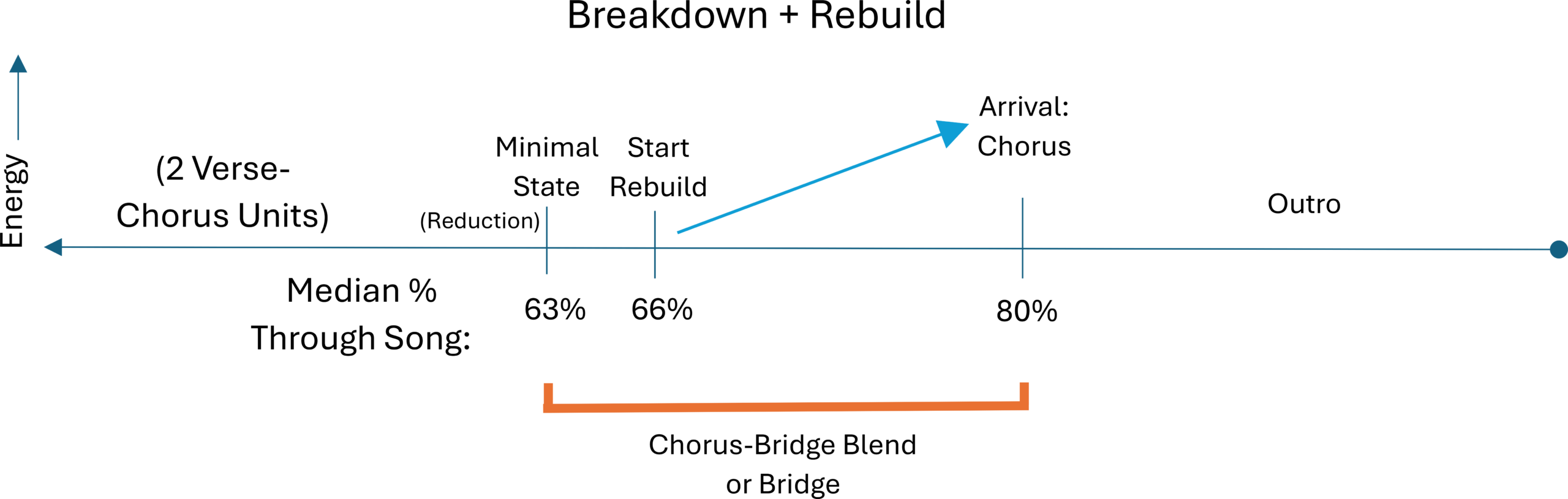

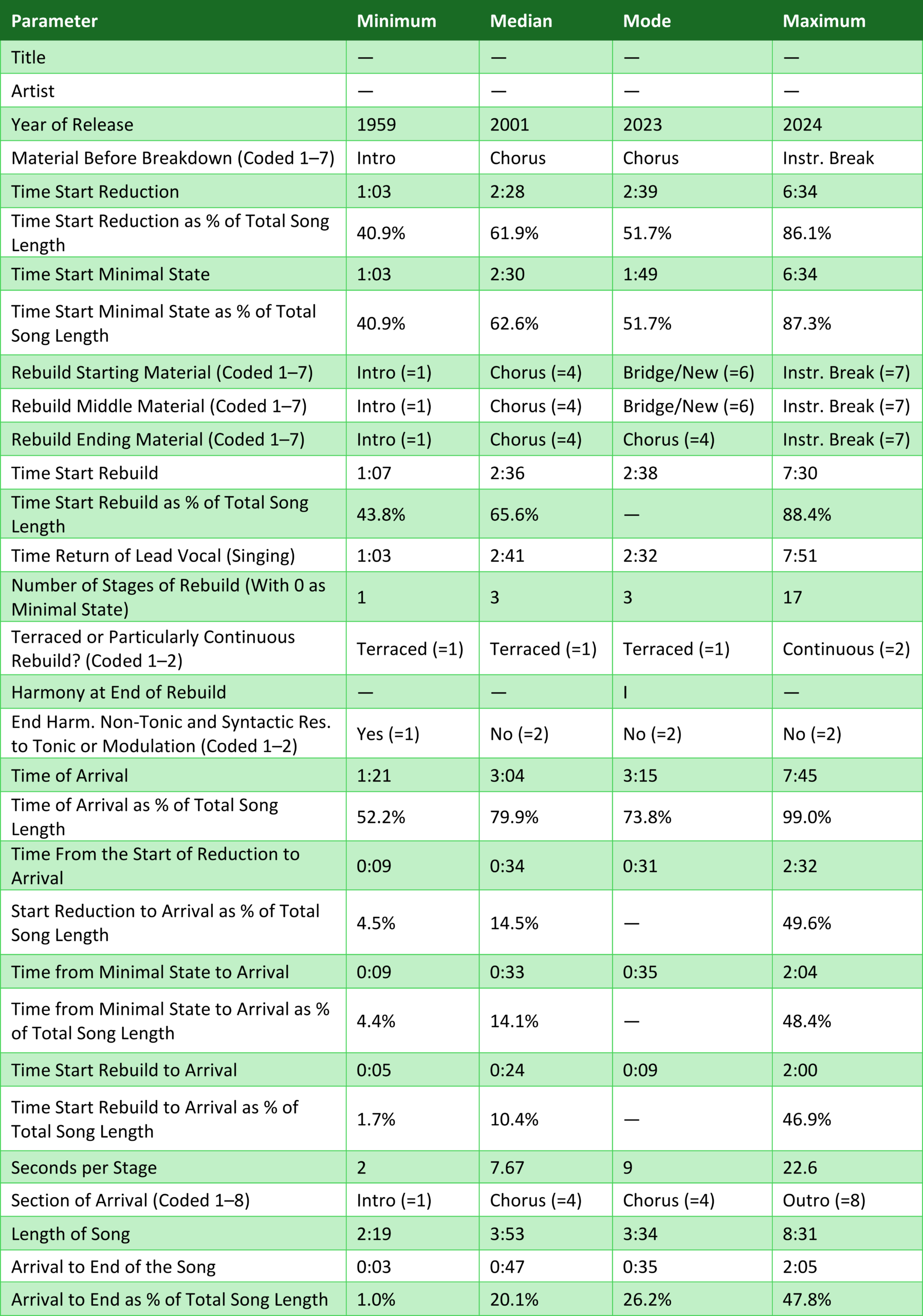

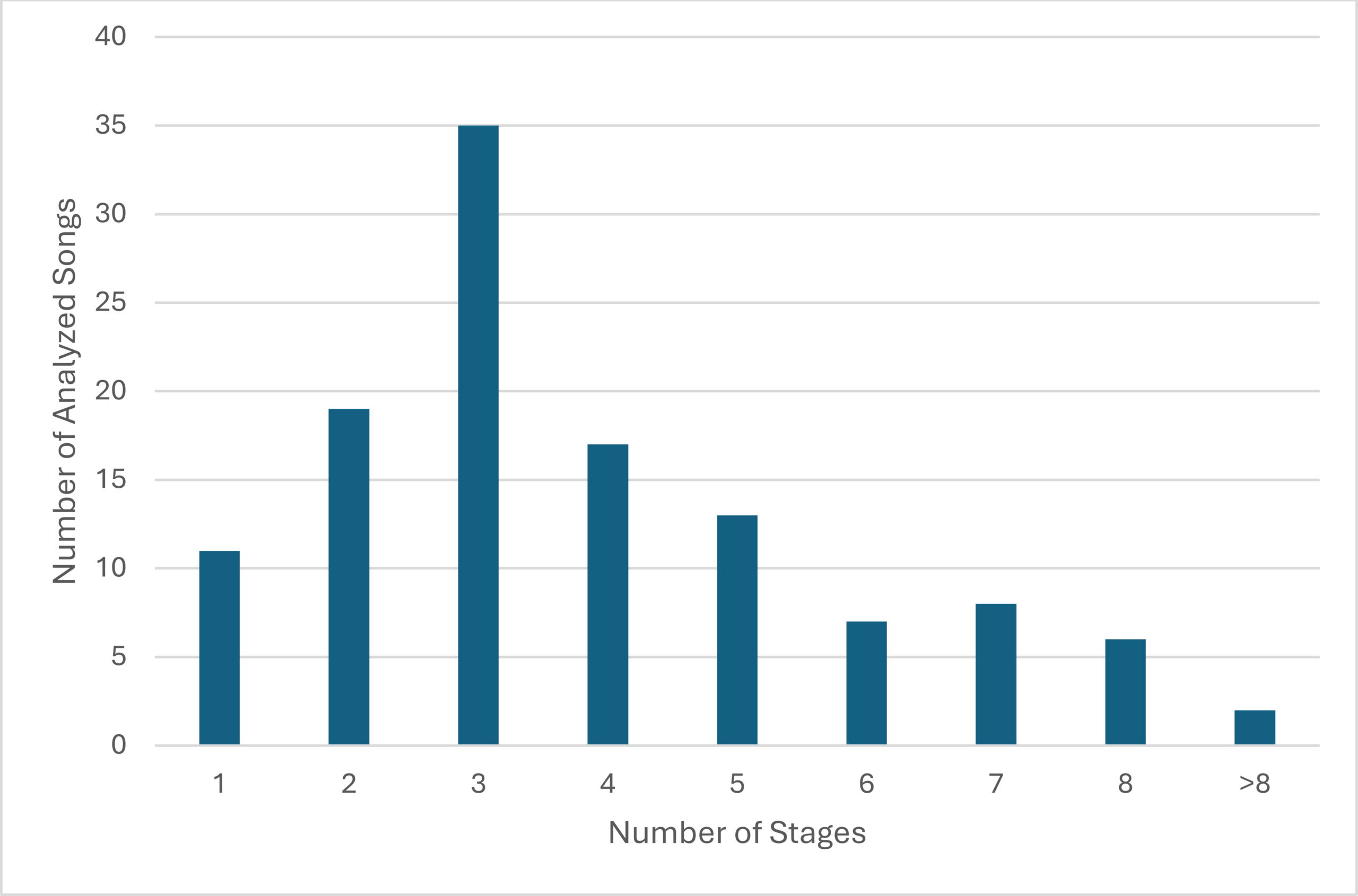

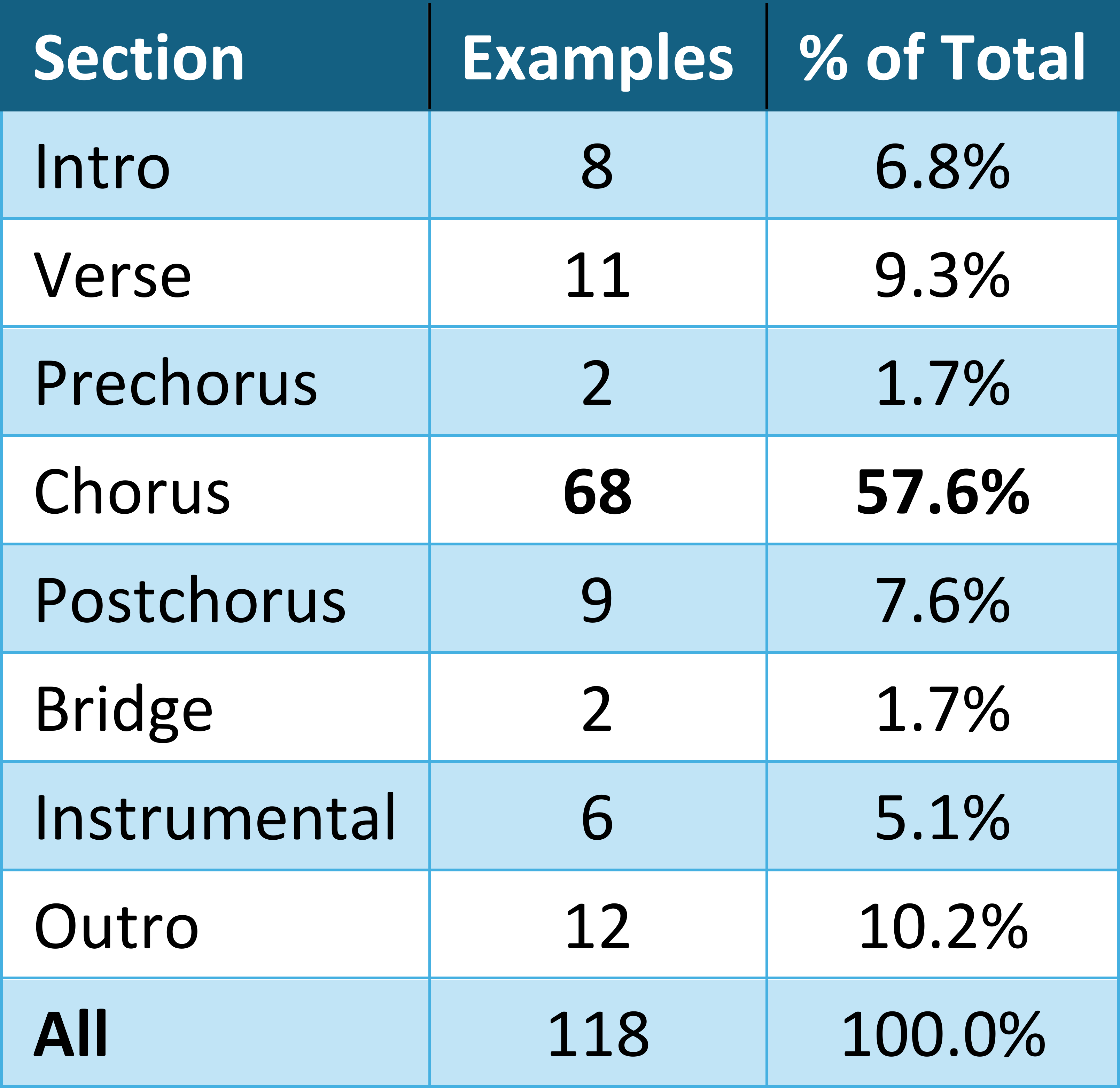

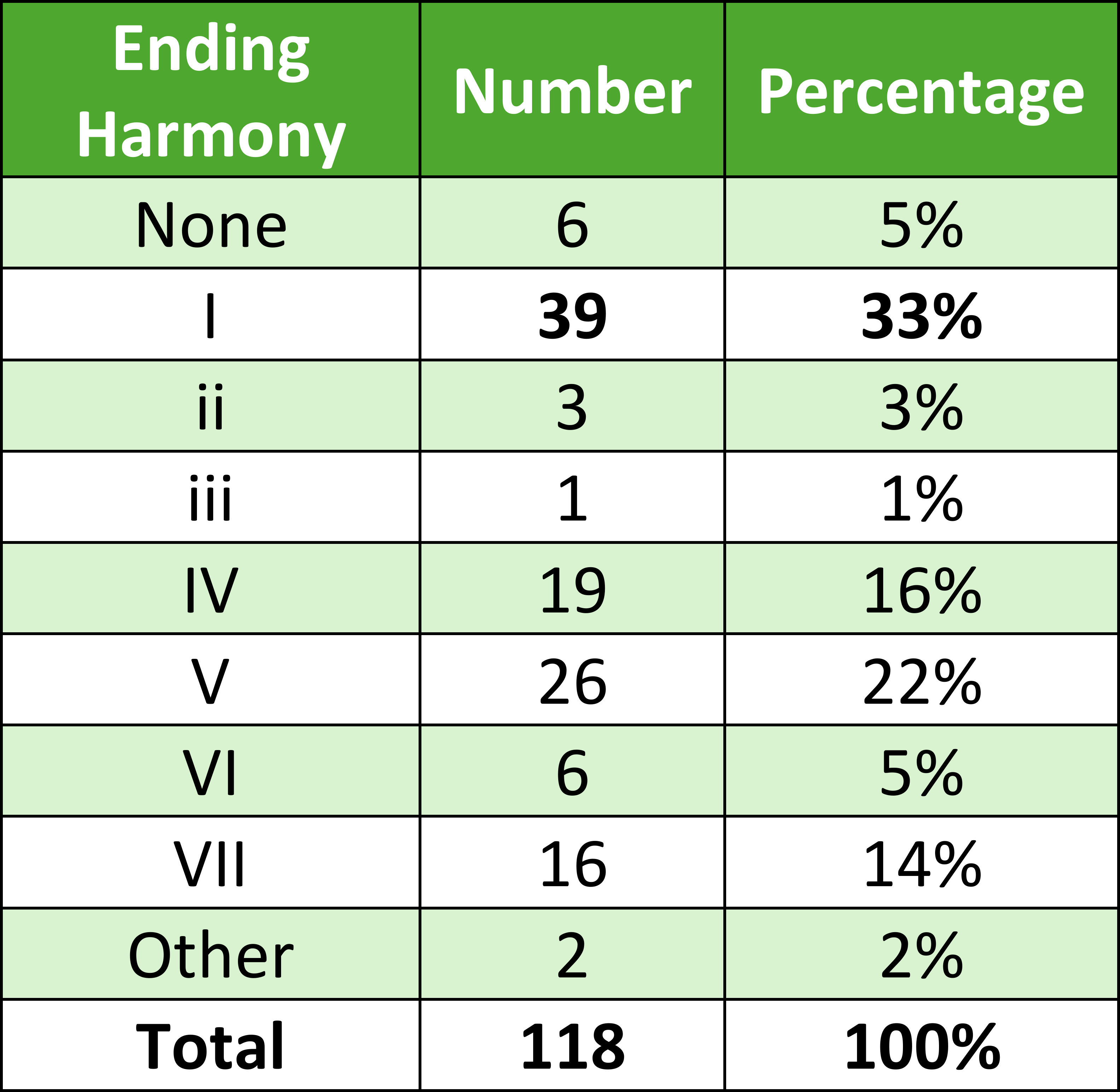

For each analyzed song, I answered 28 questions, which can be seen in Table 3 along with the range, median, and mode where meaningful. Because bridge quality can adhere to multiple different section roles successively (de Clercq 2017, 5.7), I identified the starting, middle, and ending rebuild material for each song. Appendix Table 1 contains the full data for all analyzed songs.18 As seen in Figure 3, the most common number of stages for the analyzed songs is three, which would indicate that a song breaks down to a minimal state, proceeds through three intervening stages, and then comes to an arrival. This most typically works out to four measures for each subdivision, combining to make for a 16-measure section, though I analyzed numerous songs with dimensions that differ from that standard. Consistent with Moore’s summary of bridge quality (2001, 223), Figure 4 shows that the minimal state at the start of rebuilds analyzed in this study occurs generally between 50% and 75% of the way through the song, with the median 62.6% and the mean 62.4%, both numbers very close to the 61.8% figure of the golden ratio. The median time from minimal state to the arrival is 33 seconds (Table 3). The median point through the recording that the arrival occurs is 79.9%, or about four-fifths of the way through the song. Table 4 shows the tendencies for the sections before and after given rebuild material. Table 5 shows that the most common section of arrival is the chorus.19

Table 3. The 28 parameters analyzed (in addition to title, artist, year, and Billboard chart data) for each of the 118 songs, with minimum, median, mode, and maximum.

In Sections 2 through 6 of this article, I explore aspects of rebuilds approximately in the order that they typically occur, using particular songs as examples. I first address breakdowns, their characteristics, and the liminal space they create. Second, I discuss the ways in which rebuilds can engage in dialogue with material previously used in the song, especially introductions, verses, and choruses. I then address primary and secondary building parameters as well as the insistent repetition of a newly heard line over a harmonic loop (the repeating-phrase rebuild). I then turn to the anacrustic cues and delays of satisfaction that often occur in the latter parts of rebuilds. Finally, I discuss what the analyzed songs as a group suggest about historical change in the use of this device, with an apparent decline in instrumental and verse-based rebuilds combining with a proliferation of repeating-phrase rebuilds.

2. Breakdowns as Liminal Spaces

Bridge-quality rebuilds are preceded by breakdowns. These are located approximately halfway to two-thirds of the way through a song and have a reduced texture compared with what has previously been heard. The dramatic change in texture, along with location in the middle of the song, contributes to the sense of bridge quality in the section (de Clercq 2012, 236). While rebuilds are often gradual, breakdowns are typically sudden.20 This is generally true in pop music of the last 60 years and is consistent with Mark Butler’s observations regarding EDM in his 2006 Unlocking the Groove (224) as well as Kofi Agawu’s model of “highpoints” in nineteenth-century art music, in which there is a gradual build to an apex but the decline is much more abrupt (1984, 162; cf. Huron 1992, 89).21 A sudden breakdown causes the music to enter a liminal, transitional state, in which conventional syntax can be twisted or abandoned and a formal loosening occurs. Such a loosening contrasts with the tight-knit sections that generally precede a breakdown, such as verses and choruses (cf. Caplin 1998, 17; 84–85).22 The liminal region of a breakdown-plus-rebuild can act as a transition from the core of a song into the closing portion, in which there are aural markers that the song is approaching its conclusion (see footnote 49 below). Just as with social rituals, common liminal attributes in popular song rebuilds include “the suspension of ordinary rules,” “an order turned upside-down,” and “a situation marked by volatility, ambivalence and potentiality” (Stenner et al. 2017, 143).

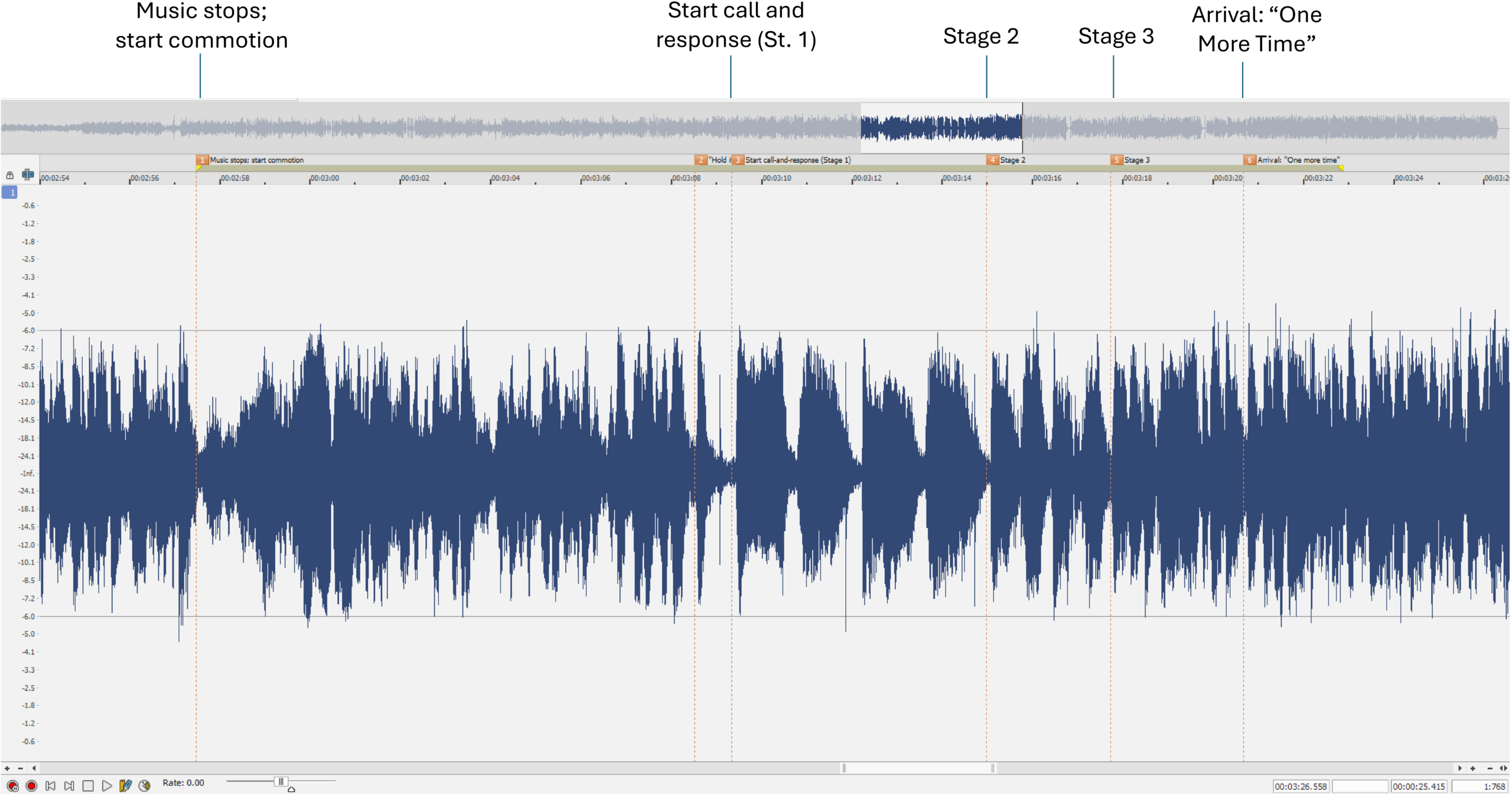

Ray Charles’s “What’d I Say,” the earliest song among the 118 examined and a gospel-influenced soul classic, provides an example of a breakdown prior to a rebuild and of some of the ways that these liminal characteristics can be manifested (Example 2). One of the most common occurrences in breakdowns is the removal of the drum kit and potentially other instruments. In “What’d I Say,” there is a complete stop of the music at 2:57. This break marks the minimal state, and a first-time listener might think the song has ended, a characteristic of many mid-song breakdowns (Summach 2012, 49–50). Instead we hear a cacophony of spoken voices, consistent with the tendency of breakdowns to move away from sung vocals, particularly sung lead vocals. The replacement of Charles’s singing with unintelligible speaking is a turning upside-down of the conventions of popular song and a temporary rejection of semantic meaning, with the previous musical order now disintegrated.23 Charles struggles to interrupt and to find the language to do so, his voice sounding but unable to articulate words. Finally he manages to take charge: “Wait a minute . . . hold it.” Often there can be ambiguity, as there is here, between whether an event is part of the breakdown or the start of the rebuild—sometimes events can be construed as both. Charles’s use of speech rather than singing represents a breakdown of the expected vocal approach, yet his attempt to bring order to the chaos simultaneously pushes in the direction of a rebuild.24

At 3:09 Charles follows with a sung “uhh” on the tonic E4 that begins an a capella call-and-response with the backing Raelettes, who at this point make their first appearance in the recording. This is a return of conventional singing, yet words are still not used—there is incoherent, sub-linguistic moaning (the eroticism possible in the liminal space of the rebuild) rather than the conventional syntax of language. Both Charles’s previous speaking and the singing on vocables sound improvisatory, another common characteristic in the breakdowns of rebuild songs. There is a sense in many breakdowns and rebuilds of being outside the scripted portions of a recording, in a region where potentially anything can happen and the singer has freedom to ad lib.25 The improvisatory approach also connects with the traditions of live gospel singing, soul performance, or EDM sets, in which there can be improvisatory interaction between the performer and a congregation or audience or between a DJ and club dancers.26 In “What’d I Say,” the rhythm of the call-and-response rapidly accelerates until Charles’s scream on a retransitional dominant B4 at 3:20 brings the arrival, which is marked by the return of both the band and conventional language (“One more time”).

3. Adapting Previous Material

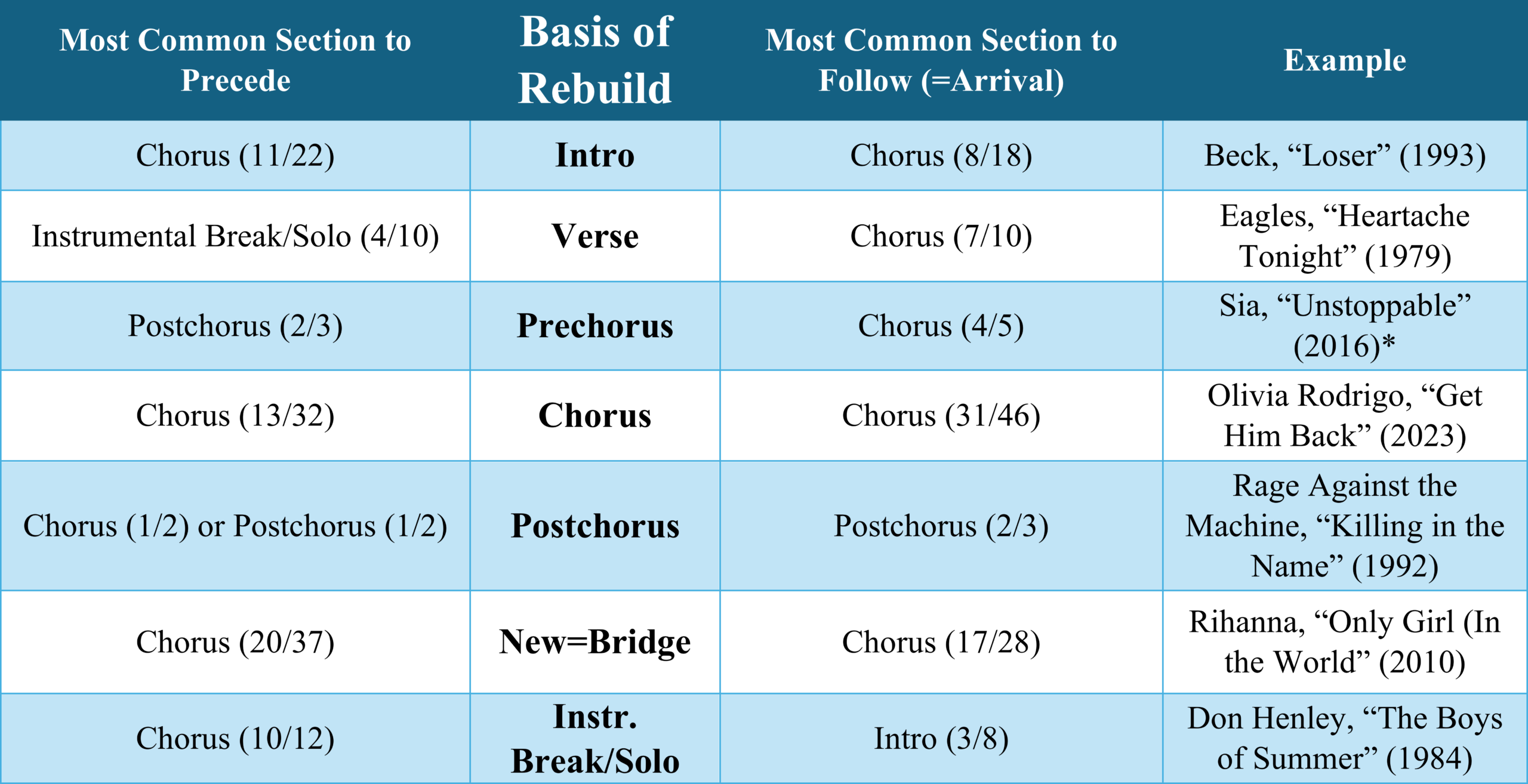

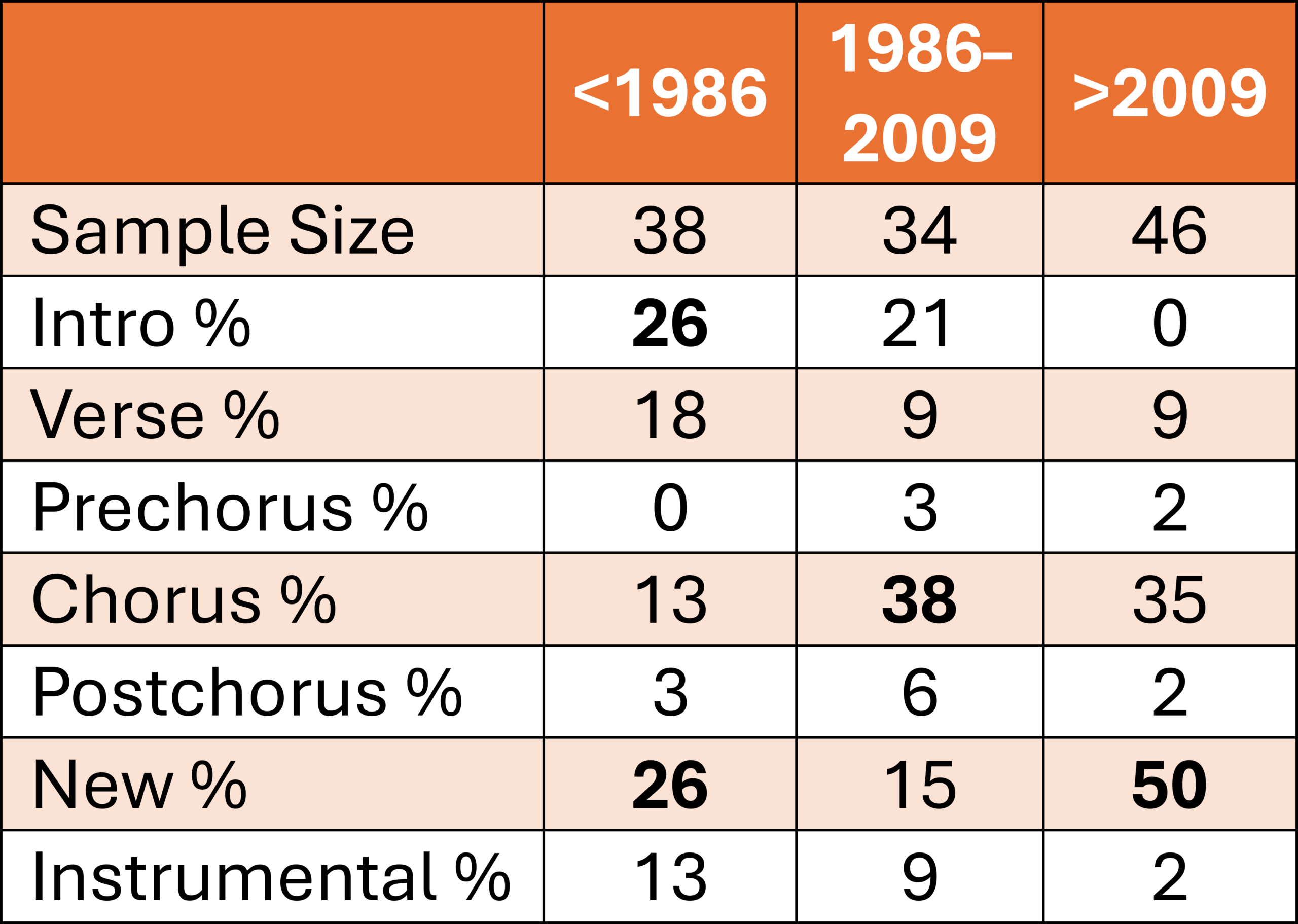

Once the bridge-quality breakdown has occurred, a rebuild can start, either with new material or by reimagining material previously used in the song. If new vocal material is used, as in Rihanna’s “Only Girl (In the World)” (2010), then the rebuild constitutes a more or less pure bridge. Similarly, an instrumental rebuild can use new material and thus constitute an instrumental break, as in Blue Öyster Cult’s “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” (1976). But when material previously heard in the song, such as the intro, verse, or chorus, is used as the material for the rebuild, either in a straightforward manner or through significant transformation, there is a blend between bridge quality and another section role (de Clercq 2012, 236).27 As seen in Table 6, most of the analyzed songs (60 percent; all but “New” and “Instrumental”) use previous material from the song in the rebuild, creating most commonly intro-bridge, verse-bridge, or chorus-bridge blends.28 This is a major difference from a prechorus, which almost always uses material different from the verse that has preceded it; a rebuild occurs in a position in a song where there are several possible sources for material that can contribute to a blend—intro, verse, prechorus, chorus, or postchorus. In the remainder of this section, I discuss examples of uses of the three most common sources of previous material repurposed for a rebuild, noting some differences in how each type of material is typically used: 1) intro (used in 14 percent of analyzed rebuilds), 2) verse (12 percent), and 3) chorus (29 percent). In each case the previous material maintains its identity yet is transformed.

One option for reusing previous material is to employ a song’s intro, creating an intro/bridge blend. The rebuild in Beck’s “Loser” (Example 3) is a version of the song’s intro, using that material in a bridge position in the song and creating textural contrast with the rest of the recording. Examination of this section shows how a bridge-quality rebuild can replicate elements of a buildup introduction (Attas 2015) yet differ from it in important ways. The fact that a buildup introduction builds just to the baseline texture of the song, while a rebuild usually ascends to the recording’s climactic point, will often result in some differences of approach: rebuilds like that in “Loser” are more likely to exploit the parameters of timbre (especially filters), dynamics, register, and rhythmic density (see Section 4 below).

Example 3. Comparing the introduction and the rebuild in Beck’s “Loser.” Audio 3a: intro; 3b: rebuild.

Intros in general have an anacrustic quality, as they create anticipation for the initial entry of the lead vocal and the start of the core of the song. In the buildup intro in “Loser” there are three stages, starting with a slide guitar riff for two measures, then adding the drum kit (a sample of Johnny Jenkins’s 1970 “I Walk on Guilded Splinters”), then two measures later adding a bass, with this fuller texture continuing for four measures to total eight for the introduction. The return of the intro in the middle of the song at 2:25 brings its anacrustic character to the breakdown, combined with new bridge quality. Beck’s spoken “Drive-by body pierce” belongs hypermetrically to the previous chorus but also launches the breakdown. The rebuild expands the scale of the buildup introduction, totaling 12 measures that divide into an 8+4 arrangement. In addition to expanding the intro, it also rearranges the sequence of instrument entries and thereby scrambles the previously established musical order. While in the intro the slide guitar sounded first, in the breakdown and rebuild the first instrument to appear is the drum kit. After a D3 (tonic) backing vocal drone is added at 2:32, the slide guitar riff returns. The previous regime of the song is further upended by a backwards version of the chorus, with a recording of Beck’s vocals reversed. In the last four measures of the rebuild a full instrumental texture returns, with the sitar and bass resuming the main riff heard throughout the song. This feels like a recapitulation and an intermediate landing point, but a full sense of arrival does not come until the lead vocal returns four measures later at 3:00, restarting the (now forwards) chorus.

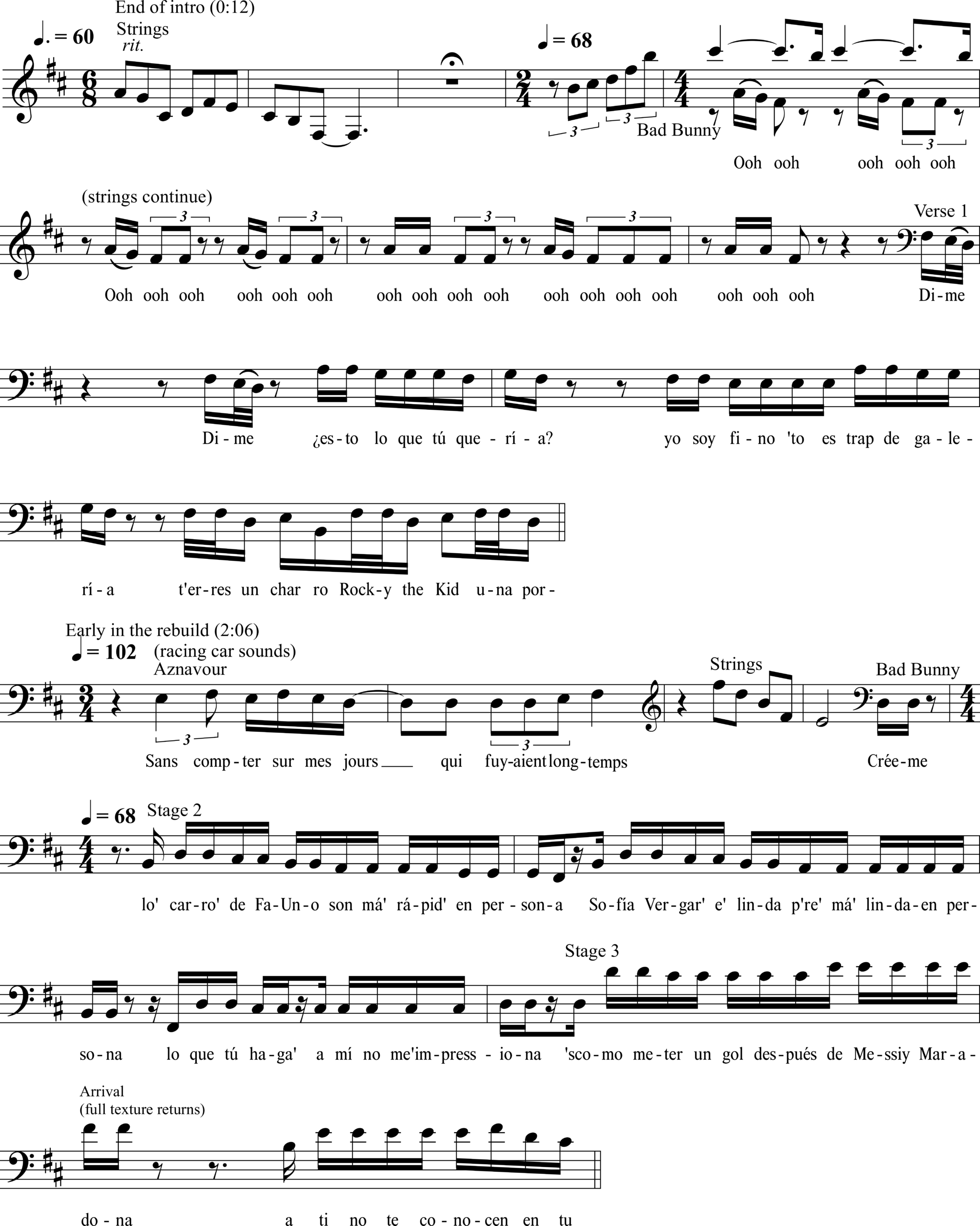

Another possibility for using previous material from the song as a rebuild partner is to employ verse melody and harmony. This approach is one that is associated much more with earlier decades than with the twenty-first century (see Section 7 below), and more recent songs that use it tend to be nostalgic in other respects as well. Songs that use verse material for a rebuild most commonly are preceded by an instrumental break or solo, as in the Rolling Stones’ “Midnight Rambler” (1969) and R.E.M.’s “Man on the Moon” (1992), or by a return of the introduction, as in Boston’s “More than a Feeling” (1976) or Bad Bunny’s “Monaco” (2023; Example 4). In “Monaco” a recapitulation of the introduction, acting as a breakdown, is followed by ambiguously verse-like material as the basis for a rebuild. Combining intro with succeeding verse material is a natural progression for a breakdown and rebuild, as the teleological and anacrustic character of that previous sequence returns to build towards a more dramatic arrival. The breakdown that occurs after the first chorus in “Monaco” at 1:57 brings back the strings, harp, and celesta from that opening, though with the new addition of racing car sounds and a sampled vocal singing in French (the sample comes from Charles Aznavour’s 1964 “Hier encore”). The triple meter of this breakdown differs from the compound meter of the intro, though both are alternatives to the typical quadruple meter of the verse and chorus. This breakdown connects with the song’s opening but creates bridge quality by virtue of its position in the song and by the contrast with Bad Bunny’s prior melodic rapping in the first verse-chorus unit—the language is switched from Spanish to French, there is a totally different singer, and the meter is changed.

Transitioning away from the Aznavour sample and the triple meter, Bad Bunny at 2:12 implores “Créeme” (“Believe me”), a call for attention that echoes the “Dime” (“Tell me”) at the start of the first verse. A verse from early in the song will usually have a reduced texture in comparison with the chorus that succeeds it, so there needs to be an even more reduced texture in a verse/bridge blend to create a sense of bridge quality. Here, the Bm-Em shuttle from earlier in the song returns, but the texture is greatly reduced, with the percussive bass behind a filter and no other instruments. Bad Bunny then, while not precisely repeating the melodic line of the verse (creating ambiguity as to whether he is truly returning to it), brings back the more chant-like singing approach of that verse as well as his lower register in a manner that contrasts with the more melodic approach and higher register of the chorus. The melody here can be heard as a version of the first verse melody, with both moving gradually downwards stepwise through a B natural-minor scale with repeated sixteenth notes. Additionally, while the chorus had pairs of rhymed lines, Bad Bunny here returns to the verse approach of grouping four lines with the same rhyme: persona–persona–impresiona–Maradona. As the rebuild proceeds, he leaps up an octave in register, the most dramatic gesture in the entire song, leading to the arrival on a new melodic highpoint of F#4 at 2:27. At this moment, the filter on the bass is removed and the full virtual drum kit returns. The combination of the 3/4 sampled material with orchestra followed by this rebuild forms a larger bridge-quality grouping (cf. the “broader ‘B’ group” referenced by de Clercq 2012, 224). The blend with prior material is more ambiguous in this case than with “Loser,” but enough similarities with the intro and first verse are present as to allow listeners to make the connection.

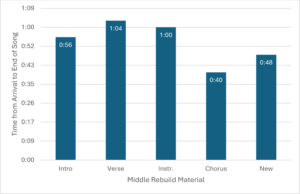

As with using an intro from the start of the song as a rebuild partner, when verse material is used there is often a sense of restarting the song, creating a revised version of the beginning of the recording. As a result, there is typically more time from the arrival to the end of the song if an intro, verse, or instrumental is the basis of the rebuild (Figure 5). Comparing the mean time for this group (the first three bars on the left) of one minute with that for prechorus, chorus, postchorus, and new/bridge as a group (49 seconds), p = .02 for a two-sample t-test.29 This reflects the extra duration needed to move through an additional verse-chorus cycle and get to the outro when an intro or verse is used as the basis for the rebuild; with an instrumental rebuild, time is needed to reestablish the vocal and the lyrical narrative. This is particularly the case in “Monaco,” where the time from the arrival to the end of the song is two minutes, greater than that in any other analyzed song except for Don Henley’s “Boys of Summer,” also a nostalgic throwback. The fact that the breakdown and rebuild in “Monaco” occur after the first chorus rather than the second contributes to these unusual proportions.

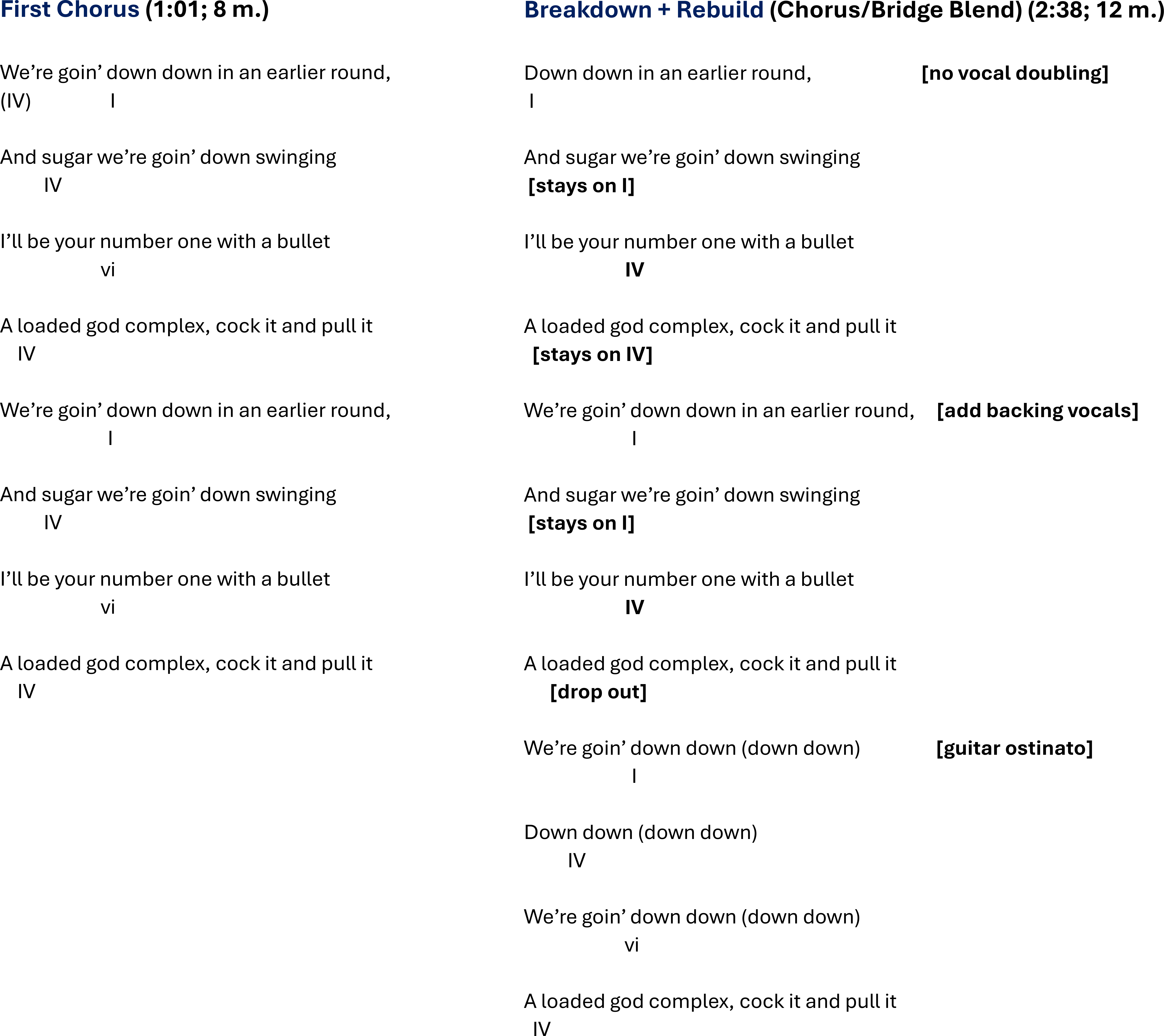

A third source for rebuild material—the most common—is the chorus. While there is a good deal of variety among the possible combinations of material used before, during, and after a rebuild, with 59 unique combinations in the 118 analyzed songs, Table 7 shows that three of the six most common three-part sequences use chorus material for the rebuild. In Fall Out Boy’s “Sugar, We’re Going Down” (Example 5), previous chorus material is employed to rebuild from a breakdown and is transformed in the process. The first chorus, starting at 1:01, features a doubled lead vocal and one chord change per measure, as well as backing vocal “ahhs.” This initial chorus is eight measures long and divided into two four-measure groups, the second of which is a repetition of the first. After another verse and the second iteration of the chorus, there is a breakdown and rebuild starting at 2:38 that uses the chorus material but alters it significantly to create bridge quality.

When chorus material is used for a breakdown and rebuild, the transformation for the breakdown tends to be particularly stark because choruses are usually energetic highpoints as well as relatively stable points of arrival. A chorus therefore needs significant alteration in order to act as a low-energy breakdown and take on a transitional role.30 With a previously-used core section becoming the basis of a transitional rebuild, material that originally was tight-knit becomes formally loose (Caplin 1998, 17; 84–85).31 The assumption of a transitional character can be accomplished through a dramatic reduction in texture, but in some cases there are additional alterations. The breakdown and rebuild in “Sugar, We’re Goin’ Down” use 12 measures and can be divided into three four-measure hypermetric units. Returning from previous choruses in “Sugar, We’re Goin’ Down” are the melody, the lyrics, and, to an extent, the harmonies. But the previously high-energy chorus is broken down here by stripping away vocal doubling from the lead singer Patrick Stump, by a significant reduction in the instrumental texture, and through the slowing of the harmonic rhythm. Rather than I-IV-vi-IV with one chord per measure, the harmonic progression is simplified to I-IV, with each chord now lasting two measures. In the second four-measure group of the 12-measure section, starting at 2:49, energy is built by greatly increased backing vocal activity. A dropout in the final measure of this four-bar hypermeasure creates expectation that the arrival is imminent, but additional rebuilding yet remains. With a chorus as the basis of a rebuild, the end of the rebuild can be a natural fit because choruses are already a high-energy event. But to push past the energy levels of previous choruses and distinguish the end of the rebuild as a decisively climactic moment, there need to be new elements not present in previous choruses. In the final four measures of the “Sugar, We’re Goin’ Down” rebuild, the electric guitar, drums, and bass are much more active yet use patterns different from those heard in previous choruses, even as the previous faster harmonic rhythm returns. The increased activity represents a new highpoint and at last leads at 3:14 to the return of the fully textured chorus, now with a double-time feel and incorporating vocal and instrumental elements previously heard in the rebuild.

The use of chorus material for a rebuild followed by an arrival chorus particularly signals that a song is approaching its conclusion, since immediate repetition of a chorus is a sign of nearing the end of a song (Summach 2012, 125). This is consistent with Figure 5 above, showing that analyzed rebuilds using chorus material had the shortest median time from the arrival to the end of the song. Some rebuilds use different (often new) material, but then use chorus material just at the end of the build—these usually constitute “breakdown choruses” (Byron and O’Regan 2022, 315), which I will discuss below in Section 6.

4. Building Energy

Just as with a prechorus (see Summach 2011, 3; Nobile 2022, 1.4 and 3.2–3.3), energy can accumulate in rebuilds through a number of specific musical parameters. Leonard Meyer classified parameters as “primary” or “secondary” (1980, 189–190; see also Meyer 1989, 14–16), and rebuilds move to an arrival through a combination of these. Primary parameters include melody, rhythm, and harmony, while secondary parameters include timbre, texture, register, and dynamics. Both primary and secondary parameters contribute to a sense of potentiality in this liminal region (Stenner et al. 2017, 143), creating expectation of achieving a highpoint. Primary parameters allow building to a syntactic climax, while secondary parameters build to a statistical climax.32 Syntactic climaxes depend on a particular style’s logic and can include the recapitulation of previous material and the resolution of harmonic tension. Statistical climaxes, on the other hand, feature the highpoint of dynamics and/or register and are less dependent on the grammar of a particular style (Meyer 1980, 189–190).33

A rebuild can arrive at a syntactic climax by returning to previous material and bringing back tonic after harmonic or tonal contrast, as in “I Will Follow” by U2 (1980). In this song, a switch of mode from major to the parallel minor at the start of the breakdown at 2:06 and the subsequent addition of a new melody (“Your eyes make a circle . . .”) create contrast with what has previously been heard. At the end of the rebuild, at 2:44, there is a return of the intro guitar riff and major mode. This is a form of syntactic climax that connects with how a Tin Pan Alley or “classic” bridge transitions back to A material (de Clercq 2012, 76). And at the conclusion of some rebuilds there is a standing on the dominant not unlike that in sonata-form retransitions—as in, for example, the Rolling Stones’ “Let’s Spend the Night Together” and Amy Winehouse’s “Back to Black.” Table 8 shows how most of the bridge-quality rebuilds analyzed for this study are “continuous,” ending off tonic, with only one-third ending on tonic (“sectional”; Endrinal 2011, 29). Thus, harmonic or tonal contrast can play a crucial role in creating tension during a rebuild, and its resolution can add to a sense of arrival, particularly in older songs. But the more common practice of popular music in the last 30 years of using a loop throughout a song, with most pop hits since 2010 employing only one chord progression (Peres 2016, 65; Spicer 2017, 21 & n. 22), is at odds with standing on the dominant or another chord at the end of a rebuild or bridge.

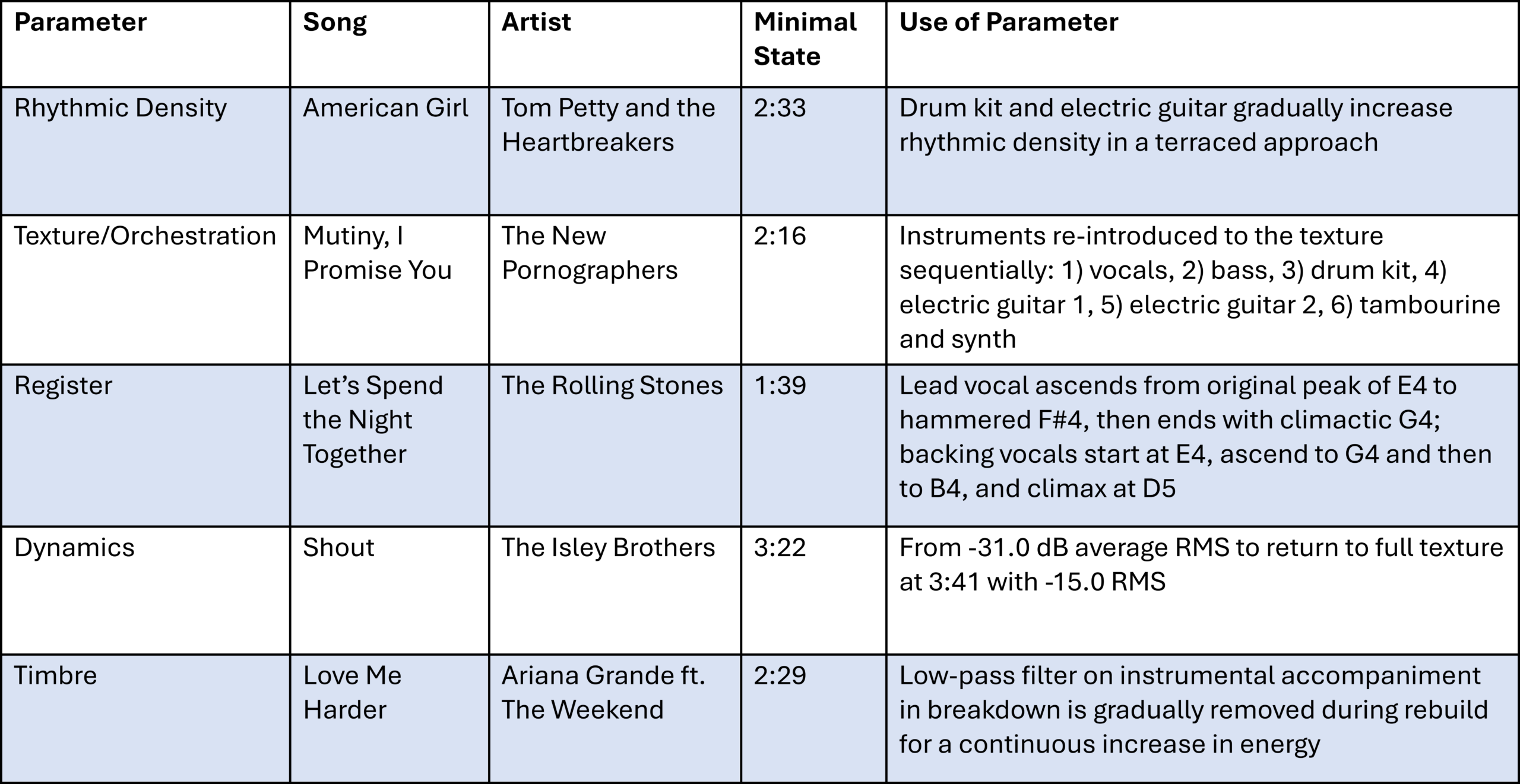

The Isley Brothers’ “Shout” (1959; Example 6) employs a shuttle between F major and D minor throughout most of its duration, including during the breakdown, rebuild, and arrival, and in this respect anticipates many twenty-first century examples. Harmonic contrast or tension plays no role in the delineation of the rebuild structure and arrival in the song; the sense of building is instead conveyed through changes in energy (Temperley 2018, 141–142). Five of the most important parameters that can build energy in a rebuild are 1) rhythmic density; 2) texture/orchestration; 3) register; 4) dynamics; and 5) timbre (Table 9).34 Rebuilds usually make use of a combination of these parameters in order to teleologically advance towards the arrival, and each can build in either a terraced or continuous manner. “Shout” relies on these “secondary” parameters to build to a highpoint and serves as an example for how each can be employed.

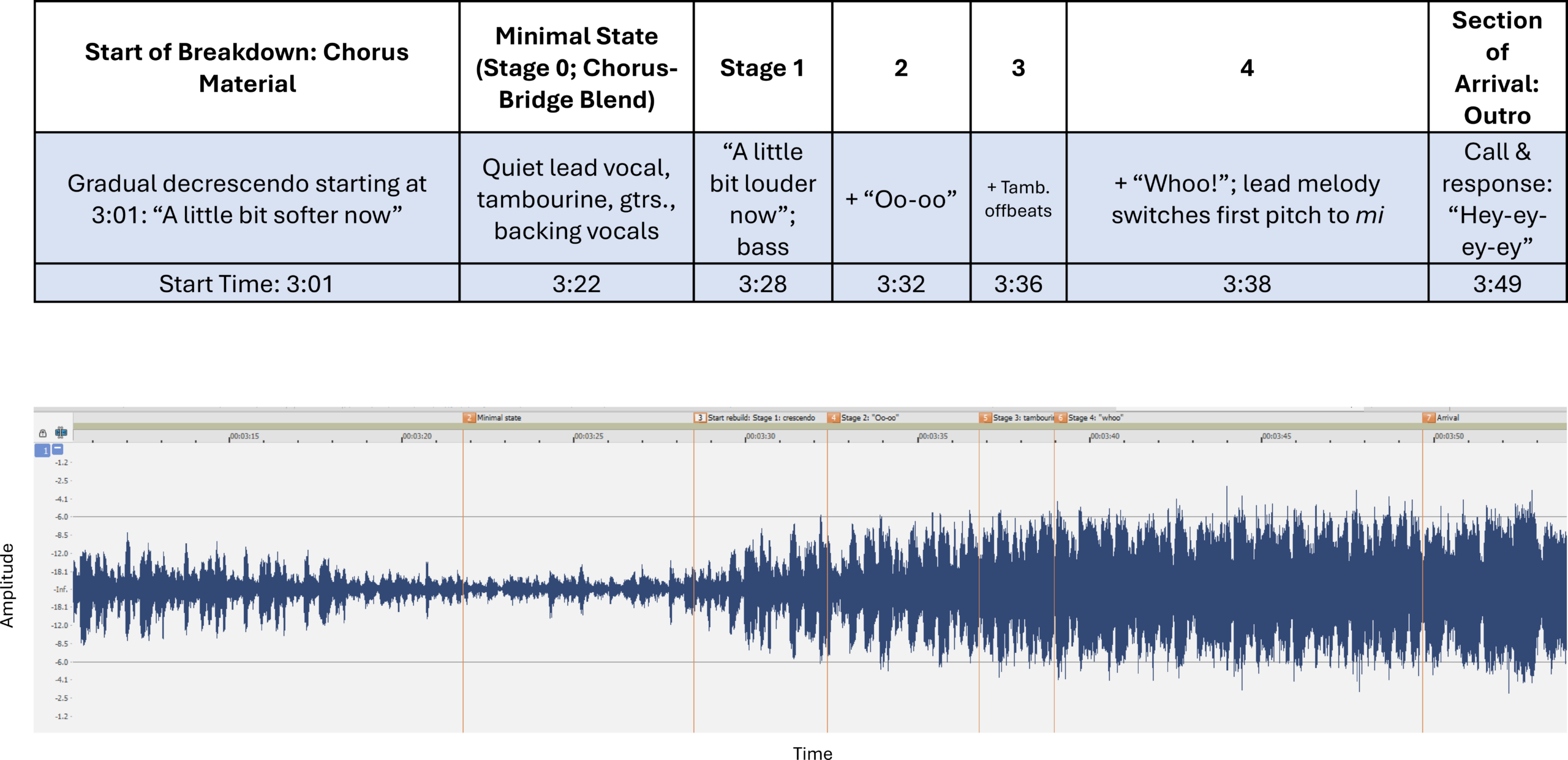

Like “What’d I Say,” “Shout” is a gospel-influenced classic spread over two sides of a 45, providing a longer, more “live” experience than was possible with only one side of a single. The stoppage at 2:15, allowing flipping over of the record, is part of a centrally located rhythmically-free breakdown. At the conclusion of this breakdown, at 2:45, the music returns to the full manic texture of its chorus, only to then commence a second, much more gradual breakdown in which the lead vocalist Ronald Isley describes the process (“a little bit softer now”). As this breakdown occurs, there is a reduction in rhythmic density, with a switch to a half-time feel and the tambourine giving up its backbeat pattern in favor of playing only on the downbeats at this slower tempo.35 In the rebuild, beginning at 3:28, this change is reversed, with a dramatic switch back to the fast-tempo normal-time feel and the return of the backbeat pattern at 3:36. Increased rhythmic density is also created in the rebuild by the addition of backing vocal “ays” and high “woos” every two measures. Though the texture is built to an extent during the rebuild by the addition of the backing vocal elements, “Shout” differs from most twenty-first century examples of rebuilds in that it does not rely as much on changes in texture to create a sense of breaking down and rebuilding. The texture at the quietest point of the breakdown in fact includes all the instruments that were previously present in the full texture and that will be heard at the arrival: electric guitar, tambourine, percussive tap, backing vocals, lead vocal, and bass. This rebuild relies more on register to increase energy, with the lead vocalist topping out at F4 during the breakdown, then raising up to regularly hit A4 once the rebuild progresses. The high backing falsetto “woos” also are a higher-register element that are added during the section.

Dynamics are the clearest differentiators between breakdown, rebuild, and arrival in “Shout,” and the recording features a very continuous (rather than terraced) approach to these, allowing for a gradual build. As seen in Example 6, at 3:28 Isley switches his lyric from “a little bit softer now” to “a little bit louder now” to mark the start of the dynamic rebuild. The clear dynamic pattern in the rebuild of “Shout” contrasts with the waveform in a more recent example of a rebuild, Lizzo’s “About Damn Time” (2022; Example 7), where there is less density in the waveform during the rebuild than in the rest of the song, but the local peaks (drum hits) continue to be very near a clipping level through use of digital limiting. Timbre is a fifth secondary parameter that can be used to rebuild. In the case of “Shout,” the timbral differences occur primarily in the vocals, with Isley using a hushed near-whisper during the breakdown but during the rebuild switching to an anguished, straining timbre that fits with the louder dynamic.36

Additional parameters beyond these most common five, such as tempo and phrase rhythm, can add to a rebuild. Huron notes how performers building to a climactic point tend to accelerate (2006, 326). There is a general association in popular music between building texture and accelerating tempo in songs recorded without a click track or sequencing (see, e.g., Baur 2020, 37–38; Attas 2015, 278). The Righteous Brothers’ “You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feelin” (1964) has a rebuild with both an increasing tempo as well as accelerating phrase rhythm. Example 8, a tempo map generated in Melodyne, shows a pattern of gradual acceleration over the course of the rebuild from 92 BPM at 1:48 to 99 BPM at 2:52 (with the “bring it on back” rapid call and response at the very end of the section). This is another example of continuous, rather than terraced, rebuilding. With the exception of the slight acceleration and drop back down at 1:51–1:58 (with the lead singer’s first phrase “Baby, baby, I get down on my knees for you” pushing and pulling the pulse expressively in this initial phase), this larger overall acceleration takes place very gradually over the course of the minute-long section, boosting energy in a continuous manner. The tempo acceleration is relatively subtle in itself, yet it reinforces changes in other parameters.

The gradual acceleration of tempo is also accompanied by an acceleration of vocal phrase rhythm, of rhythmic density, and of alternation of the two different vocalists. The acceleration of phrase rhythm here is terraced (or “discrete,” to use the term employed by Jeremy Smith in his discussion of continuous changes in EDM (2021, 1.2)), rather than continuous. The “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’” rebuild (Example 9) is characterized largely by a call and response between the two vocalists, Bill Medley and Bobby Hatfield. This accelerating antiphony recalls that in “What’d I Say” and represents an approach used in many rebuilds. Initially (“Baby, baby…”), there is significant temporal distance between the two singers. They alternate calm, lyrical four-measure phrases with a 2+2 phrase rhythm, in each case following two measures of singing with two measures of vocal rest (Stephenson 2002, 7). These eight measures are followed by two more four-measure phrases using a 2+2 approach, this time with Medley and Hatfield homorhythmically singing in harmony. At the end of this second group of eight measures (2:36), there is a marked acceleration of vocal phrase rhythm, similar to that discussed by Lee (2020, 1.2, 2.4) and Summach (2012, 29–30) in other contexts. The call-and-response between Medley and Hatfield now occurs in a much smaller time span, with the two alternating “baby” and then “I need your love” within a single measure, their contributions even overlapping. This more rapid alternation occupies the final eight measures of the rebuild, the vocals now taking on a strained and improvisatory character. Finally, at 2:55, the chorus is reachieved, with Medley and Hatfield once again in their previous arrangement of a lead and a homorhythmic harmony backing vocal.

Although they have discrete stages, bridge-quality rebuilds tend to have a more continuous and gradual retransitional approach to building energy than buildup introductions and traditional pop song bridges, the latter of which present contrasting material and then usually retransition back to the A material relatively abruptly. Continuous, non-discrete change is associated with instability, tension, and discomfort (Smith 2021, 3.1) and thus is particularly well-suited for liminal passages like breakdowns and rebuilds. Secondary parameters like dynamics and register tend to be more susceptible to continuous change, while primary parameters like harmony and melody tend to be changed more discretely. Of the five main parameters used for rebuilding, rhythmic density and texture/orchestration tend to be terraced,37 while dynamics and timbre have greater potential to be treated continuously. The use of a gradually opening filter, like the one employed in the rebuild of Ariana Grande and the Weeknd’s “Love Me Harder” (Example 10), allows for extremely continuous change. Register has the potential to be treated continuously (as it is in the rebuilds of Bruno Mars’s “Locked Out of Heaven” (2012) and the Black Pumas’ “More Than a Love Song” (2023)), but often is terraced, with some rebuild vocals switching to a higher octave after four or eight measures. Outside of the five main rebuild parameters, tempo is another parameter that is sometimes increased in a continuous manner, as it is subtly in “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’.” Of the 118 songs analyzed, 26 (22 percent) have a particularly continuous approach to rebuilding, resulting in a more gradual accretion than in the songs that build in a more clearly terraced fashion. Rebuilds that incorporate a more continuous approach still have identifiable stages, but manifest significant continuous change within one or more of them.

5. The Repeating-Phrase Rebuild

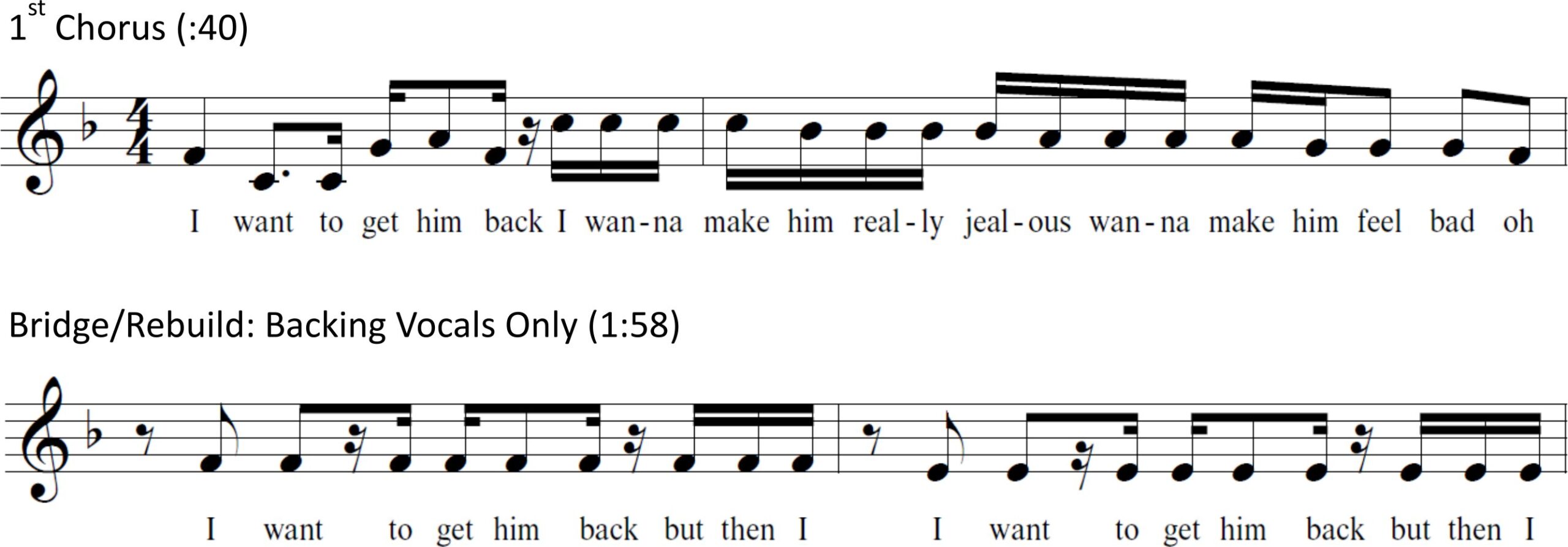

In addition to building through specific parameters, rebuilds can also escalate tension through insistent repetition, typically musematic (Middleton 1983, 238). In Olivia Rodrigo’s “Get Him Back!” (2023; Example 11), the previous chorus line “I want to get him back” is repurposed and transformed in the rebuild. Such repetition of a single melodic line, usually over a harmonic loop or pedal, I refer to as a repeating-phrase rebuild. Stasis in the form of a repeating melodic phrase over a loop allows for dynamism in the building of texture, instrumentation, dynamics, rhythmic density, and register. The lead vocals in the first two verse-chorus units of “Get Him Back!” are almost constantly doubled, spread to stereo left and right. But after the second chorus, at 1:58, we hear a breakdown featuring a single natural-sounding vocal in the middle of the stereo picture that engages in a call and response with backing vocalists (Rodrigo herself doubled). These backing vocals sing “I want to get him back, then I want to get him back,” a line derived from the start of previous choruses. This chant-like repetition can be heard as a fragmentation of those choruses, similar in some respects to the fragmentation in prechoruses discussed by Summach (2011, 12). The repetition features alternation between two versions of material, a half step apart. The start of the chorus is repurposed here and deprived of its pitch variety, creating a sing-song alternation that could seemingly go on indefinitely while the texture gradually builds. Restricting the alternation to a half-step or whole step span in a repeating-phrase rebuild creates a sense of claustrophobic constriction that further increases tension. The gradual addition of increasingly intense percussive elements and of a new countermelody starting at 2:22 leads ultimately to a breakdown chorus featuring the backing vocals and an acoustic guitar. A repeating-phrase rebuild recalls gospel practices and resembles a vamp in a live performance, where a melodic snippet, supported by a loop, can be repeated indefinitely while the texture gradually builds.38 Repetition of a vocal line, like repetitive chant in a liminal ritual, can lead to mantra-like semantic satiation, with the listener hearing the text more as a sound than a carrier of linguistic meaning.39 Insistent repetition of a lyric can make the familiar seem strange, create abstract patterns that echo the use of repeating motifs in visual art, or appeal to a childlike pleasure in rhymes and chants (Negus and Astor 2015, 238–239).

The repeating-phrase rebuild, “a consistent combination of repetition and intensification,”40 is an approach that occurs as early as the Isley Brothers repeating “a little bit louder now” during the rebuild of “Shout” (1959), but has seemingly become increasingly common since 2010 (see Section 7 below; Table 10).41 The insistent repetition of text, melody, and rhythm in repeating-phrase rebuilds is a loosening technique that reflects the transitional nature of the section (Caplin 1998, 85). Such an approach contrasts with the more parsimonious use of material, with less literal repetition, that is characteristic of the more tight-knit melodies of classic vocal bridges, verses, prechoruses, and choruses. While verses and choruses often adopt a period, SRDC, or other phrase structure where repetition is combined with contrast (Nobile 2020, 39, 73), and prechoruses are often part of a larger SRDC structure encompassing verse and chorus (Summach 2011, 18–21), the repeating lines of rebuilds engage instead in insistent repetition. Insistent verbal repetition in a rebuild can act as a transition from the more lyrically diverse initial verse-chorus cycles of a song to a more verbally repetitive final third of the recording in which the chorus lyrics are the focus. Yet the arrival at the chorus perhaps most significantly provides relief from the relentlessly repeating line, often combining with an arrival on tonic and the return to a full texture to provide a satisfying sense of resolution.

6. Anacrustic Cues and Highpoint Delay

As the arrival is approached, both sounding events, in the form of big drum fills, wordless screams, or ascending glissandi, and quiet, in the form of caesuras or other breakdowns, can anticipate the end of the rebuild and the return to a full texture. These are “anacrustic cues” (Attas 2015, 281). Paradoxically, both of these apparently opposing strategies can be effective in making the landing point a satisfying one and can be pleasurable in themselves. Breakdowns at the ends of rebuilds can create highpoint delay and ambiguity as to the “true” moment of arrival.

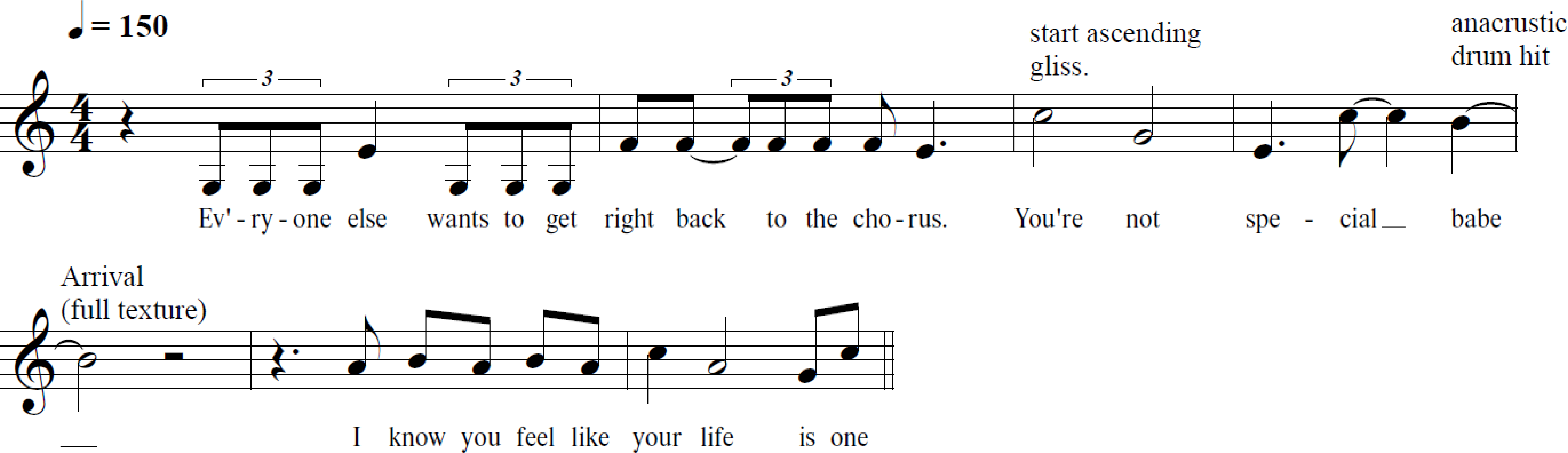

In Orla Gartland’s “You’re Not Special, Babe” (2021; Example 12), the lyrics explicitly forecast the arrival of the chorus and an ascending glissando acts anacrustically right before the arrival of the full texture. After a litany of sung comments about “everyone” (“Everyone lies, everyone cries …”) as the texture and tension gradually build with the help of a tresillo rhythm on a tom, the final statement of Gartland’s lead vocal self-consciously refers to the formal sectional arrival that is forthcoming— “Everyone else wants to get right back to the chorus.” The lyrics thus act anacrustically. When the chorus does finally arrive with the now-familiar text “You’re not special babe,” however, it is not accompanied by landing on tonic and a full texture. Instead, we hear Gartland accompanied only by an unearthly ascending synth glissando that, in combination with the dropout of all other elements, renders the vocal floating, untethered. Ascending pitches and especially upward glides such as this one are associated with high arousal, excitement, and building to a climax (Huron 2006, 323–324, 326). Ascending glissandi are also an example of a continuous change—by violating the usual bounds of equal temperament, they can contribute to a sense of disorientation as the arrival is approached.42 With a short but intense drum fill, the full texture returns on the third downbeat of the chorus at 2:44 and the listener finally receives sonic satisfaction.

The screams that in many cases occur near the ends of rebuilds (Table 11) are more dramatic, heightened forms of the anacrustic vocal cues at the ends of buildup introductions in songs like “I Heard it Through the Grapevine” (discussed by Attas 2015 at 281) or in prechoruses. Distinctions between the vocal utterances at the ends of buildup introductions or prechoruses and those near the ends of rebuilds reflect differences in how the passages function. Vocal “oohs” or grunts before the start of the first verse or before the arrival of the first chorus are almost completely anacrustic, providing a sneak preview of the lead vocal line that is about to be heard or of the forthcoming chorus. Screams, drum fills, or glissandi near the ends of rebuilds, however, can have both an anacrustic function—preparing the way for the return of the chorus at the arrival—as well as a climactic one. Screams, such as that in Maggie Rogers’s “Want Want” (2022) at 2:21, can be so intense that they themselves constitute a moment climax of greater import than the sectional climax that follows.43 As with Covach’s “dramatic AABA forms,” the highpoint of the song in many cases becomes a moment right before the return of previous material (2010, 9).44 Some of the screams in Table 11, like the one in “Want Want,” occur shortly before the arrival, while others, such as Roger Daltrey’s in “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” occur simultaneously with the moment of arrival. The former can be anacrustic and climactic, while the latter are primarily climactic but still may have anacrustic function as preparation for the return of more conventional singing.

In addition to anacrustic cues that generate excitement through loudness, lyrics, pitch increases, or glissandi, silence or a sudden reduction in texture can create anticipation for the return of a full texture (Attas 2015, 289; Table 12). Breakdowns or withholdings of the kick drum in EDM tend to occur in later metric or hypermetric positions, such as at the end of a measure or at the end of a four-measure or 16-measure segment (Butler 2006, 92). They thus have an anacrustic quality, building energy towards an arrival on the downbeat. Breakdowns and caesuras in the songs analyzed for this study tend to be similarly positioned. A breakdown and rebuild in a pop song act as a larger-scale anacrusis to the return of the chorus and outro, and a secondary breakdown at the end of a rebuild falls in a later hypermetric position within the larger rebuild. In Olivia Rodrigo’s “Good 4 U” (2021; Example 13), the breakdown and rebuild act as a structural anacrusis to the chorus and outro. Nested within that larger structure, there is a breakdown chorus at the end of the rebuild. Within that breakdown chorus, there is a short additional ending breakdown in which the instruments drop out and we hear just Rodrigo’s voice a cappella dramatically describing her ex as “like a damn sociopath.”45 These accumulating breakdowns on different structural levels increase the listener’s anticipation of the arrival ever further. Breakdowns at the starts of rebuilds and textural reductions at their conclusions also can provide relief from the near-constant loudness of much twenty-first-century compressed pop music, refreshing the listener’s ears for the final stretch of the song (Neal 2008, 303–304).

Anacrustic breakdowns at the ends of rebuilds, whether in the form of breakdown choruses, caesuras, or other reductions in texture, can be connected with discussions by Lee (2020, 2.5), Huron (2006, 325–326), Patty (2009, 329–330), and Summach (2011, 15) of highpoint delay, in which achievement of the highpoint is delayed either with a ritardando or with rests. In the verismo opera context that Lee discusses, there is often a slowing of tempo, creating suspense by making the listener wait longer. At the ends of rebuilds in pop songs, the tempo typically does not slow, but rests or textural reduction create a “sonic void” (Peres 2016, 85, 93–96) that intensifies the listener’s desire for an arrival that is also the awaited highpoint. With a breakdown chorus, the listener anticipates a return to the previously heard chorus with a full texture, but the song temporarily frustrates that expectation, as a deceptive cadence would harmonically. The arrival of a version of the chorus with a reduced texture can seem a kind of “failure”—it is the chorus the listener has been expecting, but a “flawed” version of it.46 The delay of a climax builds tension, increasing anticipation of the arrival and making it all the more satisfying when it arrives (Huron 2006, 315). Delaying an anticipated highpoint or resolution can create doubt and interest in jaded listeners who are otherwise certain that it will come, with the temporary withholding of full satisfaction becoming pleasurable (317). This stratagem is particularly effective when the listener has a strong expectation that a given event will ultimately occur (315). Highpoint delay can also create ambiguity as to where the true climax or arrival occurs.

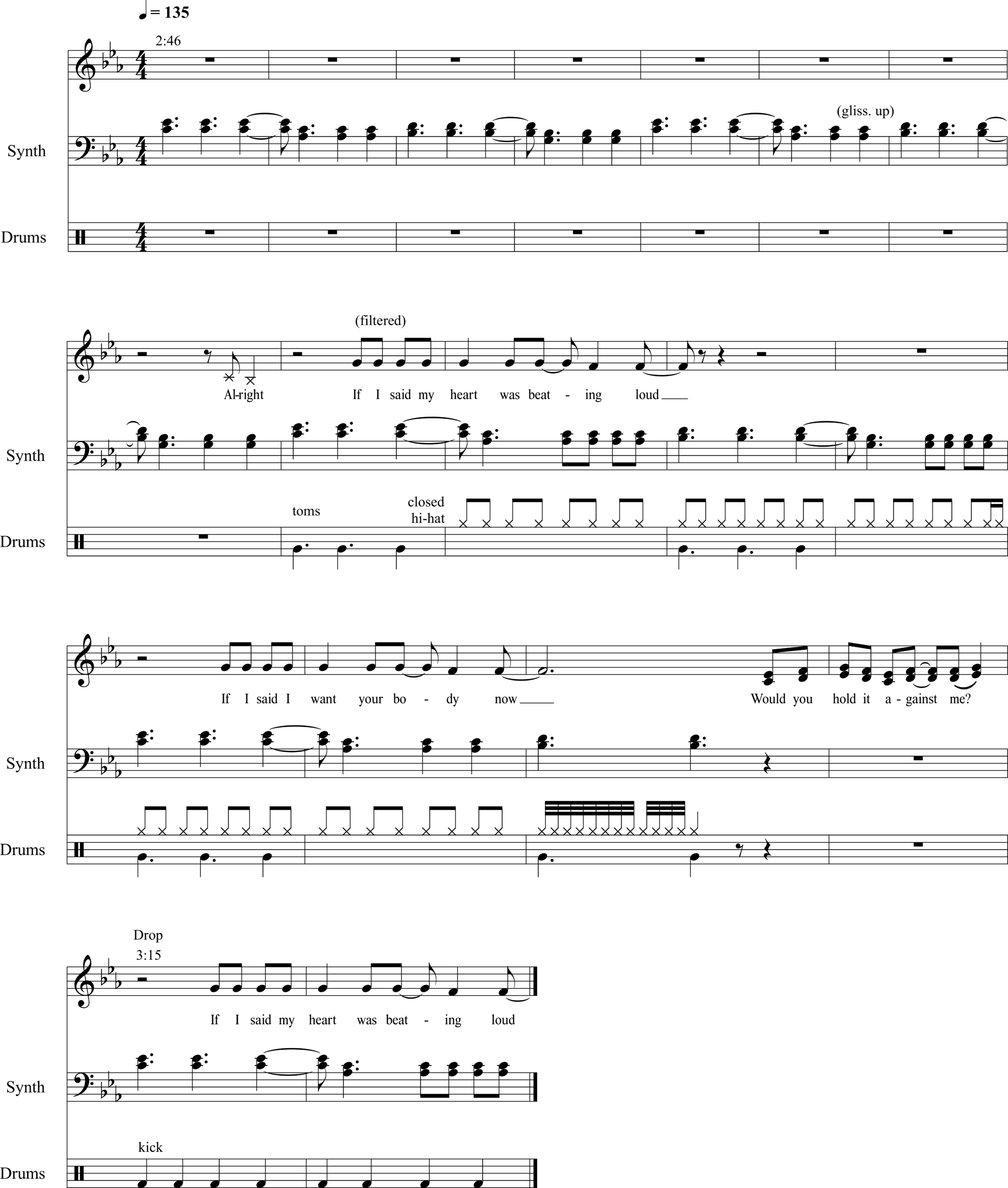

Britney Spears’s EDM-influenced “Hold It Against Me” (2011) contains another example of a breakdown chorus occurring at the end of a rebuild, delaying sonic satisfaction. It illustrates how primary and secondary parameters can have independent highpoints that create a disjunction between the syntactic and statistical climaxes. This can cause ambiguity and create challenges in deciding where the “arrival” actually occurs. Here, the breakdown and rebuild, starting at 2:09, initially feature an ascending synth glissando, a gradually opening filter, and Spears speaking rather than singing. The chordal loops of earlier in the song have been abandoned and replaced by a volatile, tonally chaotic space that disorients the listener. At 2:17 the pulse switches to a half-time dub-step groove, with glitching sounds and Spears shortly thereafter singing “Give me something good . . .” to a new melody. Rhythmic density rapidly increases in the snare, building to a new peak of tension at 2:45. Yet rather than an immediate return to the full chorus, the listener at 2:46 first hears the chorus loop harmonies in greatly reduced form as synth chords pulsating in a double tresillo pattern (Example 14). The arrival of the chorus loop harmonies after the tonal chaos that has preceded creates a satisfying sense of return, even as the lack of vocals and drums leaves the listener still unfulfilled and eagerly anticipating a full texture. The chorus vocals then return at 3:01, but heavily filtered. A final dropout occurs at 3:13, leaving Spears singing a cappella the song’s title “would you hold it against me?” When the full-textured version of the chorus with four-on-the floor kick comes immediately afterwards, it is all the more satisfying.

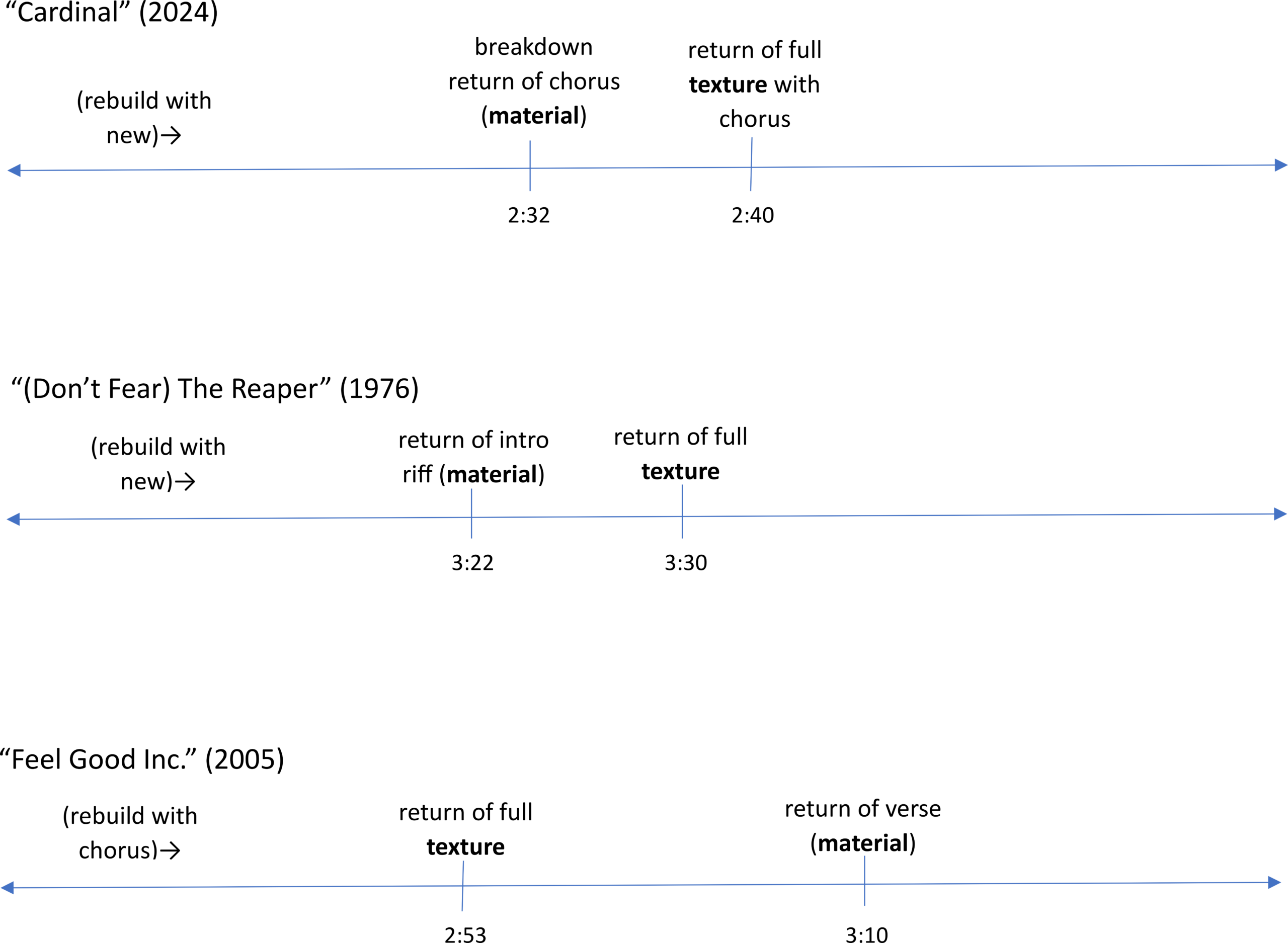

There are four possible spots that we can think of as being the “climax” or highpoint of the song. The earliest is at 2:45, when the increasingly dense snare pattern reaches peak intensity. This moment can be heard as the statistical highpoint because the rhythmic density is the highest. The next moment that could be considered the climax is the arrival of the pulsating double tresillo synth chords immediately following. This is a syntactic climax because there is a return of the chorus loop coming after contrasting, bridge-quality material. Yet in some important respects this moment might not be heard as the climax because of the greatly reduced texture. The third moment that could be considered the climax is Spears’s a cappella “would you hold it against me” at 3:13, sounding over a final dropout of texture before the arrival. The final arrival of the full texture with four-on-the-floor kick at 3:15 (the “drop”) is a fourth option because we finally hear the return of a full texture after a prolonged period with reduced forces. Such a moment is paradoxically both a resolution of built-up tension and a pinnacle of energy, a “decisive release of tension” or “forte-type abatement” (Agawu 2008, 61; Lee 2020, 2.7, 2.9). This return to a full texture at 3:15, designated as the “arrival” in my analysis of the song in Appendix Table 1, can be considered a combined statistical and syntactic climax—primarily statistical because of the full texture and the enhanced loudness associated with it, but also syntactic because of the return of the familiar full version of the chorus and a landing on tonic. The return of the chorus can also be heard as a sectional climax—where the climax is not a moment in time but rather a full section (Osborn 2010, 84).47 Because syntactic climaxes tend not to immediately dissipate their energy (Meyer 1989, 306; Meyer 1980, 194–195),48 in many cases they also constitute sectional climaxes. Breakdowns and rebuilds can effectively provide extra energy and power to the choruses that follow them (de Clercq 2012, 235), allowing the song to sustain an emotional high in its latter stages. Energy is maintained through the chorus and then sometimes upped even further in the outro, to create a euphoric feeling in the listener (Geary 2024, 4.18).49 In the case of “Hold It Against Me,” at 3:29 there is a closing further increase in energy as the chorus moves to its second half, with a new pulsating synth over the lyrics “’Cause you feel like paradise . . .” added to the already-full texture. Example 15 illustrates additional instances of disjunctions between the return of previous material and the return to a full texture, showing how the return of material can come first, as in “Cardinal” (Kacey Musgraves, 2024) and “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper,” (Blue Öyster Cult, 1976) or the return to a full texture can precede the recapitulation of previous material, as in “Feel Good Inc.” (Gorillaz, 2005). Regardless of whether the syntactic or statistical arrival comes first, these disjunctions create formal loosening and ambiguity for the listener as to the “true” moment of arrival.50

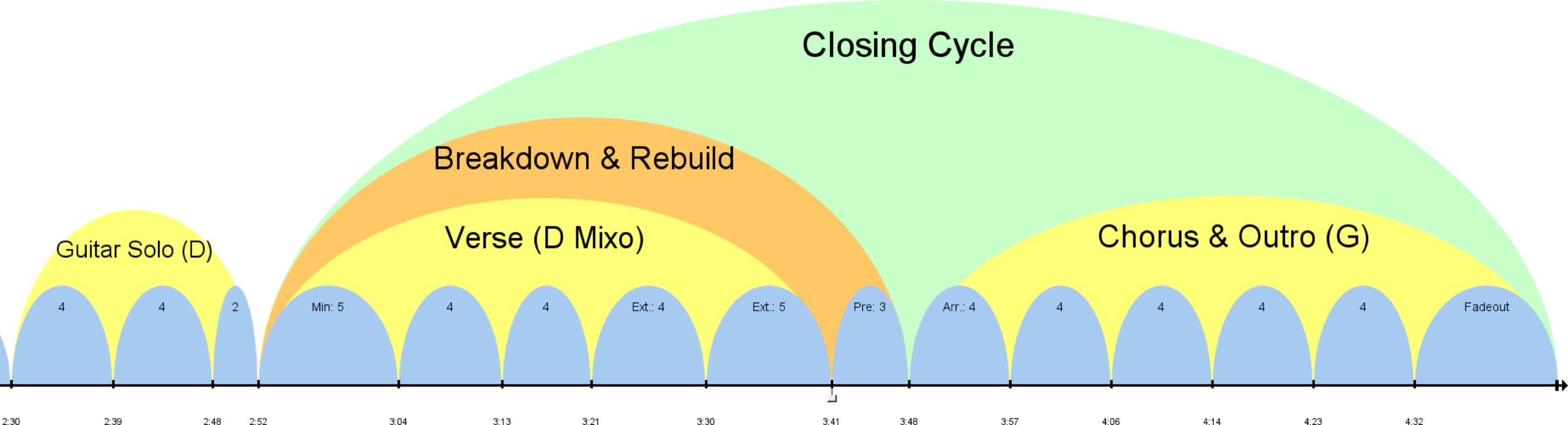

Hypermetric extension can also create highpoint delay. Rebuilds typically consist of four-measure segments, and the moment of arrival usually occurs after such a quadruple hypermeasure. Some songs disrupt this expectation and delay the arrival by adding measures unexpectedly, in a manner not unlike that discussed by Summach in reference to prechoruses (2011, 15). In Boston’s “More than a Feeling” (1976; Example 16), for example, hypermetric irregularity in the breakdown and rebuild create tension that is resolved by the hypermetric regularity of the arrival. The verse-based breakdown starts at 2:52 with a five-bar hypermeasure that dissipates the energy of the preceding D major guitar solo, but two regular four-bar hypermeasures follow as a D Mixolydian drumless verse/bridge blend rebuilds the texture. Then, unexpectedly, at 3:21 the end of the verse is extended with a new four-bar hypermeasure echoing the previous vocal line “she slipped away” as the electric guitar and drum kit return. This is followed by a five-bar hypermeasure starting at 3:30 that both disrupts the established hypermeter and delays the start of the prechorus, with lead vocalist Brad Delp reaching a dramatic new highpoint of G5 before the backbeat drum pattern is paused and replaced with a halting fill. The prechorus adds a third measure to the two measures of its previous iterations, further delaying the arrival. This prechorus concludes with a dominant harmony that resolves to the G major tonic of the chorus at 3:48. The four-measure hypermetric regularity of the chorus/outro reinforces the sense of stability arising from this arrival on tonic. As with a breakdown chorus, hypermetric extension teases the listener, pleasurably delaying arrival at the anticipated goal and making the ultimate achievement of that goal all the more satisfying.

7. Historical Change

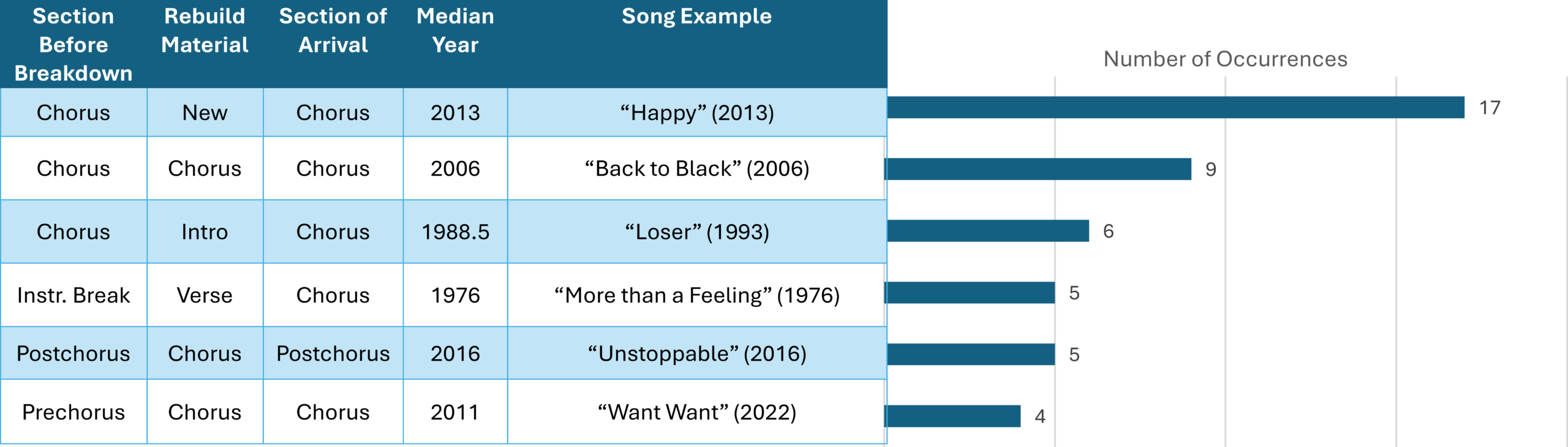

While the 118 recordings analyzed in this study are not sufficient to definitively determine historical trends with rebuilds in the time period of the sample, evaluation of the songs as a group suggests some changes during this span. In particular, rebuilds based on intro, verse, and instrumental material appear to have become less common, while the use of new material for rebuilds has increased. As part of this rise of the use of new material, the repeating-phrase rebuild has seemingly become a very common approach. These are tentative findings that could be confirmed in a future more systematic and expansive study, but they are consistent with broader trends in popular music identified by other scholars.

Introductions, verses, and instrumental breaks, which were fairly common rebuild partners prior to 1986, have since then seemingly become rare as the basis for rebuilds (Table 13).51 Introductions (1985), verses (1984.5), and instrumental breaks (1984) have the earliest median years of release of the middle rebuild partners among the songs analyzed. Prior to 2002 (dividing the 118 analyzed songs approximately in half by year of release), the middle rebuild partner was either an intro (typically instrumental) or instrumental break in 38 percent of the analyzed rebuild songs (23 out of 61). But from 2002 on, only five percent (three out of 57 analyzed songs) employed one of these two sections as a middle rebuild blend partner (p < .001 for a chi-square test of independence), and there are no analyzed examples later than the throwback soul band Alabama Shakes’s use of an instrumental rebuild in “Gimme All Your Love” in 2015. Prior to 2010, introductions were used as middle rebuild material in 24 percent of the analyzed songs, making them, after choruses, the second most common rebuild material source in analyzed songs dating from before that year. Yet among the 46 analyzed songs dating since 2010, not a single one uses introduction material in this role (comparing pre-2010 and 2010 on, p < .001).52 The apparent decline of rebuilds using intro material is consistent with scholarly findings that instrumental intros to songs themselves have become shorter since the mid-1980s (Klimmt et al. 2023, 1227 Fig. 2; Léveillé Gauvin 2018, 296): if there is no substantial introduction to the song, then there is no intro material on which to base the rebuild. The decline in the use of introductions as the basis of rebuilds among analyzed songs was accompanied by a reduction in the number of rebuilds constituting instrumental breaks or solos. Instrumental rebuilds such as those in Blue Öyster Cult’s “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” (1976), Fleetwood Mac’s “The Chain” (1977), and Don Henley’s “The Boys of Summer” (1984) seem to have mostly become a thing of the past.53 The twenty-first century rebuild appears to be primarily a vocal phenomenon.

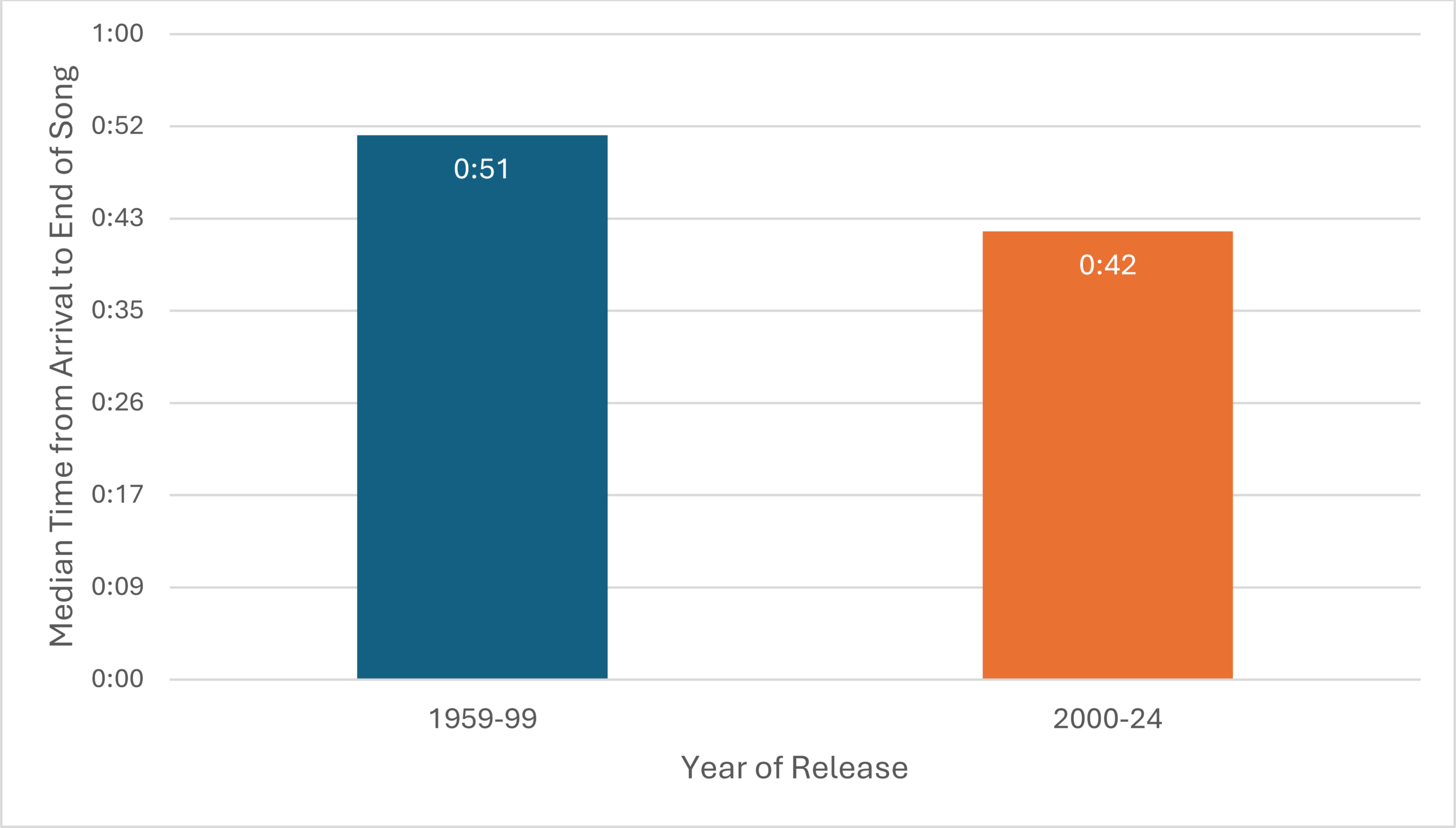

Using a verse as a rebuild partner is another option that was common in the 1960s and 1970s but that seems to have become less common. 28 percent of analyzed songs prior to 1980 used a verse as the middle rebuild partner (seven out of 25), while only 8 percent of analyzed songs dating from 1980 on did so (seven out of 93; p = .005). Examples from earlier decades of verses used for rebuilds include Them’s “Gloria” (1964), Boston’s “More than a Feeling” (1976), the Rolling Stones’ “Midnight Rambler” (1969), and the Stones’ “Shine a Light” (1972). A much later example that is a nostalgic throwback in other respects as well is R.E.M.’s “Man on the Moon” (1992). The decline in use of verses as rebuild material is consistent with Asaf Peres’s 2016 observation that third verses have become rare in general in mainstream pop (2016, 156).54 With the apparent decline of the use of intro, verse, or instrumental material for bridge-quality rebuilds, analyzed songs from 2000 on took substantially less time from the arrival to the end of the song (Figure 6; p = .028 for a two-sample t-test comparing the mean before 2000 with 2000 on; see Section 3 and Figure 5, above). Less time was needed to complete recordings because the rebuild material no longer demanded a reset of the verse-chorus teleological arc. The apparent decline in use of intro, verse, or instrumental material for rebuilds is thus consistent with the historical trend towards shorter songs between 1986 and 2020 found by Klimmt et al. (2023, 1229 Fig. 5; see also Tauberg 2018).

Using chorus material as the basis for a rebuild (creating a bridge-chorus blend) seems to have been relatively rare prior to 1986, with “Shout” (1959), “Live and Let Die” (1973), and “Serpentine Fire” (1977) among the few examples from this earlier period. In this earlier era, a chorus was used as the rebuild partner in only 13 percent of the analyzed songs (five out of 38). Yet in analyzed songs from 1986 on, choruses were the most frequent rebuild partners in cases where previous material is repurposed for a bridge blend, with 36 percent of the analyzed examples (p = .01 for a chi-square test of independence comparing pre-1986 with 1986 on). Since 2010, choruses have seemingly been rivaled or even superseded by new material as the most common rebuild partner, yet they continue to be a commonly used option (Table 13).

Analyzed rebuilds since 2010 most commonly have not repurposed previous material in the song but rather have used new material at their beginnings and cores, creating more of a “pure” bridge section rather than a blend. Prior to 2010, 21 percent of analyzed songs used new material as the middle rebuild option. But from 2010 on, new material has seemingly become the dominant approach for the middle rebuild partner, with exactly half of the analyzed songs since then using this approach (Table 13; p < .001 for a chi-square test of independence comparing pre-2010 percentage with 2010 on). As seen in Table 7 above, chorus-new-chorus is by far the most frequent sequence of sections before, during, and after a rebuild among analyzed songs, and the median year of release of the 20 analyzed recordings using this pattern is 2013. Relatively recent examples where new material is used throughout the rebuild include Turnstile’s “Holiday” (2021), Leon Bridges’s “River” (2015), and the New Pornographers’ “Backstairs” (2014). It has been almost as common in this most recent era, however, to use new material for the start and middle of the rebuild but to end with a breakdown chorus, as in “Hold It Against Me” (2011) and “Good 4 U” (2021). Breakdown choruses at the ends of rebuilds seemingly became common in the mid-1980s and have remained prevalent through the present day. As seen in Figure 7, among analyzed songs, the percentage using chorus material at the end of a rebuild leading into arrival on a chorus was significantly higher from 1986 on (eight percent prior to 1986 and 35 percent since; p = .002). This reflects the rise of breakdown choruses at the ends of rebuilds, which both act as a preview of the full-textured chorus and delay its arrival.

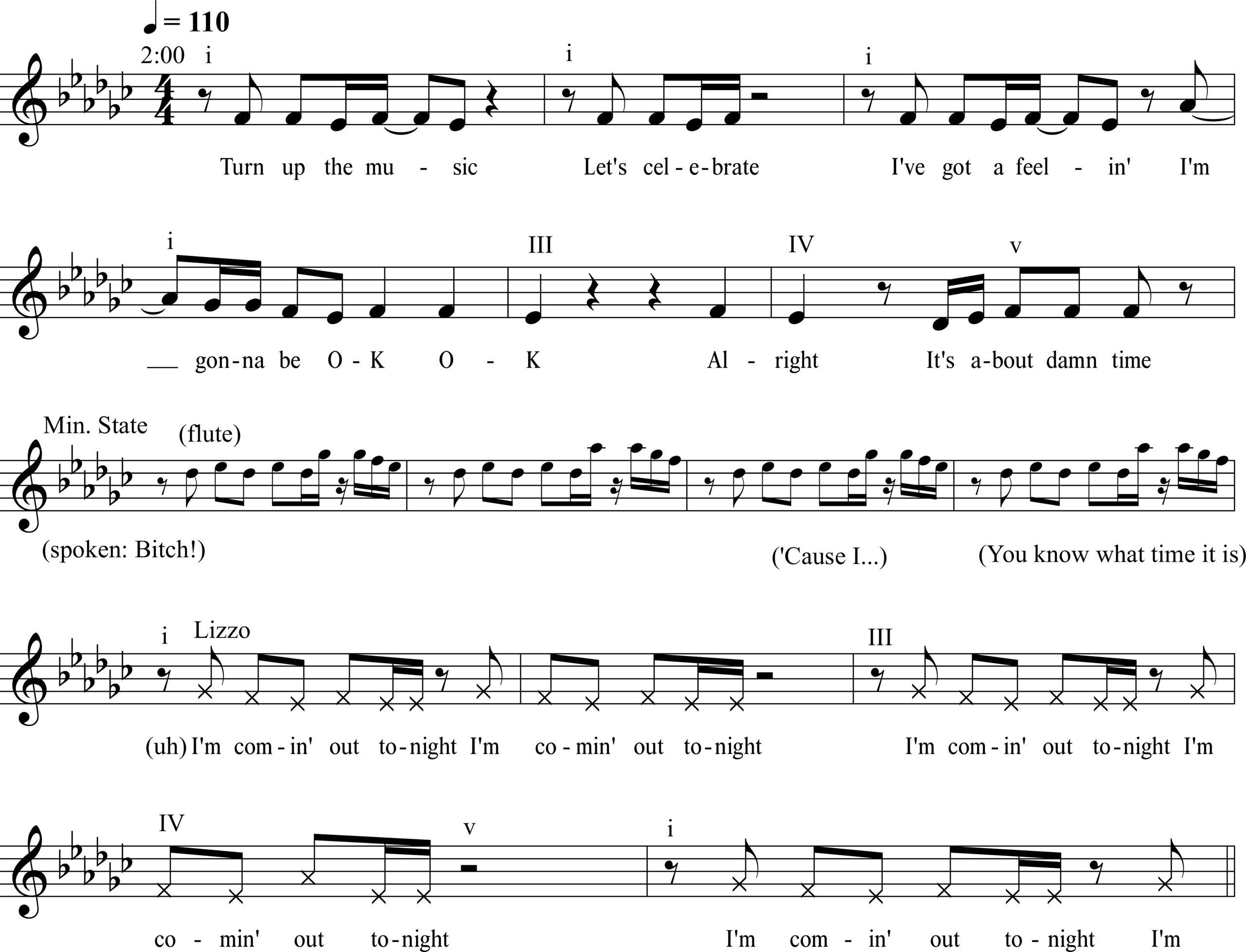

While using new material for the rebuild can potentially align with a traditional bridge’s approach of presenting melody and harmony that contrasts with the rest of the song, many rebuilds since 2010 do not create significant harmonic contrast and instead rely more on melodic and textural differentiation. This is consistent with the general trend in twenty-first century popular music away from harmonic variety, with most mainstream pop songs using only one or two harmonic loops for the entire recording (Peres 2016, 65).55 Analyzed rebuilds since 2010 using new material often employed the harmonic progression of the verse or chorus (or a slightly altered version of one of these, as in Lizzo’s “About Damn Time” (2022; Example 17)) as their harmonic basis, but have a new melody and the textural contrast of breakdown and rebuild. Increased reliance on one or two loops for an entire song might lead listeners to desire new material (in the form of a new melody) to complement textural contrast in rebuilds.

Analyzed rebuilds with new material since 2010 also typically lacked the combination of variation and contrast of phrases common in de Clercq’s classic or modern bridges or in the bridges of Tin Pan Alley. Antecedent-consequent or SRDC structures as rebuilds in this era are seemingly rare. Instead, the use of new material usually takes place as part of a repeating-phrase rebuild, with a single melodic line recurring over and over. Examples since 2010 include Rihanna’s “Only Girl (In the World)” (2010), “About Damn Time,” and the backing vocalists’ insistent repetition of “fly” and “high” in the Black Pumas’ “More Than a Love Song” (2023; Table 14). Rather than the tight-knit phrase structures of older rebuilds using verse material, such as those in the Beatles’ “Help” (1965) or R.E.M.’s “Man on the Moon” (1992), there is vamp-like repetition of a phrase over a loop. These repeating lines do not have the same kind of narrative function that verses and choruses can have—there is even less verbal variety than is typical for choruses. Repeating-phrase rebuilds occurred in many if not most instances of analyzed rebuilds using new material going back to the 1960s (such as in the Four Tops’ “I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch)” (1965) and the Jackson 5’s “I Want You Back” (1969)), but this approach has seemingly become more common since 2010.

This increase in use of new material—melody in particular—for a rebuild is apparently at odds with the contentions of Peres and Osborn that twenty-first-century EDM-influenced pop songs do not present new material in a bridge but instead recycle previous material while presenting it in a texturally-reduced form (Peres 2016, 148; Osborn 2023, 47–49). One might explain this discrepancy by noting that I analyzed numerous post-2009 songs that would not be considered “Top-40 EDM.” But EDM-influenced analyzed post-2009 songs that contain new melodic material in the breakdown and/or rebuild include Rihanna’s “Only Girl (In the World)” (2010), Katy Perry’s “Last Friday Night (T.G.I.F.)” (2010), Britney Spears’s “Hold It Against Me” (2011), Marshmello and Bastille’s “Happier” (2019), and Ed Sheeran’s “Bad Habits” (2022). Thus the use of new material for a rebuild is seemingly a common option even in songs strongly influenced by EDM. As with other tentative observations about changes over time in the approach to rebuilds, future research may provide more conclusive evidence.

Conclusion

In this article I have examined an aspect of popular song that has been addressed in passing by other scholars but that has not previously received focused attention. Breakdowns create a liminal space in which rebuilds can occur. Unlike the buildup introductions that have previously been dissected in scholarly literature, rebuilds—even those using new material—interact in a dialogue with previous content in the recording, both its intro and the verse-chorus cycles that typically follow it. Both primary and (especially) secondary parameters can contribute to increasing tension in a rebuild in either a terraced or continuous fashion, and anacrustic cues can prepare the listener for arrival at a full texture. Breakdowns at the conclusions of rebuilds create anticipation but also can teasingly delay the arrival. The use of rebuilds in popular music has seemingly changed over time, with instrumental rebuilds apparently having become rare and repeating-phrase rebuilds using new material becoming more prevalent.

While most pop songs do not have a rebuild as defined here, the collection of recordings analyzed for this article shows that there are numerous examples of them in multiple eras of popular music, with many of them representing major pop hits. Rebuilds are of particular interest because they are frequently a site of blended formal roles, because of their potential to create dramatic highpoints in song, and because they show that discussions of teleology in popular music should extend beyond attention to core verse-prechorus-chorus cycles. Bridges have tended to be underexamined both because of their usually transitional nature and because of the misperception that they belong primarily to an older tradition of popular music. Yet the examples analyzed for this essay—many of them from the last 10 years—show that bridges continue to be crucial elements of popular song and at times the central focus of a recording. This article is a first step in bringing renewed attention to the teleology of bridges and looks forward to further scholarship in this area.

Thank you to Stephen Hudson, Olivia Mather, Alexis Cantelme, and to the anonymous peer reviewers for their help in developing this article.

References

Adams, Kyle. 2019. “Musical Texture and Formal Instability in Post-Millennial Popular Music: Two Case Studies.” Intégral 33: 33–45.

Agawu, Kofi. 1984. “Structural ‘Highpoints’ in Schumann’s Dichterliebe.” Music Analysis 3 (2): 159–180.

—————. 2008. Music as Discourse. New York: Oxford University Press.

Attas, Robin. 2015. “Form as Process: The Buildup Introduction in Popular Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 37 (2): 275–296.

Barna, Alyssa. 2020. “The Dance Chorus in Recent Top-40 Music.” SMT-V 6.4. https://doi.org/10.30535/smtv.6.4.

Baur, Steven. 2020. “‘And the Drummer, He’s So Shattered . . .’: The Percussive Core of Beggars Banquet.” In Beggars Banquet and the Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Revolution, edited by Russell Reising, 26–40. New York: Routledge.

Biamonte, Nicole. 2014. “Formal Functions of Metric Dissonance in Rock Music.” Music Theory Online 20 (2).

—————. 2018. “Rhythmic Functions in Pop-Rock Music.” In The Routledge Companion to Popular Music Analysis: Expanding Approaches, edited by Ciro Scotto, Kenneth M. Smith, and John Brackett, 190–206. New York: Routledge.

Butler, Mark Jonathan. 2006. Unlocking the Groove: Rhythm, Meter, and Musical Design in Electronic Dance Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Byron, Tim, and Jadey O’Regan. 2022. Hooks in Popular Music. New York: Springer Nature.

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. New York: Oxford University Press.

—————. 2004. “The Classical Cadence: Conceptions and Misconceptions.” Journal of American Musicological Society 57 (1): 51–118.

—————. 2024. Cadence: A Study of Closure in Tonal Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Carter, David S. 2021. “Generic Norms, Irony, and Authenticity in the AABA Songs of the Rolling Stones, 1963–1971.” Music Theory Online 27 (4).

Covach, John. 2009. What’s That Sound?: An Introduction to Rock and Its History. 2nd ed. W. W. Norton.

—————. 2010. “Leiber and Stoller, the Coasters, and the ‘Dramatic AABA’ Form.” In Sounding Out Pop: Analytical Essays in Popular Music, edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach, 1–17. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

de Clercq, Trevor. 2012. “Sections and Successions in Successful Songs: A Prototype Approach to Form in Rock Music.” Ph.D. diss., Eastman School of Music.

—————. 2017. “Embracing Ambiguity in the Analysis of Form in Pop/Rock Music, 1982–1991.” Music Theory Online 23 (3).

Duinker, Ben. 2020. “Song Form and the Mainstreaming of Hip-Hop Music.” Current Musicology 107: 93–135.

Endrinal, Christopher. 2011. “Burning Bridges: Defining the Interverse in the Music of U2.” Music Theory Online 17 (3).

Ensign, Jeffrey S. 2015. “Form in Popular Song, 1990–2009.” Ph.D. diss., University of North Texas.

Fink, Robert. 2011. “Goal-Directed Soul? Analyzing Rhythmic Teleology in African American Popular Music.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 64 (1): 179–238.

Geary, David. 2024. “Formal Functions of Drum Patterns in Post-Millennial Pop Songs, 2012–2021.” Music Theory Online 30 (2).

Gossett, Philip. 1979. “The Overtures of Rossini.” 19th-Century Music 3 (1): 3–31.

Hannan, Calder. 2022. “Structural Density and Clarity, Technical Death Metal, and Anomalous’s ‘Ohmnivalent.’” Music Theory Online 28 (1).

Hepokoski, James, and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. New York: Oxford University Press.

Huron, David. 1992. “The Ramp Archetype and the Maintenance of Passive Auditory Attention.” Music Perception 10 (1): 83–91.

—————. 2006. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

James, Robin. 2015. Resilience and Melancholy: Pop Music, Feminism, Neoliberalism. Alresford: Zer0 Books.

Klimmt, Christoph, Mareike Sperzel, Jasmin Straßburger, Viviane Winkler, Yannick Schneeweiß, and Hubert Léveillé Gauvin. 2023. “Catering to the Impatient Digital Listener: Accelerated Composition Patterns in Popular Music, 1986–2020.” Convergence 30 (3): 1219–1235.

Lavengood, Megan. 2021. “‘Oops!… I Did It Again’: The Complement Chorus in Britney Spears, The Backstreet Boys, and *NSYNC.” SMT-V 7.6. https://vimeo.com/societymusictheory/smtv076.

Lee, Ji Yeon. 2020. “Climax Building in Verismo Opera: Archetype and Variants.” Music Theory Online 26 (2).

Léveillé Gauvin, Hubert. 2018. “Drawing Listener Attention in Popular Music: Testing Five Musical Features Arising from the Theory of Attention Economy.” Musicae Scientiae 22 (3): 291–304.

Martin, Nathan John. 2024. “Corpus Studies and ‘Close Listening.’” Music Analysis 43 (2): 191–246.